Romantic folk-telling – A folk hero couple in Brazil’s outback (Northeast Brazil, 1922 -1938): If Victoria Shorr hadn’t lived in Brazil for ten years, I doubt she’d have written, or we’d be treated to, this unusual historical novel about nomadic banditry “full of beauty and danger,” at a time and place completely unfamiliar to most of us.

Romantic folk-telling – A folk hero couple in Brazil’s outback (Northeast Brazil, 1922 -1938): If Victoria Shorr hadn’t lived in Brazil for ten years, I doubt she’d have written, or we’d be treated to, this unusual historical novel about nomadic banditry “full of beauty and danger,” at a time and place completely unfamiliar to most of us.

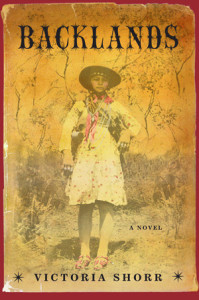

In fluid, mystical storytelling, Backlands lets us imagine what it might have been like for two legendary Brazilian outlaws – Lampião and Maria Bonita – to have roamed a remote, desert-like landscape “cut loose, as if by magic, from the worries of the rest of the world.” The surprise is how much we have in common with the humanity of the couple’s motives and passions – powerful themes of justice, fairness, freedom, happiness.

As much as Shorr’s debut novel is about two hero bandits whose hearts were stirred by music and dancing, it’s also about a sweeping terrain called the Sertão, where they hid out “under the stars” for so many years. The reader, too, is swept along by a landscape that makes you feel:

“overcome by the beauty, the light, coming across the vastness, a color of light you’ve never quite seen before … an endless stretch of wilderness, ‘caatinga’ they call it, dotted with thornbrush and all kinds of cactus, though it isn’t quite a desert. There are trees, thick, beautiful trees, well-shaped and spaced, as if planted in an English park. ‘A vast garden with no owner,’ the great Euclides called it a hundred years ago, and it’s still true. You listen, and hear nothing, and then goat bells in the distance.”

The gentle prose isn’t meant to fit the decades of violence that spread throughout an area the size of Texas in the 1920s and 30s, by a gang of bandits led for fourteen years by Virgulino Ferreira da Silva, known as Lampião, before joined for another eight years by his “Beautiful Maria.” Instead, it evokes their hearts, in soft, melodious prose that could easily be read aloud, like legends passed down through the ages orally.

Because the outlaws, like their culture, were deeply religious, spiritual, superstitious – praying to saints to protect them, bring rains on their parched goat farms, keep them alive – there’s an otherworldly aura to the novel. Even its copper-sepia cover is dreamlike.

The Sertão, “bigger than Brazil,” is backcountry so removed from the rest of Brazil, “almost another country,” I’d guess most Brazilian’s haven’t even ventured there. But legends live on.

Still, if asked to name outlaws who’ve lived on in folklore, films, and books, Bonnie and Clyde, Jesse James, Billy the Kid, Pancho Villa would come to mind. Surely not Lampião and Maria Bonita, unless you studied or fancied folklore history. The Portuguese, who came to Brazil in the 1500s, have a word for these do-gooder outlaws: cangaço. And, there’s a journal devoted to outlaw heroes, along with a term to describe them: “social bandits.” So, this is a tale, comprised of many tales, of polite banditry (“murder and courtesy”) about a “bandit with a good heart” and the younger woman he loved.

The Sertão is a strange mix of American southwestern cowboy country, Australian outback, and something more fantastic given the waters of the Rio Sao Francisco that slice through it and the “very exotic bush with a beautiful shape and large base called an ‘Umbo” tree that can thrive without the water, their fruit and shade could save you in the desert.”

On its lands live the rich and the powerful, but mostly the poor, the very poor, the powerless. The rich were corrupt politicians and wealthy landowners, especially those who lived on the coast. The poor were those who managed “day by day,” simple lives raising goats, some cattle, and in the best of times, some cotton. They were also the ones whose boundaries were trampled on, possessions stolen, and killed when the droughts and famine came, plentiful in this area near the equator.

Lampião

via Wikimedia Commons

That’s what happened to Lampião’s family, including the murder of his father. He’d been a “law-abiding cowboy” who tried to avenge and honor his family’s injustice in court. But when he failed, he chose to go outside the law, to vindicate all his people, stealing from the rich to help the poor. Regardless of who chased and betrayed him – police, soldiers, mercenaries – he always outsmarted them. Twenty years without getting caught is a long time. (There’s “no such thing as old age for bandits.”) Except during the month of July, when Lampião believed his fate would be sealed. The reader senses the fatalism. Knows what matters is the romanticism of the journey we’re on.

The historical backdrop is a 200-year history leading up to the time when a new President, Getúlio Vargas, came to power in 1930. He sought to centralize and improve his country, which meant ridding those who terrorized it. Not easy when the “King of the Bandits” was venerated as a “thunder god” – untouchable, beloved, protected by the people.

Lampião and Maria both had charisma and style. Lampião was the bravest one, a natural leader, expertly skilled with an exceptional tracking eye (he’d lost one, injured by cactus) for the land he loved:

“Loved the very distances, the great broad vistas with nothing to break them, loved the fact that it couldn’t be tamed, couldn’t be trusted, and loved even what it took from them to survive.”

Moving back and forth in time within chapters, the novel is told in stories: of halcyon days and of the bandits’ escapes from the law, militias, anyone seeking glory to capture the “most wanted man in Brazil.”

Maria Bonita

via Wikimedia Commons

Escape was also Maria’s reason for becoming a bandit. She escaped an arranged, loveless marriage at age 16 (how else could a poor family care for 11 children?) to an old shoemaker, six lonely, miserable years until the day she heard Lampião singing. She instantly knew he was her destiny, despite the risks. He famously sang about teaching love (in exchange for lacemaking, which the women did.) When they danced together, “she felt she was dancing for her mother, too, and her grandmother, her aunts and cousins, especially the ones who died young. Died of old age at thirty – the poor.”

All the characters are based on real historical ones, such as members of Lampião’s gang, like his brothers, Levino and Ezequiel, and, of course, his enemies. One was a lieutenant on the Piranhas (one of the region’s seven states) police force named Bezerra. The author has structured her novel to give voice to these two perspectives: a voice that speaks for the bandits governed by loyalty and love for their leader, a code of rules, and a “never-ending fear” of being caught. Often that voice is Maria’s. The other voice speaks for the police, forever trying to catch the outlaws. Nicely sprinkled throughout are newspaper accounts of so many who “seemed to have fallen in love with Lampião.” Why not? When he was happy, “it was like a warm soft blanket over them all.”

Lampião was “so interwoven with the fabric of life in the Sertão that to destroy him you’d have to destroy that fabric.” Which brings us back to where we began: An unusual novel about unusual banditry, fighting for a way of life totally unfamiliar to us. And gone. Until now.

Lorraine