Why a scandalous early-20th century British family spawned a cottage industry still thriving (Cotswolds, England, Paris, and Spain; 1920s to 1939): I’m a latecomer to the “Mitford Industry.” A pet phrase coined by one of the six Mitford sisters, Jessica nicknamed Decca, fifth youngest. A “defiantly radical author and journalist,” says British literary biographer Selina Hastings in her introduction to Hons and Rebels, which reflects how Jessica Mitford’s breakout rebellious autobiography reads.

Originally published in 1960, reproduced in this handsome, limited edition by Slightly Foxed, a London bookshop and publisher I had the pleasure of stumbling upon during pandemic armchair browsing.

Decca intended the epithet to be disdainful of her landed gentry “eccentric” family, headed by 2nd Baron and Lady Redesdale, dubbed Farve and Muv. Nicknames and capitalizing phrases with a mocking tone abound. Sometimes playful, witty, though mostly in the early sections growing up in an “old and quaint” small village, Swinbrook, in “Cotswold country,” in the British countryside outside of London. A large family, including a brother Tom nicknamed Tuddemy, and those who served the “Ruling Class,” governesses who didn’t last long and a long-time Nanny, all living in a Downton-esque estate, Asthall Manor in the county of Oxfordshire, minus the charm.

By Vieve Forward [CC BY-SA 2.0] via Wikimedia Commons

The creamy-yellow stone that makes the Cotswolds a tourist destination is not the cozy image of the homes in the area nor in Jessica’s eyes. “It has the “look of frankly institutional architecture,” she says of the manor, resembling a “private lunatic asylum.” For many of the real characters who dwell inside – the Mitford parents and four of the sisters depicted, it’s a rather “eccentric” place.

Starting with rigid rules and boundaries. All the sisters were kept cloistered as they weren’t allowed to attend school outside the manor, only adored Tom was. (He boarded at Eton and then fought in WWII in Burma, so he’s mostly out of the picture. He died young, after the book ends). They weren’t allowed to have friends, only within their own kind – cousins, aunts, and uncles. Jessica the most distressed about missing the intellectual stimulation of teachers and yearning for friends and people from different walks of life. Isolation seems a root cause for why most of the sisters’ ideologies ran wild.

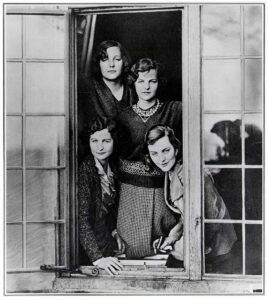

Which is to say I came to this autobiography without any knowledge of many of the family’s far-right extremist political ideologies ripe for an historic time. Unity and Deborah were Nazi supporters; Unity, the more viscerally disturbing of the two, had a close relationship with Hitler. Nor did I know that Diana was married to Sir Oswald Mosley, a staunch anti-Semite who led a British Fascist movement of “blackshirts” sounding similar to Hitler’s brownshirts. A Fascist too, along with both parents. Nor did I know Jessica was a Communist. Only two sisters come off as you might assume, loving the life of the British countryside: Pamela and Deborah/Debo, the youngest, who became the Duchess of Devonshire.

From The Sketch magazine, 1932

Via Wikimedia Commons

Decca wasn’t the best known of the infamous Mitford sisters. That distinction goes to socialite and oldest sister Nancy. She even said that: “In England, the name Mitford is no doubt associated in most people’s minds with my sister Nancy’s novels and biographies.” (Her novels include Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate.)

To get a sense for the Mitford industry thriving today, recent novels include The Mitford Murders series by Jessica Fellowes (2018 to 2023), comprising six mysteries, one for each sister in order of eldest; The Mayfair Bookshop: A Novel of Nancy Mitford and the Pursuit of Happiness by Eliza Knight (2022); and The Bookseller’s Secret: A Novel of Nancy Mitford and WWII by Michelle Gable (2021). There’s no shortage of non-fiction books about the Mitfords over the last twenty years either, such as a recent one published in 2017, The Six: The Lives of the Mitford Sisters.

But it’s Hons and Rebels that’s written in the first person, in an astute literary voice. Often, Decca feels like an observer looking in rather than a participant, which seems to mirror how she was growing up in a crowd of older sisters. “It never occurred to me to be happy with my lot,” she confides. Perceptively, at least by the time she was thirteen, she understood that someday she’d need a “Running Away Account.” That day comes and is central to the rest of her memoir when she meets Esmond Romilly, Churchill’s nephew, at nineteen, causing quite an uproar.

While the first part – what it was like to be one of the Mitford daughters of aristocratic, aloof parents so restricted and isolated – is essential to understanding the origin of Jessica’s “confrontational reputation” (Selina Hastings’ words), much of the rest revolves around her running-away-life with Esmond, known for his far-left working class political ideology, which matched hers. A risk taker, he was a Loyalist during the Spanish Civil War, which Jessica’s story takes us to.

Unlike some of her other sisters, Decca didn’t fit the mold of the exalted coming-out debutante season at seventeen, here too, revolting against the aristocratic class’s lifestyle and values. The coming-out tradition, the fashion and the glamour, was something her mother cared about.

Foolhardy in investments, the family was land rich and cash poor. Not interested in much, her father was a member of the Conservative Party and the House of Lords, though rarely went to London to participate. Her mother wasn’t much better, not too involved in child-caring other than issuing ultimatums and critiques of her children’s behavior but gets credit for being charity-minded – London’s poverty her cause. Jessica was deeply affected seeing the dire conditions of the poor and the working-class, which explains her early attraction to communist propaganda.

Esmond occupies Jessica’s heart and ideological soul. After their story ends in 1939 when the book ends, she comes to America and champions civil rights and the abuses of capitalism.

History is very much part of this picture, with a special disgust for former Prime Minister Chamberlain and his doomed appeasement policy towards Hitler. Winston Churchill succeeds him, one of a number of historic figures cited, such as JFK and the owners of the Washington Post Eugene/Agnes Myer and their daughter Katherine Graham.

The most poetic lines may be Jessica’s brutal assessment of her family. How they lacked the “qualities of patience, forbearance, and natural self-discipline that the worker brings to his struggle for a better life, the instinctive respect for the fundamental dignity of every human being.” You can’t help but admire her support for “humanity, peace and freedom.”

Postscript: For the past seventy-five years, Slightly Foxed has published a delightful quarterly literary magazine that bears the bookshop’s name. The artful covers drew me in, each by a different artist. A Slightly Foxed Podcast series accompanies the magazine. Hons and Rebels is one of their publications from their Slightly Foxed Editions. Charming British racing green hardbacks, with gold lettering and numbering on the spine and a red-ribbon marker. (Their Plain Foxed Editions are a lovely shade of “duck-egg blue.”) I’d forgotten what it felt like to hold a book so comfortably in one hand. It lends to reading a classic like this eye-opening one.

Lorraine