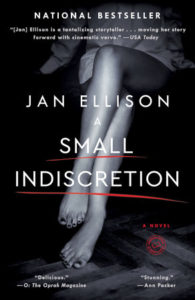

The Legacy of Self-Destructive Behavior (San Francisco, CA 2012; London, Paris, Ireland 1989): “What happens to a marriage?” Do we marry out of a “great capacity for love, or only great greediness and need”? When does love ebb into “habit”? When does a transgression cross the line for forgiveness? Above are some questions Jan Ellison pushes in her seductive debut novel, A Small Indiscretion. Small in the title among the deceptions, as the themes tackled are anything but.

The Legacy of Self-Destructive Behavior (San Francisco, CA 2012; London, Paris, Ireland 1989): “What happens to a marriage?” Do we marry out of a “great capacity for love, or only great greediness and need”? When does love ebb into “habit”? When does a transgression cross the line for forgiveness? Above are some questions Jan Ellison pushes in her seductive debut novel, A Small Indiscretion. Small in the title among the deceptions, as the themes tackled are anything but.

Tuck this factoid away as you rip through the pages: Ellison won an O’ Henry Prize for her very first short story. So as she cunningly unwinds what she calls the “threads” of her confessional story, written as a letter to her 21-year-old son, Robbie, who is in a medically induced coma after a serious car accident, even when you think you’ve got things figured out, you’re in for … well, an O’ Henry ending.

Does this classify as mystery genre vs. suspense? Literary fiction vs. commercial? These distinctions are fuzzy to me. Pin me down, I’d hedge my bets. Tag it literary suspense. The prose is exceptionally good and provocative, bridging literary and commercial. Named a “Best of 2015” by the San Francisco Chronicle (newly released in trade paperback), it’s the most psychologically suspenseful, literary novel I’ve blogged about.

Don’t you love it when a novel grabs you at the opening sentence? “London, the year I turned twenty” is the kick-off and then page 109 circles back to: “In London, I turned twenty.” The author artfully moves back and forth in time, tying a sordid “archaeological period” to a respectable present, connecting a tempestuous “sad past” to what seemed to be a stable, happy married life until Robbie’s accident:

“Where does the thread begin for you?” writes Annie Black to Robbie. “Where does it begin for your father? When did his seamless happiness begin to unravel?”

Annie asks these boldfaced questions at 41, but the entangled answers necessitate delving back two decades when she was working in London. The author worked in London too when she was Annie’s age; she took notes that inspired a novel penned years later. All Annie has is her memory and 13 beguiling poems (“moonlight and whispers”) she’s saved in a hatbox and not forgotten. So she wonders, as we might, about her veracity colored by time and shame. Yet she shares plenty of painful regrets and immoral admissions about her “self-indulgence,” egged on by her dependence on alcohol to let loose so she could feel confident and beautiful thus loved. (“If I am not beautiful, how can I be loved?”)

In a short, unnamed historical prologue, we’re introduced to an insecure Annie who buys bright, cheap gauzy scarfs to look “arty or sophisticated” at the London Victoria underground station, near where she’s living. She’s having an affair with her married boss, Malcolm Church, an engineer twice her age. His wife Louise is fragile and temperamental; their 10-year-old daughter, Daisy, is away at boarding school. The son of Malcolm’s friend, Patrick Ardghal, a photographer from Dublin, is living in a cottage behind their home. Annie is also having an affair with Patrick. It’s Patrick who writes those lovely, enigmatic poems and lives in the moment. The two men couldn’t be more different. Patrick’s stylish. His is a “thrown-together elegance,” whereas Malcolm is what-you-see-what-you-get, old-fangled. Annie’s drawn to the older man, I think, as the father figure (an alcoholic) who abandoned her; the other arouses her artsy side. Both inflame a nerve aching to be carefree. Who will know? She’s so far away from home. All that in five pages.

Chapter One opens with another hook: “It’s not always wise to assume that just because the surface of the world appears undisturbed, life is where you left it.” It’s September 5, 2011, a date chosen I suspect to tell us something very bad is about to happen. Indeed it does.

A photo of Malcolm, Louise, Annie, and Patrick at the White Cliffs of Dover before they boarded a ferry to Paris to spend a momentous Christmas together (not the kind of romantic Paris you may be envisioning) has arrived for Annie, jolting her present world. Who sent it? Why now? It’s an arresting photo given the hidden web of the foursome and an exposure technique called “solarization,” Patrick is known to have used. It creates “dissonance,” further highlighting the internal strife Annie already saw.

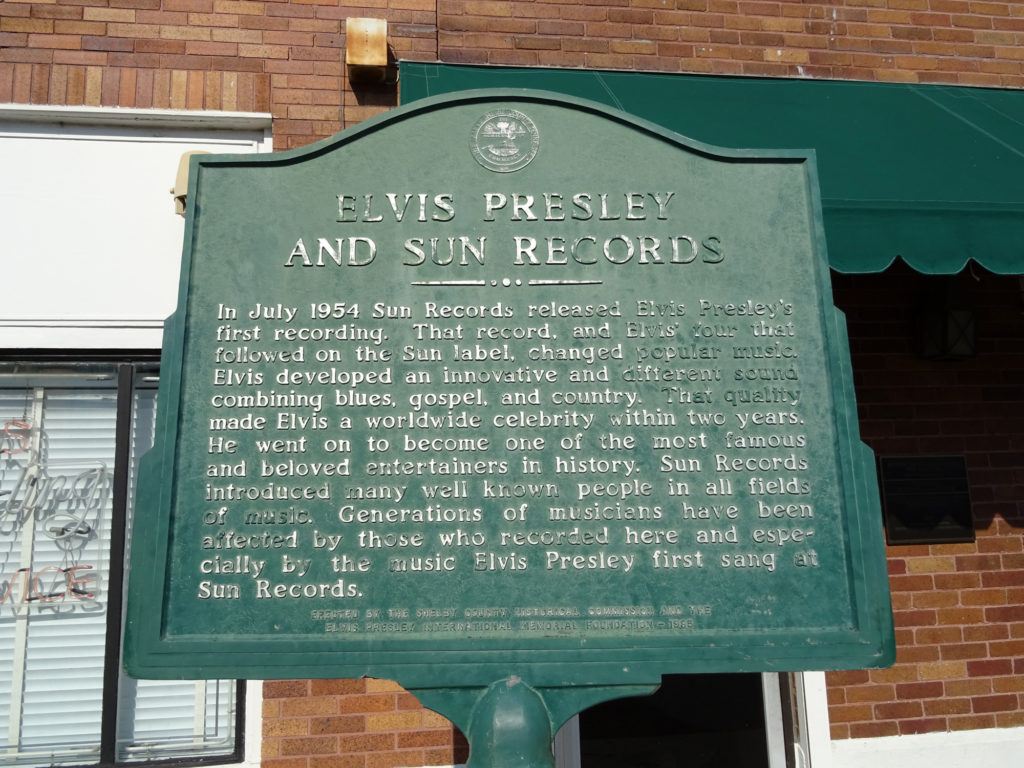

Port of Dover

By Nessy-Pic (Own Work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Including, sadly, her own. Four days before Robbie’s accident, Annie confessed to her husband Jonathan about the so-called “small indiscretion.” You’ll have to guess what that might be and when it happened. Not the ideal time to find the couple thrown together, more like camped out together, at the paradoxically named Mermaid Inn, near the hospital poor Robbie lies in, while Annie’s estranged parents nobly unite to care for their younger daughters, Polly, 6, and Clara, 9.

Jonathan Gunnlaugsson is also Irish, like Patrick. They met on a different ferry crossing the Irish Sea when Annie fled Paris. Something happened in Paris you’ll learn of in due course. Imagine, though, fleeing two relationships and then rapidly falling into another one. She and Jonathan travel together – Nepal and India – until Annie has news that causes them to abort the trip. Soon after, old-fashioned doctor Jonathan who grew up on a farm in Wisconsin proposes to Annie, launching her transformation into a sober, good adult.

That’s when Part I, Annie’s selfish, worrying-about-me period, ends. Part II still shifts back to that unstable era but now its heart is motherhood, selfless and worrying, especially about Robbie, understandably. Robbie has so much promise: a science scholar from Northwestern University doing an optical computing internship at Berkeley, headed to Japan’s National Institute of Information and Communications Technology when tragedy struck.

One of the consequences of the accident is medical proof Jonathan’s not his father. Robbie, if he pulls through, doesn’t know that. Who is his father? Malcolm? Patrick? Ellison drives home there’s no “escaping without consequence.”

One “thread” woven into Annie’s character is her artsy-ness. For the past fourteen years, she’s the proud owner of an offbeat lighting business in San Francisco, Salvaged Light, recycling old fixtures and then turning them into “one-of-a-kind” treasures. An older couple that managed the store has left; soon a new tenant, Emme Greatrex, occupies the upstairs loft, convincing Annie to let her work in the store in exchange for reduced rent.

Emme is a bit of a mystery. She’s blond and model-like, a bohemian type who dresses in cowboy boots and gold fishnet tights. A flirt, as in flirted with Robbie. As in she was driving that fateful car; escaped unscathed and then disappeared.

We don’t dwell on Emme’s miraculous fate. We’re glued to Robbie’s crisis and the enormity of reverberating effects. What happens to Robbie? What happens to his parents’ marriage? What happens to all the threads that have come undone?

Light is another authorial thread. Robbie’s interested in “light sources.” Annie’s business centers on light. Will Robbie see the light of his parentage? When does the reader see the light? Ah, remember that O’ Henry ending.

Lorraine