Foxy storytelling: transforming foxes into humans and what that says about us (Northern China, Qing dynasty, also Japan; 1908 – pre-1911 when China became a Republic): “I’ve always been fascinated by old Chinese tales of fox women (and men) who tempt and beguile humans,” notes Yangsze Choo in her bewitching novel, “The Fox Wife.”

Foxes are “charming tricksters.” Prepare, then, to meet a most graceful and cunning character – Choo’s mythical Snow who claims she’s a fox capable of “shape-shifting.” Appearing as an exquisite narrator concealing her true self. A twenty-three-year-old “foxy lady” who effortlessly shifts between her animal and human forms when she’s out for revenge. Animals and humans seen bearing deep wounds of grief. By page four, you’ll know the cause of Snow’s wrath.

Set in Northern China, the “ancestral home of the “fox cult,” The Fox Wife opens in 1908, at the end of China’s last dynasty, this one ruled by Manchuria. Snow flees her home named Hu, or Fox in Chinese, located in the Manchurian grasslands, with the mindset of a fox hunting her prey yet appearing as a lovely, delicate young woman pursuing a Manchurian photographer who killed her child. Interestingly, this historical time dovetails with the “the new art of photography” that had reached this remote part of the world.

by Damiano Luchetti [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

by Jonathen Pie https://unsplash.com/@r3dmax [CC0] via Wikimedia Commons

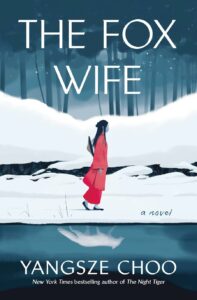

The deception starts with the elegant cover. Our attention is drawn to the beauty of a young woman, too lightly-clothed in a Manchu-style dress called “changyi,” wearing dainty shoes walking in the snow. Already we’re charmed and tricked! You can stare at this image many times and not notice her mirrored reflection of a rare white fox, seen mostly in frigid, northern landscapes.

Malaysian-born Choo of Chinese ancestry is fascinated with the Chinese culture’s “fox spirits.” She wraps a fox’s story with a detective’s: sixty-three-year-old Bao investigating the killer of an alluring “courtesan” found frozen on the doorstep of a restaurant in the “wealthy and fashionable” city of Mukden, once Manchuria’s capital. Today, it’s the Chinese city named Shenyang, and the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Mukden Palace.

by xiquinhosilva [CC BY 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

Bao, though, wasn’t one of the well-to-do. Perhaps he could have been. Seen wrestling with how his life might have turned out differently had he not sighted a rare black fox when he was seven, along with his young female companion. An arrangement his mother made to soothe his grief when she suddenly banished his nanny. The two made a “fox shrine,” theirs built from bamboo and its leaves. Then one day she too disappeared. He says he’s never been the same. Both Snow and Bao carry their sorrow, though his is buried deeper, quieter. It will surface in unexpected ways in this twisty tale dominated by foxes – animals and fox-like human beings – and those like Bao who believe foxes condemn, curse. “Foxes make our living beguiling people.”

Snow’s and Bao’s alternating storylines are exceptionally well-crafted. Intentionally designed so the ending of one connects to the beginning of the other. Connections become clearer, eventually merging. Which makes for some unique historical, mythological, and mysterious literary craft steeped in Chinese culture, folklore, and secrets. Magnetically and cleverly so, because foxes are used as a metaphor for the complexities, disparities, and duplicity of humans.

Literary-wise, one of the novel’s intrigues is why Snow’s voice is told in the first person whereas Bao’s is relayed in the third?

Ancient Confucian philosophy may be one reason. Symbolized by the Yin and Yang black-and-white circle of darkness and lightness, representing opposite traits and energies, the life force or “qi,” considered essential to balancing all living creatures. Foxes, like humans, “lie in between darkness and light.”

Interestingly, two characters’ names mean white and black, indicative of the importance of names Choo points out in her illuminating notes.

For Choo, everything has a purpose. Maybe the difference in narrative styles is due to Bao’s belief the black fox caused his shadow to be fading, disappearing. Troubled by what could foretell his impending mortality while foxes can be “immortal”? Or, since he’s more discreet compared to foxes who “can’t help but sticking our noses into everything,” Snow has more energy, passion, and fearlessness so she reveals more? Or, for a long time Bao “can’t puzzle things out,” while Snow is confident she can?

Revolution is in the air. First in the aftermath of the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War cited, when Snow is well-served by speaking many languages including Japanese. Becoming a maid for an “Elder Mistress,” widow of the first master of a legendary medicine shop, who asks her to also be her confidante listening in and translating private conversations between her beloved grandson Bohai (son of the current owners) and his Japanese friends. Fits since Snow is a rather curious creature who can’t help eavesdropping, a lot. Her relationship with her mistress makes her far more human than she cares to be since foxes cannot afford to let their guard down, or appear weak.

You’ll also read of revolutionaries, who bookend the historical period of the novel before the Chinese Revolution of 1911 ended empires, when China became a Republic until it was overthrown by the Communist Party in 1949.

Above all that transpires and you learn, The Fox Wife is foremost about the many forms of Love. Love lost, due to the death of a child. Forbidden love between a young boy and the playmate he never forgot. Love in marriage, and the lack of love in arranged ones. Love questioned in the ancient practice of polygamy when the patriarch had many wives, mistress(es), and concubine(s). (Their differences complicated by status and treatment, royalty or wealthy, see here). Love ran away from, yet feelings resurfaced. Familial love between multiple generations of families living together.

This artful novel also tackles loneliness from the standpoint of the actions all creatures take, man and animals, so they’re not as alone. Snow and Bao are terribly lonely, concealing their feelings when they set out on their journeys. Other characters as well, emerging as good and evil.

Morality heightened in a scene discussing the “Thousand-Year Journey,” or “righteous living.” Choo explains it as a “spiritual pilgrimage that probably has roots in a mixture of Daoist, Buddhist, and folklore traditions” for achieving “enlightenment.” Foxes and humans aspire to that lofty notion, though differently.

Choo acknowledges she was concerned “nobody would want to read a book written from the point of view of a fox.” How utterly, wondrously untrue.

Physically, the novel is also special in its printed format. Published with extra-wide margins that ease reading (and a reviewer’s note-taking). This, too, not by accident. “Marginilia,” Choo notes, is “an old Chinese literary tradition.” Aimed at encouraging women access to literature in China’s traditionally male-dominated society when they were excluded from “literary salons.” A 1000-year-old Chinese practice.

Beyond the myths, Bao’s fox sighting leaves him with an unusual ability to tell lies from truths. How useful for a detective, and for today’s world!

Lorraine