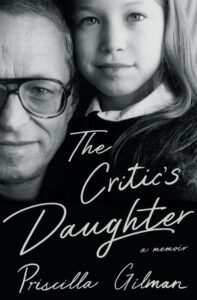

Bravo performance by a virtuoso drama critic’s daughter who played the role of selfless Daddy’s Girl (Manhattan and Connecticut, 1970 – 2018): “Since Daddy left, it seems anything is possible,” writes Priscilla Gilman, who “wished and wished on stars when it came to her father”: brilliant and troubled Richard Gilman, famed dramatic and literary arts “philosopher-critic”; Yale Drama School professor for thirty years; and author of seven books.

“I lost my father for the first time when I was ten years old. In the months and years that followed, I lost him over and over, many times and in many different ways. This book is my attempt to find him,” she explains about the complex man she adored more than anyone else in her world.

Honoring and protecting his legacy while staying true to his conviction that without truth there’s no art a delicate balance she pulls off in grand style, though it took her six years after her father’s death in 2006 to begin a performance of a lifetime. You can’t help but be bowled over by her unwavering devotion to him.

How to navigate treacherous waters when “loyalty is at stake”? Not just to her father, but to her mother: Lynn Nesbit, powerhouse literary agent co-founding Janklow & Nesbit Associates, with a client list a mile long – Joan Didion, Anne Rice, Michael Korda, Michael Crichton, Tom Wolfe, John Le Carre, Henry Louis Gates Jr. (See the full list.)

The sense you get is the drama “enthusiast” for “authenticity” would be melodramatically applauding the authenticity of this exquisitely composed memoir. Well-balancing the “joy and tears” of her profound attachment to a “living, wounded soul” with a “hunger for a larger life.”

Richard Gilman comes through as larger-than-life. Priscilla as selflessness beyond measure – no matter the sacrifices she made to perform the role she’d “been assigned at a very young age”: calmer-in-chief, happy warrior, peacekeeper.

“Without my father, would anyone truly know who I was?” is an interesting question, given the dutiful role she played even when anguished and not being truthful. Ironic for a man who believed the “highest forms of love demands rigorous honesty.” Professionally, yes, but not when it came to his needy, emotional roller-coaster self.

You might assume the commonality between a mother and father’s passion for literature were ingredients for a thriving marriage, yet they divorced when the author was ten. Not then, or afterwards, pretty. The repercussions of a family falling apart are palpable. Excruciatingly devastating for those who couldn’t bear it. Richard Gilman cries, sobs, pleads whereas Lynn Nesbit is a picture of strength, with a “lets-get-on-with-it” attitude.” She seems to have kept the family together until she couldn’t, which the author never forgets.

Richard Gilman could play child as equally well as scholar. A “passionate believer” who “believed in childhood,” he could be so much fun. An avid sports fan too, so the author became one nestled beside him. Nesbit was mostly out-of-the-picture working. Closest with Claire, the author’s slightly younger sister, a “girly girl.” Carrie, the nanny, is credited as a “beacon of stability for us all.”

Nesbit felt Priscilla was “obsessive” about her dad. Her reply implies, how could I not be? “He “made me the thinker, writer, parent, human that I am”? Performing with “preternatural sensitivity,” grace, self-control, and selflessness for her Daddy throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood may have suited her well but it seems mother knows best about the consequences she’d pay. Literature, if nothing else, teaches that.

A stark contrast is shown between a nurturer of the careers of writers yet not seen during their marriage. A “fierce advocate of authors” philosophically pitted against a man renowned as a “ruthless arbiter of their worth.”

Of Claire, the author’s best friend, she says, “Other than my father, there was no one I loved more.” You wince wondering how Nesbit reacted to those words. Like the “cool realist” she’s attributed to here? You’ll appreciate the author’s appreciation of her mother, but that comes much later.

The Critic’s Daughter is a candid assessment of enmeshment between a without-boundaries father-daughter bond. Almost fused together, raising questions on when the line is crossed by a parent too dependent on a child? The child on the parent?

The memoir is both a primer on the role of playfulness and the devastation of divorce. Saturated with adoring love, the book is also a beautiful testament to the emotional power of literature and the performance arts. Priscilla Gilman loves performing and singing, but directed by both parents to pursue an academic life. Achieving notably as an English literature professor at Yale and Vassar, where she was tenured. (Surprisingly, her father wasn’t; at Yale; no doctoral degree). After he died, she gave academia up. The last part of the memoir explains why the courageous change of heart. Brave having received an elite education all her life, she’d attended one of the most prestigious all-girls private schools in the country, the Brearley School, founded in 1884. The alumnae list another Who’s Who. My favorite, Caroline Kennedy.

Growing up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan near Central Park and Museum Mile was a privileged life, with the burdens and sacrifices offstage. In one of the eye-popping statements, a precious excerpt from the author’s diary, is a list titled, “Things Not to Do When I’m w/Daddy.” First up is “Don’t Cry.” Followed by “Don’t Complain,” “Don’t Be Difficult,” “Don’t Tell Him Anything But Good News,” “Don’t Mention Mommy,” and “Don’t Expect Him to Be the Daddy of Old.” Penned in middle school, it’s stunning and sad that this young girl could be so mature and perceptive of the role she had to play, shaping who she became. How did she manage all that, in light of all that happened?

Claire was the troublemaker constantly aggravating her father as a child; Priscilla, the “easy one,” the “good girl.” The only one of his three children – Nicky, loving son and artist from his first marriage – Richard Gilman knew would unconditionally always give him what he needed. (He loved them all.) Vividly, we see a “little girl who was enraptured by her father’s magical abilities, recognized his vulnerability and addictive tendencies, and feared his inevitable demise.”

Happiness and despair, trust and betrayal, halcyon and tumultuous, are intertwined. As if you can’t have glorious without paying the price.

Richard Gilman’s books include Chekhov’s Plays: An Opening into Eternity; The Making of Modern Drama; and his hot-button memoir Faith, Sex, Mystery (this review by Mary Gordon cited), which exposed his conversion from Judaism to Catholicism and his loss of faith, along with his struggles reconciling an existential “romantic soul” with his lust for sexual transgressions, erotic tendencies, gender experimentation.

Considering how much this family read, including to each other, quotes from great literature and poetry are richly infused. Relishing is the roster of writers like Bernard Malamud (Uncle Bern), Toni Morrison (Aunt Toni), Ann Beattie (Aunt Ann), Susan Sontag, and a slew of other writers, playwrights, and students who frequented the Gilman Manhattan home and countryside retreat in Connecticut.

Opening with a Shakespearean quote, “All the World’s a Stage,” befits the man who felt “great plays can be as revelatory of human existence as novels and poems.” Daddy’s Girl turns in a stellar performance like being judged on a stage getting a standing ovation.

Lorraine