Timeless lessons on love and life learned in a timeless city (Oxford, England, present-day): A big shout out to My Oxford Year. It’s everything you want in feel-good, romantic fiction. I’m shouting having just given up on a stretch of dark, rambling novels, cheerful this one shines bright and crisp.

Timeless lessons on love and life learned in a timeless city (Oxford, England, present-day): A big shout out to My Oxford Year. It’s everything you want in feel-good, romantic fiction. I’m shouting having just given up on a stretch of dark, rambling novels, cheerful this one shines bright and crisp.

Due in part to an uplifting premise: idealistic, brainy, red-headed Julia Roberts-like, twenty-five-year-old “Ella from Ohio” seizes her “Once-in-a-Lifetime Experience” to study at Oxford (Victorian literature; Victorian poetry introduces each chapter) on a Rhodes scholarship, vowing a year of “pushing boundaries, and exploring new things.” Largely, though, because Julia Whalen knows her way around words.

While this is Whalen’s debut as a novelist, she’s no stranger to words. A screenwriter asked to rewrite the words for the screenplay Oxford by Allison Burnett, which inspired this novel, she’s also been tuned to expressing words as an actress and as a narrator of a bestselling list of audiobooks like Kristan Hannah’s newest The Great Alone and Gone Girls. Now it’s her turn to craft “words that hold clues.”

Ella Durran, despite all her best laid game plans, has fallen for a man with a secret: strikingly handsome Jamie Davenport known for breaking hearts. They meet under the worst circumstances, swiftly set up in a series of cinematic scenes. No surprise that a movie is in the works.

Ella arrives in Oxford disoriented and exhausted. On her way to a fish and chip restaurant, she’s nearly run over by Jamie driving a snazzy, Aston-Martin silver convertible with a blond passenger. Soon there’s an incident in said restaurant that causes a commotion when Jamie accidentally crashes into Ella whose carrying her meal with a sampler of messy sauces, resulting in Ella barking “you posh prat.” Next we find Ella seated in her first class stunned that Jamie’s filling in for the legendary English literature professor she’d hung her dreams on.

You’ll laugh and smile page after page at Ella and Jamie’s cut-to-the chase, witty, teasing repartee, full of sexual innuendo. Their off-to-a-terrible-start relationship contrasts with an eccentric trio of lovable friends she instantly hits it off with: Charlie, her dormmate at Magdalen College, one of Oxford’s thirty-eight architectural marvels, with a flair for the overly dramatic and a passion for literature that matches hers; classmate Maggie with pink hair; and their mutual friend Tom, an ex “linguistics, philology, and phonetics” Oxonian Maggie has a crush on but he’s so absent-minded she can’t even get to first base. These fun “Three Musketeers” are with Ella from beginning to end, teaching her the cultural ropes, watching her back.

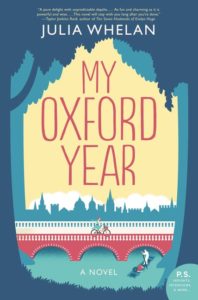

We get to know this wacky cast of characters through sharp, erudite, comical dialogue that also conveys interesting tidbits about Oxford’s history, historic sites and hangouts. The novel’s cover is a charming rendition of its famed Bridge of Sighs and Thames River rowing tradition. Later, Jamie’s upper crust parents enter the picture, adding more colorful characters and the aristocratic side.

Oxford Bridge of Sighs

By Brian Jeffery Beggerly [CC BY 2.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

The author labels My Oxford Year a “romantic dramedy.” A term that nicely sums up it feels more lighthearted than it actually is. Ella’s no shrinking violet and her friends are amusingly over-the-top. yet when she discovers Jamie’s secret your heartstrings will be tugged until you find yourself crying. All in all, you’ll come away joyful for an irresistible read lovingly depicting the City of Dreaming Spires. Ella, who narrates, sees Oxford as a “novel come to life.” Similarly, the novelist evokes Oxford as “history with a pulse.”

Oxford

By SirMetal [Public domain]

from Wikimedia Commons

The novel opens just as she approaches the British customs official. Not the ideal time to receive a call from the newly departed White House chief of staff offering her a plume Washington job as education consultant for another rising star, a junior senator and widowed mother of three running for President. A quick thinker in spite of her jet-lagged condition, she finagles a deal to consult from Oxford for the year, which, of course, means romantic entanglements are seriously compromised and she’s on call 24/7. She juggles and manages that intrusive feat like a pro.

Not the case with Jamie who poses an existential threat to her “Oxford destiny” perhaps predictably, but you’ll relish the seduction so who cares. When Jamie gazes at her with his soulful blue eyes, she’s like “a boat caught in a current.” Beyond the physical seduction, she comes to understand how much deeper he is than that. If she wasn’t so rocked and stewed about his taking over the class of her professorial heroine, she might have gleaned Jamie’s poetic qualities simply by the nature of his poetry assignment. Jamie is all about feelings:

“To truly experience a poem, he mutters almost to himself, you need to feel it. A poem is alive, it has a voice. It is a person. Who are they? Why are they?”

Jamie’s lessons are about love and life and how far you’re willing to go for what really matters, if you can even figure out that profound question, dig really deep, and then come to grips with and act on that truth. “If you don’t open yourself up,” Jamie says, “how can you be surprised by life? And if you’re not surprised, what’s the bloody point?” Jamie’s definition of pushing those boundaries wasn’t quite what Ella had in mind.

Whalen describes Jamie’s mesmerizing eyes in a writing style that beautifully shows rather than tells. They are, Ella realizes:

“the color of this swimming hole I used to spend summers at as a kid, at the end of a trail, at the base of a waterfall. The color was so magical I was convinced if I could hold my breath long enough, swim deep enough, pump my legs hard enough, I’d discover the bottom wasn’t a bottom at all, but a portal to another world.”

So too can be said about My Oxford Year. Magical, it takes us to another world. To an ancient city that “belongs to everyone.” Delivering a universal message that speaks truth to us all.

Lorraine