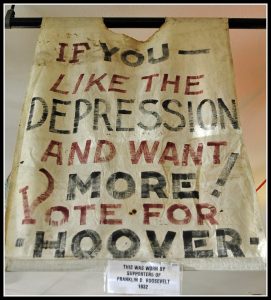

Illuminating the unsung Gilded Age legacy of socialite Alva Vanderbilt – philanthropist and activist for children’s, women’s, and civil rights (Manhattan and Newport, Rhode Island, 1874 – 1908): What Do Billionaires Owe the Rest of Us? was recently broadcast on NPR 1A, in response to the wealth tax plans proposed by some 2020 Democratic candidates. As we reflect on the extremely wealthy today, what, if anything, they owe to us, it’s worthy to look back on what the richest American families in the late 1800s – the Gilded Age era, whose name came from a Mark Twain book, did for America.

Cornelius (nicknamed The Commodore) Vanderbilt, was one of those families; he built his fortune in steamboats and railroads. Therese Anne Fowler captures the era and the family in her second novel (her debut, Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald) about another compelling woman behind the man. Except this time the woman is not known to us: Alva Vanderbilt, the wife of William Vanderbilt, one of Cornelius’ many grandchildren.

The novel is a captivating historical read. Strong-willed Alva Smith married a Vanderbilt for financial security not love. She sought to become a prominent force in the early days of establishing Manhattan’s upper-crust. An activist for children, she later became one of America’s earliest suffragettes. Today, these fights continue – for migrant children and immigrant Dreamers, voting rights, women’s, and human rights – making Alva’s story important to tell.

Interesting comparisons can be seen between Alva’s post-Civil War time period to today. Both a highly divided America: extreme poverty and the dwindling middle class versus extreme wealth; and racial, anti-immigrant, and anti-Semitic discrimination.

Newly married Alva is seen as sensitive to the plight of African American women. She fought tooth and nail her new husband’s and sister-in-law’s racial condescension towards her personal maid and confidente who was black and by her side since childhood, opposing their desire she let her go because she didn’t fit the “lady of privilege” image the family wished to project. An early example of the expectations of marrying a Vanderbilt, raising a timeless question: Is choosing wealth over principles worth it? And in Alva’s case: Can a marriage survive based on transactional benefits?

Alva acted like a well-behaved woman, but she was also fiercely independent-minded when it came to injustices – equal treatment of all children and women, including those of color. Noteworthy at “a time when many people (including those in the suffragette movement)” were not standing up for equality for all.

In the year since the novel was published, America is more polarized than ever. So now is a poignant time to read the newly released paperback edition.

There’s other reasons to sing the novel’s praises. It’s a lovely literary escape into more classical prose, manners, evoking classics like Edith Wharton’s A Custom in the Country and Henry James’ Washington Park, two of Alva’s reading choices, also set in Manhattan’s Gilded Age. Again, timely as NPR just confirmed we’re living in the second Gilded Age.

Alva’s motivation to marry a Vanderbilt at twenty-one opens the hefty novel: “Once there was a desperate young woman whose mother was dead and whose father was dying as quickly as his money was running out.” And there were four sisters who needed to be fed – Alva’s older sister, Armide, destined for spinsterhood, and two younger ones.

The Smiths weren’t always poor. Their father made his money in cotton in the Deep South until it became the “disgraced-South.” The family escaped to Paris, where they spent many lavish years before coming to New York, where they weren’t accepted into high society – the “deep-rooted Manhattanites.”

A shortage of men after the Civil War also limited the sisters’ marriage prospects. Also, Alva wasn’t a beauty to show off. What she had going for her was ancestry and cultured years in France.

By José María Mora via Wikimedia Commons

Consuelo Yznaga, Alva’s best friend, is a huge presence. A wealthy, prettier socialite whose Cuban-American father made his money in sugarcane, she fancied matchmaking, which she did for Alva with William Vanderbilt. Both women wanted the same things because “status gave a woman more control over her life.” For years, they traveled along parallel paths, Alva in Manhattan and Consuelo in England, until something terrible happened. Letters between the two over the years keep us updated. Consuelo, not so well-behaved, is flamboyantly revealing; Alva is more reserved.

Over time, we like Alva more and more, Consuelo less and less. We don’t approve of their gold-digging, but we’re sympathetic to Alva’s desperation to support her family in crisis. Alva’s strength, moral convictions, and compassion towards Consuelo’s painful behavior is admirable. Valuing friendship, another prevailing theme.

Pearls, the inviting title of the novel’s first part, focuses on Alva’s fixation on acceptance into New York’s upper class, starting with getting invited to exclusive society balls, scheming and hobnobbing with Consuelo’s help and another friend’s, Ward McCallister. A long-time friend of Alva’s family, this charming, gossipy man-about-town was close to Caroline Astor, the famous Mrs. Astor, seen holding the key to opening doors, or not. Considered queen of New York society, her Old Money world frowned on “robber barons” like The Commodore for their exploitative business practices. William seized on Alva’s attributes to help breakthrough Mrs. Astor’s disapproval of the family, so it was a marriage of convenience for both.

Alva in turn, raised to “always put sense above feeling,” that “love was a frivolous emotion,” seized on the challenge. Yet, for all the head-over-heart guidance, a sexual thread runs throughout, making Alva more relatable.

Formidable Vanderbilts posed other challenges for Alva. One,the earlier cited sister-in-law, Alice, wife of William’s brother, Corneil, who was perceived as “a shining example of all that’s right in the world.” Snobby, overbearing Alice assumed that meant her too; she aimed to be the next Vanderbilt matriarch – not Alva. Forever disparaging Alva, she gets under our nerves and Alva’s. Alva is too disciplined, wise, and ambitious to cower.

NYPL Digital Gallery via Wikimedia Commons

Less offensive and better-intended was William’s mother, related to the Roosevelts. “I don’t pretend to understand all this best society nonsense. Who’s allowed in, who’s kept out,” she says, but she certainly knows how to take charge to make that happen, “acquiring a house on Forty-Fourth Street as a wedding gift” for the newlyweds.

Of course, the house wasn’t an ordinary one. Rather, a magnificent mansion, the first of a number of their palatial properties in Manhattan and Newport, where this wealthy clan summered. Alva relished furnishing and decorating her estates.

Photo by Daderot via Wikimedia Commons

So many historical figures fill the pages, going as far back as the 1600s when New York was settled by the “best New York Dutch.” The juiciest parts of the city’s real estate development are how “family history and reputation” led to “the clear establishment of order” along the richest areas of Manhattan along Fifth and Park Avenues, setting down boundaries.

Another Gilded Age family – the Belmonts – is ever-present. The Belmont critical to Alva’s story is Oliver, one of William’s friends. Their on-and-off friendship is the real sexual tension that makes the novel hum.

Alva’s accomplishments exceeded her lofty goals, but she was lonely much of her life. Besides managing estates and entertaining to the hilt, she kept herself busy mothering three children and increasing her progressive philanthropy and activism.

Ironically, Alva learns that “existing on a joyous merry-go-round of wealth” was not enough. Finding love is what makes the world spin. Still, would she think her sacrifices were worth the greater good?

Celebrating Alva’s great deeds feels like a good way to end this year’s reviews. Wishing you peace and happiness. See you in 2020.

Lorraine