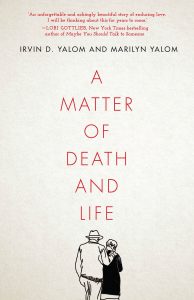

Life-affirming, love at first sight (Palo Alto, California; April 2019 – March 2020): Do you believe in love at first sight? Enduring love until death do us part? “Few regrets” in life? If you do, this book is for you. If you don’t, this book is for you.

Expect to be teary-eyed while wrapped in a comforting blanket as two distinguished professors and prolific authors candidly offer “two minds rather than one” as they look back on sixty-five years of a joyful, caring marriage and overflowing, rewarding lives until one is diagnosed with multiple myeloma (“cancer of the plasma cells”) and the other overwrought about losing the “most important person in my life.” One fearing so much of his past will be lost as his soul-mate was at the heart of it all, while also experiencing disturbing memory issues. All triggering “obsessional thinking” and “traumatic repression.”

Unthinkable it would seem for a man who devoted sixty years to psychological healing with devotees all around the world. A pioneering existential psychotherapist who treated countless bereaved clients now fears living as an “independent adult” for the first time in his life. Faced with the “inevitability of death” not unlike all of us when you strip the meaning of life down to its core. “How do we live meaningfully until the very end?” Two graceful people also ask in graceful prose, “How can we gracefully leave this world to the next generation?”

That man is Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry at Stanford University, Dr. Irvin Yalom. That woman was Dr. Marilyn Yalom, who also had an immense reach and resonance as a Stanford professor of French language, literature, and culture, and a feminist pioneer in women’s studies. Trailblazers in their respective fields.

With four children and eight great-grandchildren, a tight-knit, supportive family, plus an endless list of admirers – students, colleagues, researchers, readers – it’s hard to imagine more loving, fulfilling, good, and generous lives. Their last year together is remarkably life-affirming as each lived with few regrets. Each, though, taking a different perspective on how long to hold on for the other when your dignity is being chipped away with intolerable physical pain and hope dimming by the day.

Among the many themes packed into this short, provocative memoir (222 pages, including two beautiful photos and the poignant cover sketch) is the thorny topic of choosing when to die if it’s legal in your state. California is one of the states that has passed compassionate physician-assistant death with dignity laws, the word suicide rejected.

By a twist of fate, Irvin Yalom is supremely qualified to write about this as he’s known for his ability to counsel through “difficult dialogue.” Including baring his personal feelings, considered part of why he’s been so successful in changing lives. You’ll find Marilyn Yalom equally capable and frank, coming across as more practical-minded compared to his existentialist thinking and struggles with “death anxiety.” Both painfully honest in sharing their “torrent of pain”: hers more physical, his more psychic. Both philosophical as they document the worst year of their lives. She calmer and accepting, he more fearful and denying. Both grateful for all their blessings.

Which explains the emphasis in the title of death before life. And yet, above all else this intimate memoir is a wondrous celebration of two lives, and the grief that comes when their journey together is ending. “Mourning is the price we pay to have the courage to love,” the opening epigraph, speaks to all of us about “living meaningfully.”

“Evanescence” is a lovely word appearing in the title of one of Irvin Yalom’s chapters. It embraces a love story kindled when a fifteen-year-old boy fell in love with a girl about his age in ninth grade. That man is now 88; Marilyn was 87.

If you haven’t had a reason to become acquainted with Irvin Yalom’s psychotherapeutic work, you may have read one of his “teaching novels.” Spanning forty years, from 1974 to 2015, they include Every Day Gets a Little Closer; Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy; When Nietzsche Wept; Lying on the Couch; Momma and the Meaning of Life; The Schopenhauer Cure; I’m Calling the Police! A Tale of Regression and Recovery; The Spinoza Problem; and Creatures of the Day (https://www.yalom.com/books).

I was personally influenced by Yalom’s landmark textbook, The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, as a graduate student at the George Washington University in Washington, DC, where they both were born and raised. (The influence of their East European Jewish parents described with wonderful introspection.) I still recall the third edition’s purple cover and circles at the bottom for its surprisingly eloquent prose for a text, the bible in my group counseling course. The jacket colors have changed over the years; multi-colored with circles everywhere for the sixth edition co-written with Dr. Molyn Leszcz, President of the American Counseling Association, while Irvin Yalom was also writing this memoir.

In the forty-minute TED talk below, How a Life Shape’s a Life’s Work, Leszcz shares the stage with his forty-year old friend and collaborator, an “iconic figure” who “inspired generations of group therapists” on the “human condition.”

It’s “rare for a psychiatric text” to stay in print for so long, says Jeffrey Berman, an English Professor at SUNY Albany who wrote the only book that’s examined the full body of Yalom’s writings, Writing the Talking Cure: Irvin D. Yalom and the Literature of Psychotherapy.

Marilyn Yalom matches her husband’s compassion and slew of admirers, inundated with so many wanting to visit her during this precious time. Having to pace herself not to overtax how much she can extend of herself while she’s in wretched pain and dying.

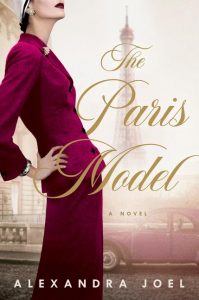

She too has a long list of published books, including Before the Chess Queen; How the French Invented Love; A History of the Wife; The Social Sex: A History of Female Friendship; The History of the Breast; and The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love released in 2018 (myalom.com). She too was committed to another writing project while writing this memoir: Innocent Witnesses: Childhood Memories of WWII, with an introduction by bestselling author Meg Waite Clayton, whose WWII novel, The Last Train to London was reviewed here: https://enchantedprose.com/the-last-train-to-london/. One of their sons, Ben, finished it. (Yes, planning to read it.)

To glimpse Marilyn’s presence, eloquence, and knowledge watch her give a fourteen-minute TED talk on How the Heart Became a Symbol of Love:

That’s what this memoir is: a symbol of love.

In commenting on an art exhibit that recently opened at the New Museum in NYC on Grievance in Art and Mourning in America, Washington Post art critic Sebastian Smee asks, “How do you translate mourning into community?” That too is what this memoir is about.

It’s not only a gift for us but for a profoundly grieving widower who discovers the hours he spends completing the memoir over four months brought him solace. Recounting it’s only “120 steps” from his Palo Alto home flooded with memories to his office, he still finds happiness while writing. Marilyn knew he would because writing the memoir together was her idea.

Lorraine