Of all the long book signing lines I waited on at Book Expo America (BEA) 2014, the longest was Colm Tóibín’s, award-winning Irish author and Columbia University professor. Having read The Master and Brooklyn, I understood why.

Of all the long book signing lines I waited on at Book Expo America (BEA) 2014, the longest was Colm Tóibín’s, award-winning Irish author and Columbia University professor. Having read The Master and Brooklyn, I understood why.

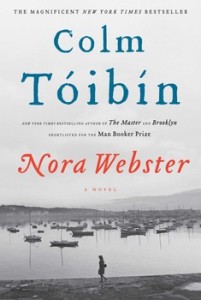

“Dignified” Grieving: Imagined and Personal (Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Ireland, 1969-1972): Colm Tóibín is a master of pitch-perfect tone. His Henry James novel, The Master, is elegant, atmospheric prose evoking the 19th century period. In Brooklyn, a young Irish woman’s coming-to-America story – immigrating from the author’s hometown, Enniscorthy – the vibrant prose befits an innocent’s experience in lively Brooklyn in the 1950s. In Nora Webster, Tóibín ages the unworldly Irish woman, places her back in Enniscorthy, where the prose can slow down and fit Nora’s understated grieving. Of the three, Nora’s is the simplest prose, deceptively so, given all its thoughtfulness and meaning.

For Nora Webster is a complex character, intentionally so, someone who admires her sister-in-law when she “disguises her feelings.” That’s because Nora “kept silent about everything on her mind,” so she draws us right in. While there’s undertones of a range of emotions we’d expect a grieving Nora to feel – sadness, anger, guilt among them – much of the time we’re trying to figure her out, just as she is trying to figure out how to live again, having recently lost her well-liked schoolteacher husband of twenty years, Maurice.

Nora is the mother of four (two older girls, Fiona and Aine, not living at home; two younger boys, Conor and Donal, who are), who in her forties is suddenly faced without an income (money is so tight she doesn’t even own a phone) and a life that’s “oddly pointless and confusing.” The reader should note that Donal, the older son, is twelve – the same age Colm Tóibín was when he lost his father. No wonder this fiction feels so real.

Still, in another writer’s hands, Nora’s three-year journey of quiet grieving – hiding and controlling her emotions – while going about the ordinary business of living might not be so riveting. Because she’s closeted, emotionally complex yet authentic, she fascinates us. We really want to know what happens to her. And so, what’s ordinary becomes extraordinary.

Baginbun Bay, County Wexford, Ireland

(Humphrey Bolton [CC-BY-SA-2.0],

via Wikimedia Commons)

Donal appears to be most at-risk. His emotional pain is visible. Since his father died, he has developed a stuttering problem. Note: this detail is autobiographical too. So is the fact that Tóibín’s father was also an admired schoolteacher, and, like Donal’s father and his brother Jim, active members of Fianna Fáil, Ireland’s conservative Republican Party. (One of several political overtones. Violence in Northern Ireland another.)

While you might judge Nora an uncaring mother – “it was strange, she thought, that she had never before put a single thought into whether they were happy or not, or tried to guess what they were thinking” – when something egregious happens to Conor at school (which would never have happened if Maurice were alive having taught there), she’s nothing but fierce, determined, and extremely effective. Best of all, here, Nora doesn’t care what anyone thinks!

Worrying about what others think in a community where everyone knows your business is a recurring theme intruding on intensely private Nora. When we first meet her, she’s weary of all the good-natured characters constantly stopping by her home, unannounced, to pay their condolences – a “hectoring tone” that she “tried to understand that it was shorthand for kindness.” Two of those well-intentioned visitors Nora welcomes the most are her brother- and sister-in-law. They help her get her footing financially, circumstances that improve over time in part due to her rising widow’s pension – another political issue that offers a window into Ireland’s social reforms, and another aspect of the novel that rings true for the author.

If, like me, you haven’t traveled to the towns and villages dotting the southeastern coast of Ireland – names like Blackwater, Bunclody, Curracloe, Ballyconnigar, Ballyvaloo – places Nora’s outings take us to, you might want to glimpse images of what Nora’s world looks like, to better picture her. Photos of beauty and solitude beg the question: Why didn’t the landscape give Nora the kind of peacefulness and privacy she craves? The answer, I think: Too many memories.

That’s why Nora’s so willing to so quickly dispose of the family’s summer home in Cush, without even consulting her family, one of the first bold steps Nora takes early on. It gives us clues into her strength, her love, and her pragmatism. She does not want to hold onto these memories. She may be “surprised” by “the harshness of her resolve, how easy it seemed to turn her back on what she had loved,” but she’s a realist. “This was the past then … it cannot be rescued.”

Ballinesker Beach, County Wexford, Ireland

(Michal Osmenda [CC-BY-SA-2.0],

via Wikimedia Commons)

When she’s forced to return to a job she held so long ago that she never imagined she’d have to go back to, where she must also endure the wrath of a bitingly unpleasant supervisor, an ex-friend she hasn’t spoken to in over twenty years, she reminisces on her lost freedom but, as for what should be her greatest loss, she never explicitly tells us she misses Maurice. She reflects that it was a “life of ease,” but one “that included duty.” Was it duty to her husband and/or to her children she laments? One of her sisters remarked that, after Maurice, Nora changed from a “demon” to “meek.” Was she his shadow because she preferred it that way? Or, because everyone gravitated to him? We’re not entirely sure.

Sometimes, Nora reveals herself at the cusp of being a more modern woman, if only she knew how. Again, the historical backdrop matters. This is the end of the sixties. Nora may not be a self-proclaimed feminist, but she seems proud of her daughter, Fiona, doing her teacher training in Dublin, and for getting mixed up in the cause of the city’s slum housing. When Fiona disappears for a few days after riots broke out there, others are frightened but Nora remains calm and resolute that Fiona will be okay.

Nora shows us that she’s open to change and in some ways feels freer – dying her hair, taking singing lessons, joining the Gramophone Society, buying a record player and albums, redecorating, going on a trip to Spain with her Aunt Josie– but these try-outs don’t necessarily go smoothly. To her credit, she agrees to participate in things, but mostly she’s not interested in them, has regrets, or worries that people will think she’s “lost her mind” or been “extravagant.”

As in real life, some things naturally lead to another, gradually moving Nora along. In her grieving process, she wonders what her life might have been like had she been born elsewhere? Without responsibilities? She may have lived a conventional life, but Nora has dreams. Did she always have dreams, or has her new situation given her an opening to dream? Again, we’re not entirely sure.

What we do know is that Nora Webster wishes to be transported away from the “dullness of her own days” to a “dream-life.” What that “dream-life” is we cannot say. What we can say is that music is where she finds the space to dream. Music sets her free. Drifting softly, not loudly.

Lorraine

Lovely review, Lorraine. I remember waiting on the line at BEA to meet Colm Toibin. I’ve been looking forward to reading this novel — even more so now that I’ve read your review.

FYI – The film adaptation for Brooklyn releases at the end of January. It was written by Nick Hornby.

Hi Jackie,

Funny how memorable that particular line was! Maybe it was also meeting you. Didn’t know about the Brooklyn film adaptation. Haven’t read any Nick Nornby, but maybe I should now. Thanks for writing. Happy New Year, and I look forward to seeing you in 2015 someplace, sometime at BEA. Lorraine

Lorraine, I just finished the book! I had to write again, if only to say how spot on your review is. I really marvel how Tóibín is able to create such wonderfully complex but subtle plots.

I love that you pointed out the uncertainties we readers are left with. For example: “Was she his shadow because she preferred it that way? Or, because everyone gravitated to him? We’re not entirely sure.” This perfectly mirrors real life. Sometimes things aren’t cut and dried. He’s able to convey the possibility of either option and then leave it up to you to decide.

I thought it was marvelous! And you wrote a marvelous review!

Hi Jackie,

Happy to know you really enjoyed it, so nuanced, and that we saw it the same way. Your comments mean a lot to me, so thanks for writing.