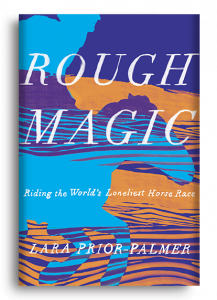

Why did she do it? How did she do it? Winning the Mongol Derby (Mongolia, 2013): Rough Magic is a stunning memoir that leaves you with more questions than you started with. Those are: Why did Lara Prior-Palmer, at nineteen, enter “on a whim” the “longest and toughest horse race in the world,” in Mongolia? How did she win it, when half of the thirty competitors from around the globe never even finished the ten-day race that Prior-Palmer completed and won in only seven days?

Mongolia is considered the most sparsely populated country in the world. Of its over three million people, 25% to 40% are nomads and herders living in gers (like a “Russian yurt”) on grasslands, the steppes. A way of life that depends on horses; a country with “more love songs about horses than about women.”

P.Lechien [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

For the British author, who splits her time between London and a small English village, Mongolia’s disorientating landscapes with “fourteen different microclimates” weren’t like anything she (or we) had known. The author is more at home in the English countryside than the “concrete nowheres” city. She’s also far more at home on a horse than with people, describing herself as someone with “a failure to emotionally engage.” Yet, she’s really not at home anywhere. “Why tie ourself to a place?” she wonders. Antithetical to so many searching-for-home memoirs.

This memoir is a search for self in spite of/regardless of place.

As for why more questions, two reasons. The writer thinks like a philosopher, constantly questioning herself and us with existential questions like: “Do you find yourself searching for the meaning of life?” She also chooses and spins her prose like a mystical poet, triggering spiritual questions. Quite fitting for an otherworldly country in East Asia that follows Buddhist and Shaman spiritual beliefs.

Both religions esteem nature. So do Mongolians who care so much about the land they wear “soft, curved soles to spare the stalks of the tiniest plants and to avoid hurting the earth.” And so does the author, who observes “we humans seem to have put a lot of energy into separating ourselves from nature.”

The Why question, then, is the easier one to answer.

To understand where the author’s mystical prose stems from consider her exotic academic pursuits. She went to Stanford University in the US, majored in two unusual subjects. One I had to look up: “conceptual history.” It explains her philosophical reflecting as this approach to understanding history and culture applies a philosophical bent. Her second major, Persian studies, includes language and culture, which accounts for references to poets, prophets, and a love for ancient history that’s “pre-concrete, pure horse.”

The author opens her memoir when she’s searching for what to do next in life, after graduating from high school and finding her au pair job in Austria claustrophobic for her restless soul.

Prior-Palmer is not someone who sees herself in flattering ways. “Simply befuddled,” a “scatterbrain,” and “ditzy” are not the characteristics you think of for surviving and accomplishing a grueling long-distance horse race with “no set route,” in vast, wild, diverse landscapes. She carried a race map, but “a map cannot lead a mind across a river.”

Perhaps dreaming does, when your dreams about “freedom and independence.” She lets us know from the outset these aspirations are very much on her mind, quoting the rough magic line from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, which she brings along with her. Freedom is an important theme in Shakespeare’s “final play, a play of dream, spirit, and sea.”

Why, then? She imagined the race would set her free.

While many questions are asked of us, much of the memoir feels like the author is talking to herself, in spare, lyrical, stream-of-consciousness prose.

Prior-Palmer began the race perceiving herself as non-competitive. When she meets one of the riders – twenty-year-old Devan from Texas, her bragging about being on the US Endurance Team irritated her greatly, stirring her. Overconfident Devan serves to motivate her, push her, intensifying as Devan was hours ahead of everyone for most of the race. “What had we all missed by not growing up in Texas?” One of her humorous, sarcastic thoughts. Even when she won, she didn’t boast, believing “overt ambition is disgraceful.”

Why, then? She was out to prove something to herself.

As to How she won, even the author can’t answer that. Woefully unprepared for endurance, cross-country riding, unlike her idol, her Aunt Lucinda. Lucinda Green is an Olympic champion in the British horse racing world. But the longest race in England couldn’t begin to compare to the Mongol Derby, designed to imitate Genghis Khan’s postal system in the 13th century, covering a mind-boggling 1000km or 620 miles!

Prior-Palmer spent only a month (others six months or more) preparing for a race that depended on her own fitness as well as horses – “horses’ hydration levels, gut sounds, lameness protocol, and heart rates.” More daunting, she had to learn to handle “semi-wild ponies” that are “rarely handled and therefore hypersensitive to human motion.” And she had to re-learn that twenty-five times. Twenty-five different horses, changing for a new horse at urtuus,“horse-changing stations.” That’s “twenty-five ponies saying Who are you? and Who are we?”

Another challenge was reaching each station (equipped with gers where the riders slept, although not always finding enough beds) by 8:30pm or you’re penalized. (Also penalized for returning a horse with an elevated heart rate.) This meant learning navigation tools as you don’t dare get lost, nor ride alone.

Enduring all of that, the author asks, as we do: “Why the need to go all that way and do such a thing?”

You don’t have to be a horse enthusiast to be moved by this provocative book. All you need is a desire to be inspired by someone who took a bold step, succeeding at something out-of-this-world. The author’s extraordinary mental fortitude belies her mother calling her a “sensitive mouse” and defies her compromised health, years of stomach aches and unknown pains, which you’ll discover are not in her head. A reason, it seems, she asks: “What gets you out of bed?”

Imagine all the calories burned riding up to fourteen rough hours a day. Then imagine consuming for breakfast just “fermented horse milk, the national drink” (if anything at all, because losing time rushes you.) Lunch not much better: noodle soup with mutton fat. Nourishment comes from the Mongolian people, welcoming and generous, giving what they can.

So many obstacles to overcome, but the author wouldn’t let anyone see her pain or fears. A very tall order given a film crew was making a documentary following the riders around, along with a TV reporter.

Fears are expressed privately in a Winnie-the-Pooh journal, a childish name but there’s wisdom in that bear and his animal friends’ words. Included in the journal are pretend letters written to the author’s mother; also notes about each horse and riding/landscape experience, which, presumably, allowed her to write vividly over the five years it took to craft her memoir.

The author’s race horses ranged from lame to slow to fast, one a “madman.” She takes to naming them. One named for the race photographer Richard Dunwoody, another observer, often snapping pictures of her. Later, she learns he was an Olympic jockey.

“What is it that horses can do for us?” One answer is that “being on a horse pulls you out of yourself and grounds you in the larger land.”

Again, we think we know Why. How remains the magical part of the Shakespearean title.

Lorraine

Pingback: Wild Horses of the Summer Sun: A Memoir of Iceland ← Enchanted Prose