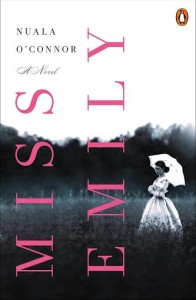

A poet’s voice and humanity (Amherst, MA and Dublin, Ireland, 1866): For a blog called Enchanted Prose, Miss Emily is a literary standout.

A poet’s voice and humanity (Amherst, MA and Dublin, Ireland, 1866): For a blog called Enchanted Prose, Miss Emily is a literary standout.

Irish poet/author Nuala O’Connor’s artful American debut about the reclusive Victorian poetess, Emily Dickinson, is packed with poetic prose (“I am an eyeglass in the eyrie.”) From a writerly point-of-view, it also shines because of the attention paid to the solitary craft of writing (the “writer’s absolute need for quiet and retreat”); the importance of words (“words are my sustenance”); and the uniqueness of words (“each word solitary”). “Chimerical, perplexing, beautiful words” please her – and us.

This slender novel delivers a strong punch by packing in so much poetic prose the reader hears Emily’s tender voice, feels her unconventional spirit, senses her impassioned soul. It starts off reposeful, then intensifies, answering affirmatively to a question Emily poses: “Can calmness and energy be bedfellows?”

Short chapters, with titles written in “inked curlicues” suggestive of Emily, move back and forth between Emily’s voice and a second female’s: fictional Irish maid, Ada Concannon, 18 years old and newly immigrated from Dublin, Ireland. Ada finds work at the Dickinson’s home, Homestead, in Amherst, Massachusetts, “a town of light and brick.” Ada is made up but she’s true to the historical record, as the largest source of American housemaids in the 19th century hailed from Ireland. Ada allows O’Connor to softly transport Ireland to America for readers, pointing out the “openness” of Dubliners compared to the tight-lipped nature of New Englanders. (There’s “no better secret-keeper than a Dickinson.”) Ada also provides a vehicle for airing prejudices against the Irish. Emily befriends and defends her, a caring friendship disapproved by her family, most notably her brother Austin, who cautions “all Irish people lie” and are melancholy.

Emily Dickinson’s Homestead

Photo by Daderot [Public domain]

Inventing a tragedy that strikes Ada and affects a handsome Irishman she’s fallen in love with, Daniel Byrne, forces Emily to venture outside her inner sanctum (“I am in the habit of the house, and it is in the habit of me”) to help Ada and Daniel. Austin’s “detached legal mind” may disappoint Emily, but he takes risks, gets involved too. Knowing how dearly Emily Dickinson cherished her freedom and safety, her act of selflessness and kindness is extraordinary.

Miss Emily takes place over a year in Emily and Ada’s lives. We meet Emily in her late-thirties, when she’s chosen to become that “Woman in White,” dressing only in white. (“If I am pure in dress, my mind may empty itself of all concerns, and that will make it easier for me to write.”) She may be lonely (“the outside world does not bring me joy”), but her inner world (the “landscape of my invention – poem lands”) brings passion and solace.

O’Connor’s Emily instructs us not to be fooled by her singular white attire, for “inside I will roar and soar and flash with color.” And so she does, making this Emily accessible. She craves sweets and loves baking (“I love the kitchen on a dreary day”), the pleasure enhanced by Ada, who perceives even butter as “exalted.”

Besides poetry, this inwardly colorful Emily is passionate about gardening, nature, and “the only audience my heart trusts,” her sister-in-law Susan. She’s so much closer to Sweet Sue than her cat-loving, also single sister, Vinnie, content with housekeeping chores. Emily idolizes Sue. Sue may not fully understand Emily’s poetry – “I love to riddle” – but she’s so unlike Emily’s mother who “would not understand the demands of the mind,” a Victorian wife “who obeys.”

O’Connor handles Emily’s intimate affection for Sue delicately. “I love you from a distance,” Emily says. (An emotional distance as Austin’s family home, Evergreens, was so close to Emily’s the two seem almost one; both homes now living museums.) Was her love deeper than sisterly? There’s no direct suggestion although Sue (mother of two and civic-minded) expresses discomfort with Emily’s profound adoration. Still, we perceive Emily’s choice of a single life as a revolt against being “regularized.” She yearns to “pursue the things that please me,” which makes us smile knowing many things pleased cloistered Emily.

This Emily is likened to the Irish, who “put great store in spinning a narrative around every small thing.” She’s also a deep thinker, questioning the existential meanings of life. (“Each dash I create is a weight, a pause, a question.”) There’s no place for religion in Emily’s worldview, unlike devout Ada, preferring science to help explain the unexplainable.

Ada’s Irish voice brings prose that delights too. My favorite word of hers is figairy. A light, rhythmic sound, but I had no idea what it meant. It’s Irish slang for whimsical, thoughtless. The opposite of this serious, well-researched, thoughtful novel!

For all the writers who dread a white piece of paper, Emily inspires. Blankness “seduces” her. It’s also inspiring to read ordinary things expressed poetically: The snow of Amherst becomes “sugared Amherst.” Nightfall turns into “twilight fingers Amherst with its tawny glove.” Dried fruit described as “crinoline hips and the flesh of candies.”

Miss Emily inspired me to start reading a modern-day memoir about singlehood: Kate Bolick’s recently published, well-written Spinster. Bolick, an editor for The Atlantic, aspired to be a poet. Like Emily, she feels “most alive when alone.” Interestingly, her research shows that the largest group of single women in the 19th century lived in Massachusetts. Her discussion of single women moves from the derogatory to the positive: from her own “spinster wish” to a 19th century, short-lived term, “bachelor girl,” and then to Henry James’ depiction of the “New Woman.” In 1913, this woman was deemed “a very splendid sort of person.” Just like the Emily we meet in this novel.

Lorraine