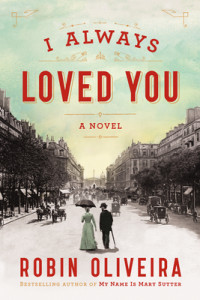

Love and Impressionism: Picturing the forty-year relationship between Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas (Paris, 1877 to 1927): Is it any wonder that Robin Oliveira has achieved her lofty goal in I Always Loved You of creating an historical novel with a “soul”? Guided by research that sounds as passionate as her artist characters – she’s read 70 – 80 books, traveled 20,000 miles, offers 40 links on her website to artworks cited in her novel – she delves into and shapes the tumultuous, complex relationship between one of the most influential artists of Impressionism – Edgar Degas – and the American woman who exhibited “more pictures in Paris than any other” – Mary Cassatt – and asks if it was Love?

Love and Impressionism: Picturing the forty-year relationship between Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas (Paris, 1877 to 1927): Is it any wonder that Robin Oliveira has achieved her lofty goal in I Always Loved You of creating an historical novel with a “soul”? Guided by research that sounds as passionate as her artist characters – she’s read 70 – 80 books, traveled 20,000 miles, offers 40 links on her website to artworks cited in her novel – she delves into and shapes the tumultuous, complex relationship between one of the most influential artists of Impressionism – Edgar Degas – and the American woman who exhibited “more pictures in Paris than any other” – Mary Cassatt – and asks if it was Love?

In imagining a conflicted, emotional story of two great artists who shared a deep, enduring admiration for each other’s artistry and devotion to their art, Oliveira sets out to answer the question, “Was there room for love in two lives already consumed by passion?” She was inspired by the knowledge that Cassatt, at the end of her life and upon Degas’ death, burned a lifetime of their letters. In re-creating them, the author offers up glimpses, as Degas revealed his affections to Mary in his private communications but was bewildering and unknowable in public.

Digging deeper, the author examines “what is love,” “what is happiness?” in many dimensions, staying close to history. In so doing, she gives us a veritable “Who’s Who” of an amazing circle of artists, many friends with each other, sometimes entangled relatives, an Impressionism 101 cast of characters that also includes forerunners to Impressionism – Realism – and those who soon followed – the Post-Impressionists – and others who affected the impressionists such as art critics, writers, and art dealers. The list of famous and not-so-familiar names is long. That the author has executed all of this in such a tightly woven novel (343 pages) is quite impressive.

What this means for the reader is that I Always Loved You is packed with little details that if you turn the pages too quickly you are likely to miss. So take your time reading this novel, it begs us to linger, maybe even take some notes as I did, because there’s so much art and cultural history behind the telling of Cassatt’s and Degas’ story, organized in appropriately short chapters because they are dense with tidbits of information.

The heart of the novel takes place from 1874 to 1886. The Belle Époque was a golden, peaceful time in France’s history (post-Prussian War/pre-World War I), when the modern city of Paris was designed and born. It seems no other city could possibly be more in love with art, or be more enchanting and beguiling. Enter the Impressionists: a “new school of painting” whose appreciation took many years, after being mocked by the classical painters, rejected by the Paris Salon – the premier art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, where academic techniques reigned supreme, intimacy shunned. The impressionists, on the other hand, rejected their conservatism, favoring brilliant colors in gorgeous natural and artificial light that exposed the most intimate of moments in everyday Parisian life. “Paint what you see,” “paint what you love,” Degas mentors Cassatt, his enduring legacy of love to her.

For although this novel is peopled with the likes of the Manet brothers (handsome, bon vivant Édouard and goodly Eugène) and Eugène’s wife, impressionist painter Berthe Morisot (a lifelong love for the brother, the brother for her, and struggling with painting after motherhood); Monet, Cézanne, and Renoir (“traitors” for exhibiting at the Salon); Camille Pissarro and Gustave Caillebotte (gentlemanly, “beloved”); Félix and Marie Bracquemond; Zacharie Astruc; Émile Zola; Paul Gauguin; Henri Somme and so many others (Sisley, Durand, Daudet, Ingres, Lebourg, Delacroix, Raffaëlli, Tourney, Zandomeneghi), they are still the background framing a stirring picture of Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas, who sought each other out in this teeming milieu because they admired each other’s work so much.

When Mary first arrives in Paris from Pennsylvania, she obsesses and struggles with her art; no matter how disciplined and hard-working, she doubts she’ll ever achieve excellence over technique. It’s Degas who encourages her to experiment with color and light. She is in awe of how Degas can keep his “brush stroke so light yet communicate so much.” Once he awakens in her a new way of seeing and creating, she feels she “cannot live without him.” Their relationship is up and down, over so many years. Both never marry. Was theirs a romantic love, or were they emotionally bound to a deep respect and love for each other’s art?

Besides focusing on the complexities of the multi-faceted theme of Love, the plight of these struggling Parisian artists, many living in poverty, others struck down by serious illnesses, is another big theme. Degas remains the purist to his passions, antagonizing, alienating, scorning any artist he believes has sold his soul to make a living, which includes exhibiting at the esteemed Salon. So, he, for example, feels Renoir will “prettify anyone for enough coin.” Renoir, in turn, is critical of Degas’ sculptural, radical masterpiece, Little Dancer. Degas is so obsessed with perfectionism that after a year of working side-by-side with Cassatt to produce an avant-garde journal of sketches and prose that involves painstaking work on an Italian printing press backs out at the very last minute, without even telling Mary, who gave up a year of painting for the project and Degas. She is, of course, infuriated, one of many times Degas has been dismissive, uncommunicative, unreliable. What she doesn’t know is how alike they really are. Degas recognizes they are kindred souls: he too fears his work is not good enough and, despite what Mary thinks, it does not come effortlessly.

Key characters suffer from chronic, debilitating illnesses, which given the century are poorly understood and badly treated. Some accept their situation with incredible grace: Lydia, Mary’s older, loving sister, often sat for Mary, never married either; and Abigail (May) Alcott Nieriker (yes! Louisa’s sister) who seemed to have everything Mary did not (acceptance at the Salon, a happy marriage), whose life seemed so easy until a terrible childbirth. Two illnesses are particularly cruel: Degas’ progressively degenerating eyesight which he kept hidden except from Mary – an artist who loves light but is going blind; and Édouard Manet’s decline from “Napoleon fever” (syphilis) caused by his illicit dalliances, embarrassing and painful for a man who loved life and people.

Knowing how vital Parisian light was to the impressionists, the author’s prose is wonderfully sprinkled with numerous references to light: “Paris is shining” in its “footlights” and “gaslamps,” falling light, half-light, dawnlight, candlelight, soft light, grey light, afternoon light, “light of southern France,” “washed darkness.” For Mary, “color and light are all she has in the world by way of her tools.” The same evocative prose holds true for the author’s depiction of this Parisian era – Victorian and Old French – words such as cheval glass, décolletage, fiacre, abattoir, abonnés, vitrine.

Mary’s awfully protective father, Robert, wants to know what it “means to be an artist in Paris?” Thanks to a gifted writer (and researcher), we have a much better answer to his question than when we started.

Happy Reading in the New Year! Lorraine