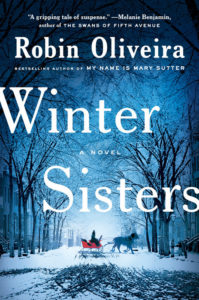

Dedicated to “girls and women everywhere” – Profiles in courage and compassion for the ages (Albany, New York; March to June 1879): Eight years ago, we came to know Robin Oliveira’s indomitable Mary Sutter, a civil war nurse who lifted our spirits in the face of medical horrors and prejudice against female doctoring. For all Oliveira’s fans (I’m one of them) clamoring for a sequel: Mary is back!

Dedicated to “girls and women everywhere” – Profiles in courage and compassion for the ages (Albany, New York; March to June 1879): Eight years ago, we came to know Robin Oliveira’s indomitable Mary Sutter, a civil war nurse who lifted our spirits in the face of medical horrors and prejudice against female doctoring. For all Oliveira’s fans (I’m one of them) clamoring for a sequel: Mary is back!

This time she’s waging a different kind of war, perhaps “more sinister than the brutality of artillery.” Fought on several fronts, this war is more intractable and less visible, defying a repressive old guard class system and heinous behaviors.

A war that calls for Mary to return to continue to fight for the rights of women, young and old, from all walks of life. A war that threatens to risk her reputation. Now a physician for the past twelve years, yet still fighting negative attitudes toward women in the profession as she ministers to marginalized women hospitals refuse to treat: prostitutes. This Mary’s primary fight though revolves around two innocent girls unprotected by a horrendously backward legal system.

Winter Sisters is layered and entangled. It also links to the emotional abuse of high-society women married to powerful men who treat them like servants or worse. Wealthy yet impoverished, a “life without agency” anathema to Mary.

A tall order! Though Mary is up to the task, she’s not the only champion. Others are also women, with one shining exception: a charming, young gentlemen. They are the brightness in this tale of darkness.

The novel’s setting and historical timeframe are key to the plotting and richness of the prose. Winter Sisters takes place in Albany over 112 days (you’ll see why that number matters) in 1879. In 1888, Albany and the entire East Coast were dealt a monster blizzard, known as the Great Blizzard or the Great White Hurricane of 1888. Albany received something like 45 inches of snow. Hundreds of people perished, like the parents of the titular two winter sisters.

In the opening sentence, we’re told Emma and Claire O’Donnell have vanished. For six torturous weeks and plenty of suspense no one has seen or heard from the “blizzard girls” as they infamously came to be known. They are presumed dead.

“The mystery of their whereabouts had become a question of sport, debated with passion in every tavern, prayer circle, factory, horsecar, railroad depot, restaurant, brewery, shop, and home.”

The author once called Albany home. It shows. Her regard for it’s fierce weather, stately Victorian architecture, and the impact of the Hudson River and Erie Canal on commerce and livelihoods is richly depicted.

The trade featured in the plot relying on navigable waterways is the lumber business. Gerritt Van der Meer is a lumber baron. His shy wife Viola is the dejected, lonely socialite. Their son, Jakob, twenty-one, is the gentleman of honor mentioned above. Gerritt is a selfish, condescending brute to Viola, whom Jakob is devoted to. A Harvard lawyer who gave in to his overbearing father’s familial demands to help run the business, which comes at great professional and personal sacrifice when he falls smitten with beautiful Elizabeth, Mary’s seventeen-year-old niece, a violin prodigy.

The beauty of music as a soothing, healing antidote to the sordid story (the author doesn’t flinch, again, in describing hard-to-stomach medical details; she was a critical care nurse) involving the two sisters. “Beauty and horror always met side by side.”

Oliveira chose a year after the real historical blizzard to set her third historical novel (I Always Loved You is a gorgeous tale about the passionate artist Mary Cassatt) because of a law on the books she discovered (impressive research her brand) that screamed out for Mary’s mettle. For her “perseverance and courage and dedication.”

That law is key to Emma and Claire’s story, something readers must find out about for themselves. Sorry to be cryptic, but you wouldn’t want me to spoil the mystery. You’ll learn what happens to them soon enough, about a hundred pages in at the end of Book One. Given this is a 400 page novel, Oliveira’s longest, and you have two more parts to go, clearly it’s not a straightforward mystery. The novelist’s imagination doesn’t work that way.

In this atmospheric historical timepiece, she immerses us in a “city of graft,” corrupt not only in its business dealings but in the morality of its conduct regarding girls and women.

Prostitution was big business in those bygone days. One, Darlene, whom Mary tends to at her frowned upon clinic, will tug at your heart for she does good here.

Other do-gooders include some characters reintroduced from My Name is Mary Sutter. Yes, this is a stand-alone novel. Even if you read the author’s award-winning debut, that was years ago. Mary is indelible but, like me, you may need some reminding about the others.

Mary is now forty and married twelve years to William Stipps, the elder civil war surgeon who can’t “breathe” without her. After all Mary went through during that war, we shouldn’t be surprised she’s “silvered.” William is an orthopedic surgeon, which makes sense after all the amputations he and Mary performed on the battlefield.

Also back is Mary’s mother Amelia, a midwife who “can make anyone feel at home,” and briefly Bonnie, Amelia’s close friend – the deceased mother of the blizzard girls. Elizabeth still lives with Mary and her mother for she’s orphaned too, reeling from the “sadness of losing everything she loved.” The “Sutter women bore up at all times,” whereas Elizabeth represents the fragility of an artist painfully unsure of herself. When the girls go missing, she flees with Amelia from Paris where she was studying at the Paris Conservatory of Music.

Deaths from war and childbirth – and now merciless weather – created “convoluted” relationships, people caring for one another as if they were family rather than looser connections and friendships. That’s the situation here. So when ten-year-old Emma and seven-year-old Claire disappear Mary, William, Amelia, and Elizabeth all go searching as if the girls were their own flesh and blood.

One of the joys in this somber story is Mary and William’s marriage. “Neither of them could think of a time together when either of them let each other down.” They don’t let us down either as they fight for justice and equality.

All of Robin Oliveira’s novels stand out for their strong feminist messaging. Winter Sisters feels like crystal-ball timing: the 19th century converging into the Me Too Movement.

Also on display and timely is the wicked “power of money” that “brought loyalty where none was deserved. It bent minds and curated behavior. It solved problems.” Greed, bribery, and betrayal also begets egregious crimes, whether a century ago or unfolding today.

Albany’s weather also wreaks havoc. After the blizzard came, mighty floods – termed freshets – that overwhelm the city, once the snow melts. The Hudson is a river of ice – floes, another meteorological term I hadn’t known. Albany is a city of bells that ring out flood warnings, though it seems nothing could stop the tragedy that ensues.

Tom Brokaw, the veteran journalist, recently predicted the 21st century will be remembered as the century of the woman. Thus, a 19th century novel makes a hard-hitting contribution to a 21st century cause.

Lorraine