Inside the creative genius of a kinetic sculpture artist who lived life to the fullest (Indiana and other Midwestern states, New York, California, Scotland, England, France, Germany, the Netherlands; 1913-2002): How can an artist live nearly a century and leave his public mark throughout the US and Europe and no one has written about his life?

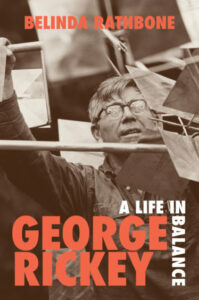

“Behind every public sculpture is a story the public never hears” says Belinda Rathbone opening her outstanding book about an American artist whose work can be seen everywhere if you know where to look. George Rickey evolved from a painter who loved history to become the most prominent moving sculpture artist outside of Alexander Calder. Initially inspired by Calder’s famous mobiles, he pioneered a technically more complicated “movement movement.”

“His sculpture, always an expression of balance and tension, uneven structures and counterweights at play with one another, also expressed, though he never said so, the dual forces of his personality and personal relationships in abstract form.”

To compare the work of two kinetic sculpture artists, here’s two looks at Alexander Calder’s crayon-colored mobiles hanging in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC:

and (right) WBryson16 on Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Then watch the sophisticated engineering in the movements of George Rickey’s stainless steel sculptures in these two short videos:

You can see four of Rickey’s outdoor sculptures (left-to-right) in Indiana, New York, California, and Germany, including a painted one (photos by Wikimedia Commons user IH Havens [CC BY-SA 4.0], Flick user Sébastien Barré [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0], Flickr user rocor [CC BY-NC 2.0], Wikimedia Commons user Rufus46 [CC BY-SA 3.0]):

George Rickey: A Life in Balance is the first biography of his fascinating creations and life, from his early childhood to the end at ninety-five. What stands out above all is how he used his technical, mechanical know-how, great intellect and knowledge, and a slew of personal connections to keep pushing himself to new frontiers, becoming a prolific moving sculpture artist (3,000 pieces). To understand his groundings and influences, Belinda Rathbone offers a take-a-village perspective.

This is not Rathbone’s only biography of an artist, nor the first time she’s been the first to write one about an artist: on the Depression-era photographer in Walker Evans. She’s also the author of another biography about her father (when he was the head of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts) and the controversy surrounding a famous painting: The Boston Raphael: A Mysterious Painting, an Embattled Museum in an Era of Change, & A Daughter’s Search for the Truth.

On first impression, the art historian’s newest biography is handsome: dust jacket, page design with a ball hanging down to organize its thirty-five chapters, and nearly thirty illustrations in black-and-white and color. Along with its captivating literary and accessible scholarly prose, it’s the right impression as everything about this book is high quality.

Which explains why a blog that has never reviewed a biography wanted to share this book with you. If you’re of a mindset (like I typically am) that biographies are dry (whereas memoirs aren’t), you’ll be captivated by Rathbone’s exceptional prose and impeccable research. It was on display in her memoir The Guynd: Love & Other Repairs in Rural Scotland (see https://enchantedprose.com/the-guynd-love-other-repairs-in-rural-scotland), the impetus for appreciating the author and ignoring the genre, knowing it would read like historical art fiction and memoir. It’s even better, providing insight into how a great artist became a real one.

Starting with Rickey’s childhood, when he lived in Indiana until he was five. His family (the only boy among five sisters) moved to Glasgow, Scotland so his MIT engineer father could manage the huge Singer Sewing Machine Factory in Clydebank nearby, not like the smaller plant he oversaw in South Bend. Before they left, Rickey spent time with his grandfather, a clockmaker, a formative experience that gave him an “appreciation for mechanical structures and the intricate handwork” and the concept of a pendulum, which played out years later in the precision and intricacy of his moving sculptures. Rickey gained a different kind of appreciation for how things work and the skills needed when he observed the making of the world’s most popular sewing machine. Sent to boarding schools as a teenager, first in Scotland where he met his life-long mentor, George Lyward, who inspired him to do the same when he returned to the Midwest and taught history and studio art at colleges. Lyward understood that Rickey was no longer as passionate about math and science as history; he transferred to one of Oxford’s colleges (Balliol built in the 1200s), where as luck would have it he stumbled on the Ruskin School for Drawing. John Ruskin, 19th century British writer/painter/more, is just one of the names cited in this book dense with so many who in some way influenced George Rickey.

By Tony Hisgett from Birmingham, UK [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Special people and fortunate events in Rickey’s life by eighteen show a pattern that continued for much of his life, opening a door that led to another, another and another, until he became the one sought after by museums and art galleries in the US and Europe. Eventually, he reached the point that he had to hire assistants or he couldn’t possibly keep up, despite his boundless energy, work ethic, and desire for simplicity. The studio where most of this happened started out as a barn on acreage in East Chatham, New York, with a dilapidated countryside farmhouse he bought with his first wife, Susan. As the money came in, the house and studio were renovated repeatedly to make room for his expanding collection; when still there wasn’t enough space he acquired other properties. His second wife, Edie, managed them. More about her below.

So many people, known and unknown to us, made a difference in Rickey’s artistic and personal life. Amazingly so. A legendary name, Andrew Carnegie, gave him his real start as the recipient of the first Carnegie grant for an artist-in-residence program at colleges, pioneering this type of grant and program. Initially, Rickey taught history and art, then combined the two teaching art history. As jobs, responsibilities, and his reputation grew, he’s seen hopping around the country taking on bigger and more challenging positions. Then in the late 1920s he spent time in Paris, that famous era of the Lost Generation. Those years and later when he lived in New York City with Susan, he felt freer to experiment with abstract art. After the Depression, he pushed himself more and never stopped. His is a stunning story of an artist constantly moving and changing in sync with historical times when art was changing too. It wasn’t until after the Vietnam War and dream-destroying political assassinations that he turns to Europe, especially in West Berlin and Rotterdam, becoming hugely popular internationally in the 1970s.

As a story of two marriages, his life becomes more relatable and not all highs. Mild-mannered and steady, Rickey’s unstable wife Susan became an obstacle to his work and peace of mind, but it wasn’t easy to divorce her. His second marriage to Edie, much younger and taller, represented decades of highs until alcoholism took its toll. For much of the book though she’s his “flamboyant,” “theatrical” opposite partner devoted to promoting his work and managing it like a “boardroom” meeting, she the Chairman. As a father, he comes across as not having enough quality time with his two sons, Philip and Stuart. Yet his influence on them is seen by their both becoming artists and Philip heading up the Foundation that carries on his father’s legacy.

The Edie years when she was at the center of Rickey’s art make this both an engrossing story of a great artist and a “couple’s life in art.”

Lorraine