The Vagabonds – how four orphaned children survive inhumane treatment at an Indian Boarding School during the Depression: (Minnesota, 1932): “Does anyone ever get used to having their heart broken?”

That’s one of the many piercing questions gifted storyteller Odie O’Banion asks in his eighties as he looks back on four “soul-crushing” years he endured at an Indian boarding school in Lincoln, Minnesota, along with his older protective brother, Albert, and two other orphans they befriended – Mose, member of the Dakota Sioux tribal nation, and Emmy, an adorable little girl – and what happens to them afterwards in one life-changing summer in 1932. Odie’s recollections are vivid, because “everything that’s been done to us we carry forever.”

Odie’s tales are spun in gorgeous, lyrical, heart-wrenching, spiritual prose that seems destined to live on for the ages. William Kent Krueger cites as his literary inspirers great classical writers like John Steinbeck, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and Ernest Hemingway, which may partly explain why This Tender Land has “the feel of a classic” (quoted from the back cover). Odie’s storytelling brims with heart and soul.

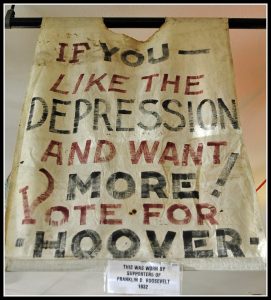

In a heartfelt letter to readers, Krueger says “in asking you to read This Tender Land, I am, in a way, offering you my heart.” He ends with “I’ve poured the best of myself into this story” – and it shows in this follow-up to his acclaimed, first stand-alone novel Ordinary Grace, also set in Minnesota, where the author lives. (Krueger is the author of a seventeen-book mystery series featuring Cork O’Connor.) His 2013 novel takes place thirty years after this tender tale set during Herbert Hoover’s Presidency, blamed for the Great Depression. In fact, the Herbert Hoover song made famous in the musical Annie, as well as the shantytown name Hooverville, appear in the novel. Emmy’s depiction is in the image of Little Orphan Annie.

To get a feel for the mood of the novel you may want to listen to Shenandoah, a melancholy folk ballad, Odie’s favorite song, he plays on his can’t-live-without harmonica, his “hobo harp.” Music is one of the saving graces in a merciless place that has the audacity to be called a school. The lyrics foretell what’s up ahead for the children:

Each of the four orphans brings a special quality to the group, which becomes the family they’ve all lost and yearn for:

Albert is deft at all things mechanical and technical, which comes in mighty handy.

Odie is the risk-taker who does things no one else would dare to do.

Mosie is the most victimized as he’s the only American Indian of the foursome, symbolizing the long and ruthless history toward the Dakota tribe in Minnesota. He arrived at the military/prison-like/forced labor camp school without a name, a family, and unable to speak. The brothers’ mother was deaf, so they knew sign language, giving Mose a way to communicate since no one at the school could talk with him. A form of isolation and trauma. As the hardest and most upbeat worker, his storyline is even more heartbreaking. “There was something poetic in his soul,” says wise and eloquent Odie. “When I played and he signed, his hands danced gracefully in the air and those unspoken words took on a delicate weight and a kind of beauty I thought no voice could have possibly given them.”

Emmy beloved by all, soothes them all.

The four form a bond early on when they worked together at an apple orchard on a farm that had fallen on tough times, indicative of the hard hit Midwestern farmers during the Depression. Still, it’s hard to imagine anyone suffering more than these four abused children, subjected to the wrath of the school’s superintendent, Mrs. Brickman. Nicknamed the Black Witch on account of her “black little heart,” she’s cruel and vengeful like a prison guard. Forever sending Odie, eight when the novel opens, for detention to a “quiet room,” a euphemism for “solitary confinement” as the terrifying cell he spent so many days alone in was a prison cell as the school was formerly a military base, Fort Sibley. A lot of history is embedded in the prose.

Good-hearts at the school were the exception. Besides the empathy these children have for each other, they had two compassionate teachers: Herman Volz, an older German immigrant, a gentle giant of a man, who taught carpentry. Like a “godfather,” his portrayal represents the large numbers of Germans who settled in Minnesota.

The other “precious gem” teacher is Mrs. Frost, who taught domestic skills to the girls. But they too were sentenced to hard labor cleaning cement, while the boys were treated like slaves by a heartless farmer, his farm on the school grounds.

If you’re unable to recall learning about the shameful history of Indian boarding schools aimed at wiping out American Indian culture, a form of genocide, that’s because it was wiped out of history books.

What happened to American Indian children nearly a century ago is not just old history, but another gut-punching point in American history that’s happening today on our southern borders, where migrant children are being held in prison-like cages.

Minnesota is located in a part of the country known as Tornado Alley. Frequent tornadoes devastate, another reminder of present-day – climate change. Combining tornadoes with tornadic, traumatizing school years, Part I is justly titled God is a Tornado.

Part II takes place four years later when Albert is sixteen, Odie twelve, Emmy six, and Mose’s age unknown but his spirit is ageless. This is when the adventure story begins. A freeing, roller-coaster time, when there’s a sense of hope mixed with hopelessness. Ever mindful of spoilers, the rest is left for the reader to discover.

Albert is an ethical young man, whereas Odie says he was not, yet he’s not afraid to rail against injustices, since “the only way to stand up against evil in this land, is to stand together.” Similarly, he says, “we are creatures of spirit . . . this spirit runs through us and can be passed to one another.” Indeed, a spiritual outlook winds through this hard-knocks novel, reinforced when a traveling band of healing evangelicals, a “revival tent show,” rekindles faith. Whether you agree with what the revivalists preached or not, they gave people that thing called Hope. Part III, then, is also spiritually titled, High Heaven.

Again no spoilers about Part IV, The Odyssey, and Part V, The Flats.

Odie is treated like “vermin,” very disturbing language that’s also timely as the President has referred to people of color and the less fortunate as “infestations.”

Odie’s stories heartily express grief, sadness, desperation, losses, but also a deep love for the grace of good, decent people and the land. Even in his elderly years, he speaks of a sycamore tree as a “thing of such beauty.”

In an Author’s Note, Krueger tells us he grew up listening to his “father’s stories about the Dust Bowl Years,” apparently the origin of wrapping his heart in the hearts of his characters, whose voices memorialize 250,000 homeless teenagers in 1932 he refers to.

The author is also after our hearts, 464 pages worth. Sixty-four chapters filled with such beautiful prose the pages fly.

Odie met another good soul who tries to comfort him saying the “heart is a rubber ball. No matter how hard it’s crushed, it bounces back.” But as Odie tells it, the heart never forgets.

Lorraine

Best book I’ve read since where the crawdads sing. I could not put it down!!! I’m not a reader but loved this book!!!

Hi Kerry,

Agree! Gulped the Crawdads down on my Kindle, so didn’t review as didn’t take notes, underline quotes that enrich reviews, but it’s gorgeously written. Krueger’s earlier novel, Ordinary Grace, which I read is sort of a companion to This Tender Land, think we’ll love. Thanks for your comments.

I enjoyed the book immensely. While I enjoyed the spiritual discussions, I felt that maybe they could have been a little less heavy handed. I was intrigued by the emphasis on behaving with love towards others theme and how that good changed others. (Most obviously Jack but also the girl’s father and the kids themselves being helped by Herman and Mrs. Foster). Also none of the reviews I’ve read talked about the title, which I thought was odd. Jack in particular talks about the “tender land” and especially in these times when climate and land use have been sacrificed it is really quite prominent theme.

Hi Kathleen,

Your comment about the title as an important theme is thought-provoking. Wish I’d reflected on the title in my review, as I often do with other books. Had I done so, I would have likely said that I thought William Kent Krueger, through his narrator and in his letter to readers, was highlighting the contrast between a love of the land at a critical period in history when a climate crisis worsened the Depression in the Midwest, and how Native Americans, the Sioux tribe, treated the land as sacred yet look at how their children were treated at boarding schools. It has been a while since I read the novel, so I wish I’d thought about it back then. Thanks for sharing your views.

Other readers are welcome to share their thoughts about the title/theme, if you see these comments. Thanks for reading.