German complicity in Nazi Germany and the German Resistance Movement (1938 to 1950, also pre-WWII & 1991 in flashbacks and endings; mostly German towns): Entire fields in philosophy and psychology are devoted to the complex study of morality. In The Women in the Castle, Jessica Shattuck is laser-focused on the moral legacy of ordinary German citizens who were complicit in one way or another as Hitler’s Nazi regime committed atrocities against humanity. Moral questions leap out from practically every page.

That’s because this is a profoundly personal novel. Shattuck is of German ancestry and her beloved grandmother (who lived until almost 100) was a member of the Nazi party. Reckoning with that agonizing incongruity makes for a most unusual, penetrating, and timely WWII novel that begs for an overarching moral code in national political discourse and conduct.

What does it mean to say someone has a moral compass? Can immoral behavior be justified to survive? Or, is there “a right and a wrong in every situation”? What if you only “half-knew” something was horrific? What if you were unobservant or too self-involved or allowed yourself to be deceived? How far should accountability go if you participated in one of the many ideological and militaristic child-molding programs of Hitler’s Youth Movement like the types characters in the novel did – older boys groups (Jugend), older girls groups (BDM), rural youth camps (“children-to-the-land-programs”) – even if you entered unaware? What about the stigma of having been reared in a “Children’s Home” for Germanisation? The abuse and scarring of children burns throughout.

Tackling these moral questions is a minefield. Not everything is black or white and nothing is easy to swallow. It’s not meant to be. Questions that have gnawed at Shattuck for it appears at least twenty years when she first interviewed her grandmother at her farm in Germany; and imaginably with much angst during the seven years she researched (extensively) and wrote this chilling novel (her third.) Questions weighing on the author for what must feel like a lifetime. Questions that should weigh on us too. These are dark times.

So it follows then that the prose feels like the author poured herself into the novel. Many sentences flow in a manner of deep absorption like the concentration Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes in his theory on the science of mental flow, examined more pointedly as it pertains to the writing process in Writing in Flow. As such, Shattuck’s prose is as clear and as dogged and take-charge as the novel’s moral conscience, conceived in a character of “unflappable strength”: Marianne von Lingelfels.

On the night of the Kristallnacht (Night of the Broken Glass, when 30,000 Jews were rounded up and sent to concentration camps), thirty-one-year-old Marianne is preparing for a harvest party at a forsaken Bavarian castle. The fortress belongs to a countess, the great aunt of her husband Albrecht, a diplomat in the Foreign Office. The countess is Marianne’s role model for she’s a broad-minded intellect, outspoken even today from her wheelchair. Which is why Marianne has taken on the herculean task of divining an “anarchic, un-German atmosphere” in a country immersed in a “wave of rigid and peevish militancy.” The first of many daunting challenges rock-solid Marianne pulls off.

It’s at this fateful party that the infamous July 20th 1944 assassination plot against Hitler was hatched. Among the guests in on the conspiracy are Marianne’s cherished childhood friend, Connie Fledermann. Handsome, charismatic, impulsive, and a “passionate champion of what he felt was right,” the opposite of Marianne’s cooler, more deliberative husband. She might even have married Connie if she were a softer, lighthearted, prettier, sexier version of herself, feelings apparent when he introduces her to nineteen-year-old, beautiful Benita he plans to marry. Marianne is her opposite: “stern-faced,” could care less about how she looks and dresses, well-educated, and politically-minded. She and Connie see eye-to-eye on important things: Germany has become a “savage land.”

In history’s real assassination attempt, the resisters included Claus von Stauffenberg and Ludwig Beck (both mentioned), and others. In Shattuck’s rendering Connie is one of those others. Albrecht was in on the conversations but he had mixed feelings, believing justice would prevail.

“There are thinkers and there are actors,” Albrecht says. Albrecht’s the thinker, Connie’s the doer, and Marianne is both. Her character is ideal for carrying out the novel’s plot: a promise she made to Connie at the party that she’d “be the commander of wives and children” should the co-conspirators’ scheme go awry, which, tragically, we know it did. This all happens in the Prologue.

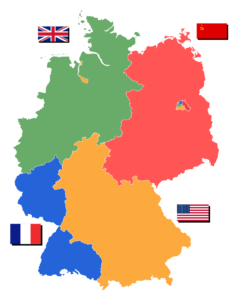

The reader, then, is prepared for Part I when it opens. Not only are Connie and Albrecht dead but “Germany itself was dead, and half of the people at the party were either killed, destroyed by shame, or somewhere between the two.” Marianne is left a widow with three children (Elisabeth, Katrina, Fritz) holing up in a few rooms of the antiquated castle she’s now inherited, protected due to her aristocratic status and the fact that the castle, located in Ehrenheim, sits within the American Occupation Zone. She is, though, surrounded by a town of fervent Nazis and later the Russians come.

Occupation Zones, 1945

By glglgl [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

The most emotional salvation is, understandably, Connie’s Benita and Martin, the son she was pregnant with when Marianne met her at the party. Benita is the spitting image of Nazi Aryan racial adoration but when Marianne liberates her she’s a shell of her former alluring, flirtatious self. Martin, the first she extricates, is also traumatized. The other emancipated widow Marianne knows even less about, the wife of the man who announced Kristallnacht at the party. Ania is “unreadable” until the latter portion of the novel when her hard backstory comes to life. Her two boys, Wolfgang and Anselm, are like her: “silent and knowing.” Everyone bears unspoken, harrowing pasts. Had Marianne known of these, perhaps her relationships and actions would have turned out differently. As the novel moves back and forth in time, place, and character we see how stark class differences and circumstances influenced who these people were when they came together at the castle. Not meant to excuse, but to help understand.

Shattuck explains how her three women are connected:

“Connected not through allegiance to any group or party or particular way of thinking but through the reality of the moment, through their shared will to get through the next hours, the next day, and the one afterward, and through their shared determination to keep their children safe.”

Despite the novel’s soberness, two uplifting scenes stood out. One takes place on Christmas day when the castle folk and townsfolk attend mass. The priest’s sermon falls hollow on battered souls. But music, Beethoven’s 9th, has the power to stir; Marianne is wondrous at how such a delicate instrument like the violin was salvaged amongst all the ugliness. In those ephemeral moments, the churchgoers felt “invited to be a small piece of eternity.” This is not about forgiveness, but the preciousness of all human life.

The other scene involves a willow tree, a leftover from a time when the ground in Dortmund (the town Ania’s from) was marshy. The weeping willow tree – “it’s bent, grief-stricken shape is a product of its longing” – serves as a metaphor for the horrors of the Holocaust. It endures yet it weeps.

Lorraine

Hi Lorraine, I’ve read several wonderful reviews of this book, but I wasn’t aware of the author’s personal connection with the story. I’m always intrigued to learn how authors relate to the story they create. I think I’ll be reading this one very soon. -Jackie

Hi Jackie,

If, after reading, you’re up for another Holocaust novel, LILAC GIRLS is an impressive follow-up and offers an interesting perspective on how two novelists take on what happened in 1939 and later. LILAC GIRLS is more explicit about explaining historical references, whereas THE WOMEN IN THE CASTLE weaves it in. Both are heavy, of course, so reading sooner rather than later when a beachy mindset might set in — seems to be that way for me, anyway — during the summer might be advised! Thanks, as always, for your thoughtful comments. Lorraine

Wonderful review. I am reading the book and love it. Your review has helped me to consolidate my thoughts.

Hi Ilene,

Thanks for writing (and signing up!) Your comment brings a smile as it’s a pleasure to know you found the review helpful. WOMEN IN THE CASTLE pierces in moral anguish, making it memorable in a way other WWII novels may not. Though the number of exceptional novels set during the war being published is striking. Hope you find some more here. Lorraine

I am reading now and your back story makes this book even better. Thanks fir enlightening me Lorraine.

Hi Barbara — Appreciate your writing, and sharing that knowing about an author’s inspiration for their book, or a theme that runs through it, also matters for the reader.

Reading, and sharing special books feels urgent during these hunkered down times. Thanks, and take care.