Connecting four female characters to one unique place over sixty years (Las Vegas, 1957–present): You know a novelist has created compelling characters whose stories you care about when you close the last page with tears in your eyes.

Connecting four female characters to one unique place over sixty years (Las Vegas, 1957–present): You know a novelist has created compelling characters whose stories you care about when you close the last page with tears in your eyes.

’Round Midnight is a heartfelt novel deftly tied to a strong sense of time and place. The emotional highs and lows of the lives of four very different women over a span of sixty years cleverly parallel the booms and busts of Las Vegas by Las Vegas author Laura McBride, her second novel set here.

Write what you know is lyrically on display as Vegas looms as large as the characters. Like them, it bears secrets, good times and bad, fortunes and mistakes – “pain and glory.”

“Vegas wasn’t for the weak and it wasn’t for the cowardly,” McBride tells us. So you’d rightly expect her women aren’t cowards. Take June, for example. Her chapter, the first, opens with the grabbing line: “To celebrate victory in Europe, June Stein dove headfirst off the Haverstraw Bridge.”

That’s just one of many literary hooks that keeps us turning pages. Actually, by the time you’ve read the back cover you’re already hooked by McBride’s summing up her four women with catchy phrases that make us curious about them, and how they interconnect, collide. For they must, we assume, as this is not a short story collection, rather a novel with a lot going on above and beneath the surface. So we start off with June cast as “The One Who Falls in Love;” Honorata “The One Who Gets Lucky;” Coral “The One Who Keeps Hoping;” and Engracia “The One Whose Heart is Broken.”

Next come the hooks beautifully composed in tantalizing Prologues, with an alluring clue or tidbit planted. If you read too fast, you might miss these. In June’s case, it’s the mentioning of a “fateful night.” Honorata’s overture follows, misleading us with a tip that she won over a million dollars at a Megabucks slot machine so we think her life will be charmed but take notice for she also “could almost smell the sadness in the place.” All the money in the world can’t make up for what she endures.

On the surface, a nightclub is the nexus to all four women. Each of their chapters opens there, at different time periods. Their kinship, though, is more profound, which is why the novel is so arresting.

’Round Midnight opens in the late fifties in The Midnight Room; it’s a presence until 2010 when renamed the Midnight Café, a nod to Vegas’ severe economic downturn. Attached to a casino/hotel owned by June (and her husband Del) that’s fictional, yet McBride’s Vegas is inspired by history. Since June is introduced first, we follow her the longest, from her late twenties to her eighties. With its “pin-up feel,” the El Capitan was never one of the newer, flashier hotels on the Strip but when Del bought and remodeled it and June had the vision for its success, gambling wasn’t the only game in town. Entertainment was.

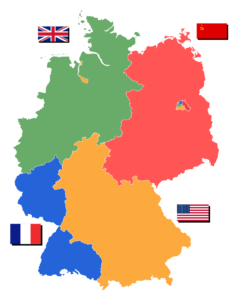

It was June’s idea, a gutsy move, to hire Eddie Knox, an exotic black singer fresh from Alabama. He’s a prime illustration of how the real Vegas is woven into the characters’ stories. Vegas was known as the “Mississippi of the West,” a hotbed of racism until 1961 when the casinos and hotels became fully integrated. Big name black entertainers like Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Sammy Davis Jr. and others may have performed there back then but that’s about all they could do alongside whites. The “Moulin Rouge pact” is mentioned: the only casino/hotel integrated at the time June sought Eddie out. We like all of McBride’s women. June, a white Jewish girl from New Jersey, warms our heart with her lack of prejudice.

June symbolizes so many “young and old, wanting to start a new life” in Vegas. She not only sensed “Las Vegas as the future,” but that “casinos were all about people and how many hours you could keep them in your joint.” So she, Del, and later their son Marshall, all enjoy business prosperity, but there’s an undercurrent of emotional unraveling that pervades.

Coral, a black music teacher, is the character native to Vegas, although we meet her after she’s come back home from California to live with her sweet Mama Augusta after her marriage ended in divorce. By then, her father had died and her siblings were gone. Back in her childhood home, she’s flooded with memories as early as seven when she’s first asked about her “caramel” skin and overhears something whispered at home. In scenes of togetherness over the years, we see a wonderfully loving family but Coral’s uncertainty about where she comes from poignantly shows us how deeply ingrained and deeply felt our identity is.

Honorata is Filipino. She makes her way to Vegas as a mail-order bride to a repulsive Jimbo. Launching her character in 1992 is a keen choice of timeframe as the Philippines enacted a law in the 1990s against this practice. Presumably, illegal schemes persisted. Since her uncle made the arrangements, her story begins with betrayal, and worsens.

Engracia is Hispanic, an illegal immigrant from Mexico. She’s the mother of a ten-year-old son, “perfect” Diego; her husband Juan is in jail back home. She’s a waitress and a housekeeper in her twenties, but her actions manifest as someone much older.

As it turns out, Engracia’s heart is not the only one broken. All McBride’s women experience heartbreak, for different reasons. And yet, the novel also sends the message that “joy was possible even if there was also a great deal of pain.” Yes, there’s the love and pain of marriage or the longing to be. But it’s the joys and heartache of motherhood – being a mother, doing whatever it takes to protect your child, the bond between mother and child, yearning for your mother – that transcends. The commonality of the women’s emotions, and how the choices they made in a fleeting moment had such lasting consequences is what makes this novel rise above.

Las Vegas was, and is, one of the fasting growing cities in the U.S. While we can watch videos of vintage versus contemporary Vegas and, of course, visit its attractions, if you want an authentic feel for Vegas through the decades, ’Round Midnight gives us that and more.

Las Vegas then

Las Vegas now

Drive outside of Vegas and you can still find the “barren earth,” the “rock and hill and sky,” and a “million mysterious stars above” that Coral is nostalgic for. But the mysteries evoked in McBride’s Vegas aren’t earthly, they’re man-made. Each of her women harbor mysteries. The one that may affect you the most isn’t even resolved until the final page. Still, the greatest mystery, the elusive one, is how an author can weave a tale that makes us cry.

Lorraine