Beating the odds against a remarkably traumatic childhood (late 1970s to present-day; California and Oregon): Are there enough words to describe a severely deprived childhood marked by abandonment, abuse, addiction, mental illness?

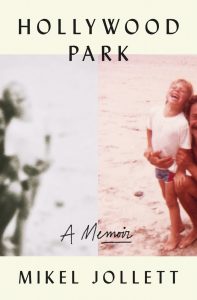

Yes it seems if every word is on fire. The kind of literary firepower Indie rock songwriter/musician-turned-author Mikel Jollett has penned in his exquisitely aching and written memoir, Hollywood Park.

Now 45, Jollett’s prose feels like he poured every ounce of his being and musicality into unmasking his story, after spending two-plus decades hiding behind “masks.” Hiding terribly pained, lonely, ashamed feelings.

You don’t need a major scientific study – the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study – to tell you traumatic childhoods can kill 70% of its victims. Jollett’s miraculous survivalist story bemoans that loudly.

For the fullest experience, you may also want to listen to his sixth album also named Hollywood Park, produced to accompany his memoir. You’ll hear the same rhythmic force and poignant voice in the music and lyrics embedded in his awesome prose. (Note: the horse-racing and running imagery highlight pursuits that profoundly affected him):

More than an outstanding memoir/album combo, the book reads like a real-life enactment of abnormal and child psychology texts, and why mental illness and addiction are toxic to an entire family.

Toxic is this review’s word of choice since it’s also central to the name of the rock band Jollett founded in LA – The Airborne Toxic Event. Considered alternative rock, the genre is more eclectic, original, or challenging than traditional rock. Mixing guitars, keyboards, drums, violins, and cello gives the music a distinctive, pleasing quality. Hear it again in Jollett’s breakout song, Sometime Around Midnight, written one particularly emotionally devastating night after he broke up with his girlfriend, when he admitted to himself he had a serious issue committing to relationships. One of many excruciating coming-of-age literary scenes. “Music makes me feel like I belong somewhere,” says Jollett:

The band’s name references part of Don DeLillo’s National Award-winning novel White Noise, in which a character, Jollett tells us, was “exposed to an enormous toxic cloud.” Precisely what his “ping-pong ball” life was like. We know that the moment we read this emotionally piercing opening paragraph:

“We were never young. We were just too afraid of ourselves. No one told us who we were or what we were or where all our parents went. They would arrive like ghosts, visiting us for a morning, an afternoon. They would sit with us, or walk around the grounds, to laugh or cry or toss us in the air while we screamed. Then they’d disappear again, for weeks, for months, for years, leaving us alone with our memories and dreams, our questions and confusion, the wide-open places we were free to run like wild horses in the night.”

Synanon – a notorious commune – once sat on the grounds spoken of. Initially a drug-rehabilitation “live off the grid” experiment, it ended up as one of the most violent cults in American history.

Synanon is where Jollett’s trauma begins. Forget freedom, utopia. Heads of children and their parents who came there to be saved were shaved, then their children were ripped away at six months of age under some perverse notion they were “children of the universe.” Raised by other women on the commune, the memoir opens when Mikel is five, his brother Tony seven. Age differences and temperaments make a huge difference in how their stories play out. Their father an ex-con addicted to heroin and alcohol; their mother an alcoholic (like hers) with a very distorted view of motherhood and family.

Mikel is the gentle, wanting-to-please child; Tony the angry, inconsolable one. Mikel bonded with childless, good-hearted Bonnie, the closest he ever came to having a real mother; Tony attached to no one. Their drama begins when their birth mother sneaks them out of the commune in the dead of the night, telling Mikel and Tony to call her “Mom,” an empty word regarding her. She’s a tormenting broken record repeating everything will be alright, nothing to fear as she’s rescued them.

Nothing is ever right, and fear is ever-present. Fear they’ll be caught by the commune searching for them. Fear of being alone. Fear of a mother who brainwashed Mikel into believing “a son’s job is to take care of his mother.” Amazing how imprinted that twisted message was for years, thinking all mothers treated their children the same.

Divided into four parts, running away from the commune is Part I, Escape. Part II, Oregon, specifically a “white trash corridor of northeast Salem,” is where they soon land. Their father has escaped too, but to LA with Bonnie detailed in California, Part III. Oregon is where more fears set in. “Mom” sees herself as the victim, never her children. Pits “Superchild” Mikel against “Scapegoat” Tony. Soon, a new fear arises. Fear of two step-dads who come and go. Both are addicts. One tries his best, takes Mikel fishing and hiking but his fate terrifies; the other is despicable, physically abusive, and forces Mikel to butcher rabbits he’s raising in a barn alongside their ramshackle house. Mikel is haunted by the violence; Tony refuses to touch the food. Dinner is a nightmarish event day after hungry day. No memories of comfort food in this bizarre, chaotic house.

Mikel tries heartbreakingly hard to keep the peace, mothering his mother under her “special child” expectations, bearing the brunt of her psychological dependency and disease. Tony becomes a bad influence on Mikel, but it takes years for him to also descend on a downward trajectory.

Mikel is a precocious child and avid reader, far more advanced than others his age. Even when Jollett relives part of his story from a child’s perspective, it’s clear to others and us he’s well-beyond his years. Infusing enough misspelled words, questions, and immature thoughts helps him sound young. Sadly, we know he never felt young.

In elementary school, he’s placed in a Gifted and Talented Program rather than skip grades. While there’s a realistic, thoughtful debate as how best to challenge highly intelligent, formative minds, his mother ignores the school’s recommendation deciding without giving it much thought believing she’s the expert!

Bouncing back and forth between two very different worlds in two different states, the California chapters are the author’s happiest. Wonderfully, Bonnie is still with their father, and he truly wants to be a father. Bonnie’s Jewish family opens their arms to Mikel and he enters junior high school there. Viewed as betrayal by his self-consumed, guilt-inflicting, deteriorating mother whose working at an Oregon mental hospital with prisoners teaching group therapy! Astounding when she’s grossly failed to nurture her own group/family.

Junior high is a fascinating period from the standpoint of the author sensing belongingness. Bused into a school where he’s the racial minority, he relates to disadvantaged kids who’ve been victimized too. In high school, he desperately tries to fit in, discovers long-distance running, which becomes obsessive on the track team at Stanford University, where he’s accepted on a scholarship. Dream come true? Not when you’re an outsider among the elitist crowd.

College is included in Part IV, Hollywood Park, named after the racetrack Jollett and his father spent so many good times together. Bottled up angst propels his music, learning how to “make the pain useful.”

After his father’s death, Jollett poured his heart out in his memoir. A testament to appreciating he’d been “just broken enough to see beauty.”

Lorraine