A Twenty-Year Obsession: An artist and his muse (London, present; Paris, twenty years earlier): Every day for 15 years, American artist Andrew Wyeth secretly sketched and painted 240 representations of one woman, Helga Testorf. A stash that took the art world by storm when the “Helga Pictures” were fully revealed in 1986 to his wife and business partner, Betsy, who then sold them at Wyeth’s request for millions and a year later exhibited around the country. Created at a neighbor’s farmhouse, it’s amazing even Betsy was kept in the dark about their existence. Far more incredulous is that one model inspired and sustained one artist for so many days, hours, and years. In 2009 after Wyeth’s death, Betsy bequeathed his studio to the Brandywine Conservancy and Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, PA, where visitors can tour and immerse themselves in Wyeth’s bucolic world, which my husband and I recently did.

A Twenty-Year Obsession: An artist and his muse (London, present; Paris, twenty years earlier): Every day for 15 years, American artist Andrew Wyeth secretly sketched and painted 240 representations of one woman, Helga Testorf. A stash that took the art world by storm when the “Helga Pictures” were fully revealed in 1986 to his wife and business partner, Betsy, who then sold them at Wyeth’s request for millions and a year later exhibited around the country. Created at a neighbor’s farmhouse, it’s amazing even Betsy was kept in the dark about their existence. Far more incredulous is that one model inspired and sustained one artist for so many days, hours, and years. In 2009 after Wyeth’s death, Betsy bequeathed his studio to the Brandywine Conservancy and Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, PA, where visitors can tour and immerse themselves in Wyeth’s bucolic world, which my husband and I recently did.

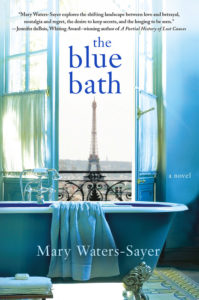

I’ve been thinking about Wyeth/Helga’s extraordinary artistic collaboration for this post: how it compares and contrasts to the fictional artist’s two decades-long obsession with his muse, rhythmically imagined in The Blue Bath, Mary Waters-Sayer’s hypnotic debut. The artist, Daniel Blake, is British. Like Wyeth, he’s secretive; we, and more importantly, the model who was his lover, knew nothing of his past. She’s Kat Lind, an American expat living in London, as the author did for twelve years.

In 1987, the Helga I saw at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC was pensive and detached, with radiant reddish-brown braids. Kat reminds me of Helga. She feels like an onlooker, and has red hair. So I thought Wyeth/Helga might be the inspiration for the novel.

Not so, says the author in an email anticipating its release, in which she discusses her inspiration. She “couldn’t shake” a portrait she noticed in the window of a London art gallery. She wondered:

“What it must feel like to be the subject of a portrait, to be examined so closely. And then I started to think about the artist and about the act of looking at someone that deliberately. It seemed so intimate.”

In Helga’s case, obviously, she was keenly aware she was the subject of prolonged study. And, since some paintings are nudes, speculation about how intimate artist and model were lingers. As for Kat: Imagine the shock of attending an exhibition at a chic Mayfair gallery twenty years after you broke off your affair with a struggling artist you met in Paris at nineteen (while studying French literature at the Sorbonne), only to discover he had not stopped painting and imagining you all these years? And, as the gloriously blue lit Parisian bathtub of the novel’s title suggests, Kat and Daniel were quite intimate. (“How rare that intimacy,” Kat reflects.) “Not since Titian has there been an artist more enamored with a redhead.” The point is dark redheaded Kat stands out. Nearing forty, will anyone recognize her?

Why this matters – the premise of the novel – is Kat never told her husband Jonathan about Daniel, wanting him to be “hers alone. Sacred and apart.” Jonathan is a made-it-big darling of the British business world, sought after by paparazzi, voracious for news about a celebrity who single-handedly “rekindled the Internet economy in Britain.” Jonathan disputes that attribution but there’s no disputing he’s an extremely rich and well-connected man. Those connections are to the very same rich people investing in art, who are mulling about the artist’s publicized one-woman retrospective. The wishing-for-greatness artist and his coarse business manager, Martin Whittaker, have kept the model’s identity secret, fueling the mystique and the valuation of the artworks.

The reader marches to the same beat as the buzz at the gallery: “Who is she and what is she to the artist?” Your clues are found in the melancholy, lyrical, seductive prose, wonderfully matched to evoke the fragile beauty of art and Kat’s delicate, elusive character. Is this what the artist saw in Kat that captivated him so?

The wistful prose conveys Kat’s unsettled soul. Like the paintings and the artist, she’s mysterious, ephemeral, vulnerable. Keep in mind that when the novel opens she’s grieving the loss of her mother. She’s just returned to London after her death, to a new home that’s being renovated in a super-luxurious neighborhood near Holland Park. This is the kind of wealth where your neighbors drive Bentleys, where you live across the street from an embassy. “The size of the house, the financial commitment, the scope of the renovation – all of these things had led her to allow herself to believe they were putting down roots.” So the disquietude we sense in Kat is meant to sound rootless, haunting.

She feels more than sad and lonely, she feels invisible. Jonathan is constantly traveling. In fact, he doesn’t physically enter the novel until the end. We judge him via absence and phone calls. He’s in China on a pressing business deal but this is his third try at negotiating it, so how crucial was it to leave his mourning wife alone? How sensitive to let her return by herself to an unfamiliar home undergoing unnerving construction? To insist their young son, Will, stay with his grandparents to give Kat a rest? Kat, in her dazed state, has too much free time on her own.

After Will, she stopped working. After Paris, she chose a vastly different path – business school. It led to meeting Jonathan, which means Kat knows those same business associates at the galleria opening. It also means, as we slowly put two and two together, that the harsh corporate world was not the best path for someone who had an eye for gentle beauty (photography, in Paris), when her life was all about “spirit and possibility.” We’re told that after ten years of marriage, hers is “comfort and familiarity.” If there was passion, it sounds gone, or silently crying out for rekindling.

How much over those twenty years Kat has thought about those heady Paris days when she barely left Daniel’s studio we don’t know. But ever since Kat learned Daniel Blake was in London and about to have a showing of his art she’s flooded with memories, woven back and forth throughout the novel. The drifting prose, her drifting thoughts, lets us feel she’s adrift. Paris left a “hole that she could feel inside her.”

Attending the opening was a risk, a bit reckless. It seems she’s drawn there by a force outside her control. Once she sees herself spread about the gallery’s walls, realizes she’s been meticulously studied over so many years, she’s unhinged. But she also grasps she has not been invisible to Daniel. A dangerous lure for someone so naked. As Kat’s mind and heart drift back to Paris, to “nostalgia and regret for a delicate and vanished time,” the reader anticipates where her story may go. The reader is right, and the reader is wrong. As the canvas gets filled in, the ending takes you by surprise.

A portending scene of Kat visiting the prestigious architectural firm overseeing the historic renovation of her home is a metaphor, I think, for perceiving Kat. Like us, the architect senses her fragility, her uncertainty, concludes “sometimes it is that which remains unfinished that remains the most beautiful.” Preservation of the palatial home is reduced to its “essential elements.”

As the story reaches its conclusion, Kat too is stripped down to preserving her most fundamental elements. To that which is indispensable.

Lorraine

This sounds intriguing. Thank you for the review.

Hope you like it, Em!

Interestingly, today in the NY Times there’s an article about the man who stored/hid Wyeth’s paintings for those 15 years! Seems he donated the land that’s part of the Brandywine Museum:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/30/us/george-weymouth-conservationist-horse-enthusiast-and-bon-vivant-dies-at-79.html

Thanks for checking in. Lorraine

Lovely review, Lorraine. I loved your take, using Wyeth’s story to shed light on the novel. Even though the author said Wyeth wasn’t the inspiration for her novel, it still provides an interesting comparison.

I thought about the paradox between the two muses: Kat and Helga. One knew she was being studied intensely and the other was unaware. The relationship to the artist would be different. I imagine Kat’s was more natural, perhaps unselfconscious. Helga may have been more confident and self-aware.

Thank you for sharing the link to the NYT article. I’ll take a look at that now.

Interesting thought and insight, Jackie, about the differences in the two models.

The Brandywine Museum and studio tours are fascinating, if you ever get a chance to get to Chadds Ford, PA! Wyeth’s studio is now a National Historic Landmark. Thanks for writing. Lorraine