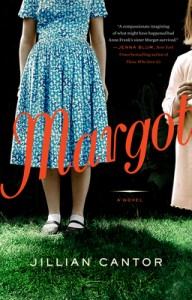

CREATING A NEW LIFE – Margot Frank died 1945, Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp/Margie Franklin re-born 1959, City of Brotherly Love: Goosebumps! That’s how stirred I felt when I reached page 322, the ending of this superb, haunting novel. Narrated in a voice haunted by her past, it is written by an author herself “haunted” by the story of two sisters who perished during the Holocaust, Anne and Margot Frank. Anne we famously know because of her found diary; Margot we barely know although she too wrote a diary, inexplicably lost. “In creating Margie/Margot,” Cantor (explaining in an elaborative “Author’s Note,” the best I’ve encountered) “wanted to give back what was stolen from her [Margot], even if only in a fictional world.” Cantor has certainly done that, memorably.

CREATING A NEW LIFE – Margot Frank died 1945, Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp/Margie Franklin re-born 1959, City of Brotherly Love: Goosebumps! That’s how stirred I felt when I reached page 322, the ending of this superb, haunting novel. Narrated in a voice haunted by her past, it is written by an author herself “haunted” by the story of two sisters who perished during the Holocaust, Anne and Margot Frank. Anne we famously know because of her found diary; Margot we barely know although she too wrote a diary, inexplicably lost. “In creating Margie/Margot,” Cantor (explaining in an elaborative “Author’s Note,” the best I’ve encountered) “wanted to give back what was stolen from her [Margot], even if only in a fictional world.” Cantor has certainly done that, memorably.

The power of this beautifully paced novel is not only in its heart-tugging story – that Anne Frank’s sister, Margot, somehow managed to escape the Nazis and assumes a new, non-Jewish identity as a legal secretary in Philadelphia – but in the way the prose exposes the hidden, ghost-like, terrified shell of Margie Franklin. Like Margie, it is subdued, delicate, unadorned, yet it is deeply felt. Margie/Margot’s story and the converging storylines are, of course, emotionally heavy and complicated.

Some images and phrases are repeatedly employed that help create the haunting effect. The indisputable evidence of the horrors Margot endured as a young girl: the forever-inked, tattooed identification number Margie fervently and fearfully always hides, by wearing sweaters, regardless of the sweltering heat. She is constantly wrapping herself up tightly in them whenever she’s frightened or reminded of her past, which is all the time and everywhere. To convey how all-encompassing these painful reminders are Cantor has structured her novel not in separate chapters that weave back and forth between 1940’s Margot and 1959 Margie, as you might expect, but rather paragraph by paragraph, as memories naturally flood Margie. That Cantor does this so clearly and so seamlessly is a testament to her fine writing skills.

Margie Franklin is a very lonely woman in her thirties, who feels “sometimes we breathe because we have to, not because we want to.” She does have a lively friend at work, Shelby, and loving sponsors, Ilsa and Bertram, but even they do not know who she really is so her loneliness and fears are palpable:

“You cannot imagine what it is like to hide until you’ve done it yourself … You cannot understand the fear that courses through you … The fear of discovery, it is the kind of fear that makes your heart feel always full, pounding too fast. It is the kind of fear that keeps your eyes pried wide open at night amid the dark and the snores of your parents, even if you haven’t slept in days. And, it is a fear that does not go away, even now, even fifteen years removed, in a new city, with a new name, a new religion, a thick sweater.”

Margie is obsessed with memories of Peter van Pels, who was among those hidden by Miep Gies in an Annex with the Frank family in the Netherlands in 1942, when Dutch Jews were rounded up and transported to Nazi concentration camps. Seventeen-year-old Margot and Peter made a survival pact to meet in the City of Brotherly Love, change their names (he to Pete Pels), assume non-Jewish lives, and marry. Margie’s love and search for Peter preoccupies her throughout the novel, and gets very mixed up with her growing feelings for her Jewish boss, Joshua Rosenstein.

Descriptions of eyes are also deftly repeated, presumably because eyes mirror one’s soul. Margie finds she cannot hide from a Holocaust survivor who immediately recognizes their shared, emptied look. Margie thinks about her sister’s “sunken eyes,” Peter’s “blue eyes, the color of the ocean,” but it is Joshua’s “gray-green” eyes we’re told most often about it. They evoke the softness and empathy of a man who cares about anti-Semitism, but as an American Jew cannot possibly understand what persecuted European Jews endured and lost.

Setting this novel in 1959 is brilliant. It provides the perfect backdrop for tormenting Margie/Margot, since this is when the movie, The Diary of Anne Frank, is playing at theatres everywhere, endlessly. Margie’s circle may be small but it seems everyone in her world has seen it, talks about it, thinks they know the true story. But this is only a glamorized Hollywood version of the truth, and maybe not even that.

The ’50s was also a time when anti-Semitic acts were committed in Philadelphia. These provide another torturous storyline: Joshua wants to litigate a class action suit against a wealthy businessman engaging in anti-Semitic business practices towards his Jewish factory workers, and asks Margie to help. This ignites profound internal emotions, including the fact that she must do this secretively – more hiding – because Joshua’s father, Ezra, a partner in the law firm is adamantly opposed to the idea. He “seems to think greatness and money are the same thing, but you know what I think greatness is?” Joshua asks and then answers: “Finding something that terrifies you and then doing it anyway.”

Lately, there have been a number of popular novels fictionalizing the lives of historic people. Some delineate fiction from truth; others leave you wondering. Cantor goes to great lengths to separate fact from invention, another feature of this stunning novel readers should greatly appreciate.

Please share your thoughts about this book, Lorraine