A love letter to the majestic beauty and lifegiving powers of the ocean world (Pembrokeshire, South West Wales, and sailing the North, North Atlantic, Mediterranean, Celtic, Caribbean seas; mid-2010s to present): If it only takes 120 minutes a week for humans to feel the benefits of being in Nature, what does that tell us about Welsh-born Hannah Stowe who says, “There was never a time when I did not know the sea”?

For Stowe, who grew up in a “cottage by the sea,” enveloped on three sides by the waters of St. Bride’s Bay that empties into the Celtic Sea and the English Channel, she found “solace,” “energy,” and “always felt safe.”

By Manfred Heyde [CC BY-SA 3.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

Tucked away on a secluded tip of the southwestern coast of Wales, lulled by a “lullaby” of “gentle worlds,” Hannah Stowe learned to swim when she learned to walk. Fascinated by “celestial light” and the “beacon, of Strumble Head Lighthouse,” she climbed treetops to get better views of the seascape, bicycled to the rocky beaches where she explored coves, tidal pools, eyed sea birds, seals, dolphins, snorkeled, surfed, and became “obsessed” with walking the Pembrokeshire Coastal Path, considered one of the most beautiful walking paths in the world.

For Stowe, this meant “there was a current inside me” “as natural and as essential as the act of breathing.”

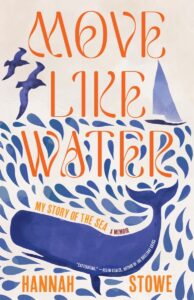

For us, it means Move Like Water: My Story of the Sea is a captivating, coming-of-age story of a sea observer, navigator, researcher who became a marine biologist offering us an authentic voice for the sea. It also means you’ll be treated to some of the most exquisite nature writing, awakening and refreshing us to ocean worlds we may get glimpses of but haven’t experienced in the immersive, intensive way Stowe has.

Stowe’s story highlights the growing body of research and a movement called Ecopsychology, which provides scientific evidence on the connections between our physical and mental health. Transporting us to how she’s felt and what she’s learned over her twenty-something years “being out there in the elements” that “creates an entirely different state of mind.”

More expansively, the memoir makes the case for how our health is affected by the health of our waters, Stowe having witnessed the human impact of commercial exploitation and climate change on the health of the marine animals who depend on them.

A story that’s painted with vivid imagery by an author who, like her mother, is also a painter. Each chapter is introduced presumably by one of Stowe’s charcoal sketches of the animals you’ll learn about. If it weren’t for the beauty of the prose, you could almost tell this story through images. Then again, if it weren’t for enchanted prose those images would not be painted for you at all or as deeply.

By “Malte Uhl (User:Zzzip)”derivative work: Snowmanradio [CC BY-SA 2.5]

via Wikimedia Commons

That’s why there’s six chapters named for seabirds and sea mammals – giant, large, and small: Fire Crow (the Cornish Chough), Sperm Whale, Wandering Albatross, Humpback Whale, Shearwater, and Barnacles.

Only one chapter, Humans, veers dramatically different, although the lure of the sea is fundamental to Stowe’s recovery, healing. Riding a wave bigger than she could tackle, she suffered a serious accident, leaving her in excruciating nerve pain, two surgeries, and a lifetime of adjusting to knowing her limits when they seemed limitless. In spite of it all, when Stowe could get out of bed she returned to her university science studies and later bought her first sailboat she aptly renamed Brave.

By The Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk

[CC BY-ND 2.0] via Flickr

If you’ve been raised as a city slicker, you might find Stowe’s remote UK homeplace terribly lonely rather the sustenance she derives from natural landscapes with endless horizons and stunning wildlife, including sightings of majestic sea creatures and discovering smaller delights.

There’s too many seabirds to list. To give you a sense of an impressive one, here’s a description of the Manx Shearwater:

“Elegant of wing, making a long gliding journey north from South America, up the eastern seaboard, following the Gulf Stream, to take up residence in burrow nests on Skomer, Ramsey, and Skokholm” (islands in Wales where the world’s majority breed).

By Hugh Venables [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The memoir, then, is a mix of the personal with the science, ecology, history, and the living, breeding, birthing, nurturing conditions of an amazing winged creature known for its ability to migrate thousands of miles from their homes.

Stowe’s prose is vibrant, tingling with an itch to explore seas around the world beyond the “western edge of Britain, the edge of my world.” Even if you’re not a sailor, you’ll relate to how “bonds form quickly at sea, when “you are trusting each other [sailmate(s)] with your life.”

The first ocean going vessel discussed is the Valiant 40, a research vessel Stowe volunteered to assist on led by Professor Hal Whitehead, a global expert on cetaceans – whales, dolphins, porpoises. Meeting his then doctoral student Laura Feyrer inspired her career direction. Now we see the author as a strong feminist voice rising above male-dominated traditions when it comes to the sea who had to “work twice as hard for half the opportunity. You prove everything, and prove it ten times again.” Loved the irony when Stowe points out boats are named after women!

It was on this expedition that Stowe, manning the deck in the dark of the night, “felt a deep presence” of an “ocean giant.” Awe, in hearing a sperm whale’s eerie whale songs. “The loudest single animal in the ocean” shows us the importance of sounds, not just sightings.

The whale is a persuasive example of environmental activism making a huge difference as these giants almost became extinct in Antarctica in the mid-sixties. Boycotts, quotas, bans, and legislation made it illegal to kill whales for commercial reasons, though a few countries still do.

By 3HEADEDDOG [CC BY-SA 3.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

Stowe’s captivating journey continues to enlighten and carry us to other sea creatures, such as the Wandering Albatross, a “bird of legend” known for the “mastery of its force” flying through fierce winds, requiring both parents to switch turns to care for their young.

And then, “Sometimes, something is just beautiful. You don’t know why, it just is, and the world is better for the fact that it exists,” Stowe writes. The literary world is better for her story of the sea. She hopes, so will the health and future of the seas.

Lorraine