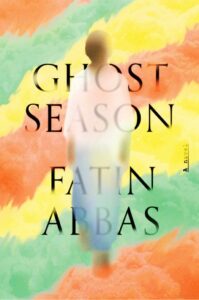

A character-driven novel illuminates the complexities of a humanitarian crisis and a love story in the poorest country in the world, hoping for peace but rarely seeing it (South Sudan on the border with north Sudan; November 2001 to August 2002): Ghost Season is a must-read.

Especially if you want to better understand why Sudan, independent from Britain since 1956, and South Sudan split from the north in 2011, have been at or close to war for nearly all those years. And why South Sudan, where the novel is set, the poorest country in the world — #167 out of 167! — and one of the most diverse ethnically, culturally, and religiously hasn’t been able to achieve a lasting cease-fire.

via Wikimedia Commons

“What fiction gives you that journalism can’t is this emotional, visceral experience of living things through characters you care about. That can give you a different understanding,” said Fatin Abbas in an interview about her deeply absorbing, affecting, enlightening historical novel.

Reading Ghost Season when the newest cease-fire in Sudan didn’t last; when thousands have already been added to the already millions of refugees; and evacuations by other countries rescuing their citizens is taking place, pulls you in with immense authenticity.

Ghost Season arrived when the humanitarian crisis in South Sudan couldn’t have been worse. Now it is. We can’t even begin to imagine what 9 million people in a country of 12 million have and are going through. Glazing over numbers on that monumental scale, Abbas knows living amidst a few, diverse people up-close helps us comprehend the enormity.

Ghost Season is about relationships. Relationships that form and change when people from different walks of life and experiences come together. Their voices are vehicles for grasping South Sudan’s long story of struggles and conflicts. Vivid, through exquisite prose. Lyrical. Nimble, equally authentic from the tender to the fierce. Gentle at an unhurried pace shifting to terrorizing and fast-moving.

It wasn’t until the end of Part I (of seven parts) that I came up for air to google Abbas’ background to try to figure out how she could equally put us into such contradictory scenes as if we were there, observing both. Just like one of her female characters, schooled in “observational photography.” (See Dena below.)

Turns out Abbas was born in Sudan, raised in Khartoum, the capital, spending the first eight years of her life there. The last without her scholarly father, an English professor, jailed, deemed a political enemy. When he was released, the family fled to America and became US citizens. So what drove a young woman, before she became an award-winning scholar known for her non-fiction Sudanese commentary (and more, see https://www.fatinabbas.com/), to return to Sudan to work for an NGO humanitarian organization? The place her novel revolves around. Still, to finely pull off the transition from academic to emotional perceptiveness in harsh environments that test people calls for an entirely different skill set. Differences abound everywhere.

Optimism to make a difference is at the center of the goodwill of Ghost Season. Set at a compound of an unnamed NGO humanitarian organization in the South Kordofan region at the international borders of southern Sudan and South Sudan. The NGO’s logo features palms in prayer, a familiar symbol of peace, embracing others with similar missions.

South Sudan separated from the Muslim-controlled government in Khartoum that adheres to Arabic traditions in a hopeful move towards democracy. Predominately Christian, the new country follows African traditions, comprised of sixty-four tribes, mostly people of Nilote ethnicity who speak different languages.

Labeling significantly oversimplifies the diversity of challenges and what’s at stake in South Sudan. A landscape of dwindling natural resources spectacularly affected by: 1) geography and climate, the overwhelming dry and wet seasons; 2) desert and semi-arid landscapes, also grasslands and swamplands (the Sudd cited, https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6276/); 3) the irony of impoverished people in a country of rich resources (such as oil, Chinese workers in the novel’s background; gold in the news since that’s what Russia is after to fund the Ukraine War; and 4) climate change severely degrading already grim conditions. How else to explain a flooding river disappearing in three months, shocking another character in the story? (See Alex below). Climate change depicted as ground zero should shake the world.

via Wikimedia Commons

via Wikimedia Commons

All these issues – poverty and the desperate need for humanitarian aid; access to clean water; Sudanese Arab nomad cattle herdsmen and farmers resettling to South Sudan competing for the same resources as the Nilotes, pitting black against black, all represented by the five characters Abbas has dreamed up with clear-sightedness.

The first chapter introduces the characters so you won’t get confused or forget who they are, their differences, and roles. No one knew each other at the start; intimately they know one another by the end:

ALEX: Surveyor and Mapmaker. White, the only one. From the US. His job is to identify “villages, cattle migration routes, water wells, and grazing pastures” since the current maps are fifty years old. Seems to be the one to take charge of the compound, but at twenty-seven he’s too disoriented, fearful, and tense to be able to. Unbearable, sizzling heat contributes to his daze.

WILLIAM: Translator. Catholic, a “Nilot man” even though he’s returned from Sudan educated. Better off because he’s working at the NGO compared to others treated as-less-than, slave-like. Thirty-three, elegantly dressed and proud, he takes on what Alex cannot.

MUSTAFA: Hardworking “errand boy.” The poorest. A street-smart, twelve-year-old kid, willing to do all the unpleasant chores and whatever else, for money. Attached to William.

DENA: Cinematographer, unsure of what she’s filming. Born and raised in Sudan, her family fled to Boston. She’s returned for unsaid reasons that drive Alex nuts. The unfolding story shows her what to record.

LAYLA: Cook. Arabic nomad from Sudan, she nurtures everyone. The love story between William and Layla sets up intense drama. The most endearing relationship, as William patiently woos Layla for as long as he can, acutely aware that her heart isn’t supposed to accept his love. Their future on edge, uncertain, like everything else.

Of the female characters, you’ll love Layla from the start but the same can’t be said of Dena. Closed-off, she’s not at all receptive to Alex’s friendliness, though she warms to Layla and is intrigued by Mustafa. Fearless and low-key, whereas Alex isn’t the laid-back type. Who can blame him here? Plenty of obstacles, while Dena is free-floating hiding behind her camera. There’s a feminist focus in terms of conventional Layla compared to unconventional Dena, and how women bear the crushing burdens fending for their children and themselves. So many widows, victims of heinous wars.

For William and Layla: how long can two forbidden people manage to keep their love? For Mustafa: how long can someone in dire poverty stay out of trouble? For Alex: how long can an American aid worker remain in a place he has no idea “how he was to find his bearings?” For Dena: how long can someone stay closed-off when their life is threatened?

For us: in spite of a deeply personal connection, a scholar’s insight, stirring prose, we still ask: how Fatin Abbas pulled off this powerful heartwarming and heart-wrenching debut novel?

Lorraine