“Stage-struck”: From poverty to Broadway (Bronx/Brooklyn, NY, 1914 to 1930): Beautifully written storytelling that stayed on the bestseller list over forty weeks when first published in 1959 – a book with devotees in and out of the theatrical world – is too good for Enchanted Prose to pass up because it’s not fiction. Deeply felt books like this one seem to take on a life of their own, much like Moss Hart said a play has “its own peculiar and separate life.” And like playwriting, blogging does not come with absolute rules. For as much as Moss Hart’s can’t-put-it-down storytelling memoir, Act One, renders a detailed, behind-the-scenes account of a famous playwright’s “lifelong intoxication with the theatre” (he wrote The Man Who Came to Dinner, You Can’t Take it with You, A Star is Born; he directed My Fair Lady, Camelot), it also offers what enchanted fiction ought to do: stir the heart and take us inside the human condition. For those who don’t read enough memoirs, Moss Hart’s elegant prose might change that. Yes, it’s that good.

“Stage-struck”: From poverty to Broadway (Bronx/Brooklyn, NY, 1914 to 1930): Beautifully written storytelling that stayed on the bestseller list over forty weeks when first published in 1959 – a book with devotees in and out of the theatrical world – is too good for Enchanted Prose to pass up because it’s not fiction. Deeply felt books like this one seem to take on a life of their own, much like Moss Hart said a play has “its own peculiar and separate life.” And like playwriting, blogging does not come with absolute rules. For as much as Moss Hart’s can’t-put-it-down storytelling memoir, Act One, renders a detailed, behind-the-scenes account of a famous playwright’s “lifelong intoxication with the theatre” (he wrote The Man Who Came to Dinner, You Can’t Take it with You, A Star is Born; he directed My Fair Lady, Camelot), it also offers what enchanted fiction ought to do: stir the heart and take us inside the human condition. For those who don’t read enough memoirs, Moss Hart’s elegant prose might change that. Yes, it’s that good.

This new edition (Act One has never gone out of print) coincides with the Lincoln Center’s production currently playing in New York City. Dedicated to Hart’s wife of 15 years, actress/TV personality, Kitty Carlisle, it’s been updated with a moving forward by their son, Christopher Hart, a director/producer.

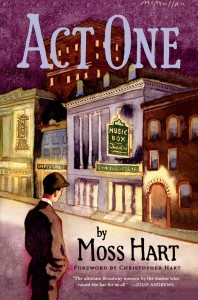

Act One is as physically alluring – oversized and the cover golden — as the drama it portrays. It is not the whole of Moss Hart’s life, which is why the aptly titled “Act One.” (Dazzler: The Life and Times of Moss Hart by Steven Bach, 2007, presents Act Two, which includes Hart’s battle with manic depression. Sadly, there is no Act Three, Hart dying early at 57 from a heart attack.) Not that Act One, Hart’s coming-of-age story spanning ages 10 to 26, is entirely a happy journey either, but it’s full of triumphs you’ll want to cheer.

Poverty is the backdrop, overshadowing everything. It “dulled and demeaned each day.” Poverty Hart characterized as “thievery,” robbing the vitality out of his unemployed Jewish father (a cigar maker from England) and his also jobless brother. Hart makes the uncommon point that it’s not just the lack of money that degrades and wears down the soul:

“It is hard to describe or to explain the overwhelming and suffocating boredom that is the essence of being poor …. Boredom is the keynote of poverty – of all its dignities, it is perhaps the hardest of all to live with – for where there is no money there is no change of any kind, not of scene or of routine.”

Poverty intensified Hart’s passion for Broadway at a time when it flourished in the 1920s, with some 70 theatres. (His attachment to his eccentric, theatre-loving Aunt Kate, who once lived with his family, another influence.) His addiction for this “devilish profession,” which he claimed is “the most difficult of literary forms to master,” is all-encompassing. Act One, then, is about sometimes “wanting so much it can suspend judgment, intelligence, or plain common sense.” It is always about what it takes to lift oneself out of an unrelenting human condition: the “boldness to dream,” courage, endurance, discipline, talent, “sense of timing,” and good old-fashioned luck.

One explanation Hart suggests for the magnetic appeal of the theatre is that it serves as a “refuge of the unhappy child.” Indeed he is a lonely one, out of sync with most of his family and schoolmates. So we almost expect he’ll drop out of school at a tender age, which he does. And then we root for his burning wish to get his foot in the door of Broadway, which he does. The prose draws us in, so we can picture ourselves seated beside him and his Aunt in the theatre nightly, his theatrical office job coming with the fantastic perk of free tickets. Of course, Hart also desperately needs money. When he finally earns some, slowly and painfully – out-of-town flops, social directing during an interesting era in American culture when “adult summer camps” proliferated – with his first Broadway hit, Once in a Lifetime, he consciously sets himself on a path of a lifetime of indulgences. He makes no apologies for “excess;” he touts it as the purpose of money. While most of his “shopping sprees” go beyond the scope of this first act, we don’t fault him when he gets “clothes drunk.” No, we completely understand.

Much of Act One is a story of mentors and collaborators, the most important being the legendary, Pulitzer-Prize winning playwright, George S. Kaufman. The writing is so well-expressed we can see both men madly pouring over scene fixes for Once in a Lifetime at Kaufman’s brownstone on the Upper East Side. Kaufman is a rather eccentric fellow – rituals of hand-washing, barely ever eating versus Hart’s voracious appetite, proud baker of wicked sugary fudge so the two can stay awake through regular all-nighters. Kaufman’s “surgical” pencil looms very large here.

Considered one of or perhaps “the best book ever written about the American theatre,” Hart makes sure we understand it is like no other. As far as he is concerned, there’s no “other profession as dazzling, as deeply satisfying as the theatre.” For Hart, the “four most dramatic words in the English language [are]: Act One – Scene One,” and the “jolliest sounds in the world” are the “buzz of anticipation of a fashionable audience.” Although he recognizes there are other careers more “noble,” none are as “sweet.” While we might not agree, you’ve got to admire the zealous devotion and fellowship. Hart, though, admits the theatre takes a “tremendous toll” … on “nerves, in strain, in stamina – that it takes as much as it gives.”

Unquestionably, Act One delivers insightful and delightful commentary on playwriting and the “mystique” of the theatre:

“Never again a sound of trumpets like the sound of a New York opening-night audience giving a play its unreserved approval … no audience as keen, as alive, as exciting and as overwhelmingly satisfactory as a first-night audience taking a play at its heart.”

For playwrights and anyone wishing to be part of this artistic world, Act One is a gift of an insider’s observations on a range of theatrical topics – the importance of understanding the anatomy of a play; what makes great actors; sizing up pleased/displeased audiences; cultivating an “esprit de corps;” the promise of auditions and the disappointment of dress rehearsals.

While Hart’s commentary is laden with worries – by nature he’s a “chronic worrier” – let’s put aside these concerns for the moment. Instead, let’s jump for joy when the acclaimed Kaufman magnanimously tells the opening-night audience that the success of Once in a Lifetime is “80%” Hart’s. They have dissected and re-written Hart’s play so many, many times it’s heartbreaking and heartwarming. For you cannot help but be inspired that they don’t just give up. (Kaufman at one point did, leaving it to Hart to find their way back.)

When at long last the collaborators land their Broadway hit, Hart tells us “there is no smile as bright as the box-office man the morning after a hit.” I’d venture to guess that if you were standing in front of that box-office window you’d be smiling brightly too.

Applause! Applause! Lorraine