Books and beaches, an intoxicating mix (Manhattan to Truro, MA, summer 1987; epilogue 1988): As the title suggests, The Last Book Party has something to do with the literary world. Zooming in on the “trifecta of literary success: talent, confidence, and connections,” this party is intoxicating.

Especially for the protagonist: twenty-five-year old Eve Rosen, aspiring to be taken seriously as a writer. Her writerly angst is relatable to all who yearn to feel valued.

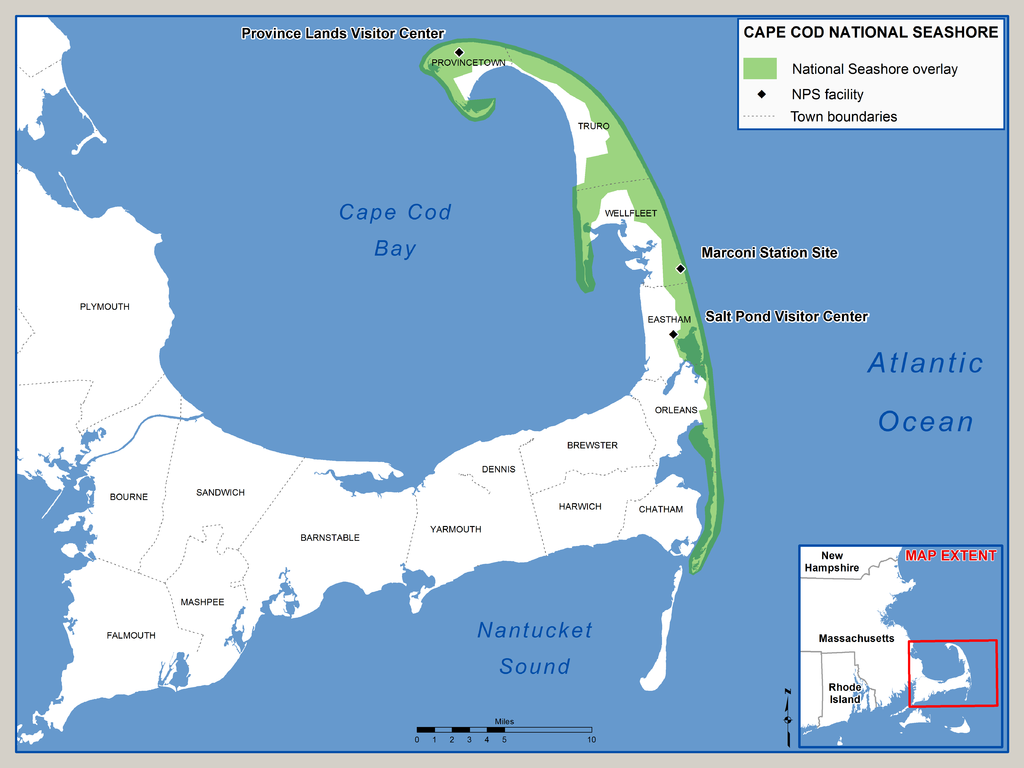

The beaches part is the setting: an idyllic, sand-duned beach town on the tip of the Cape Cod National Seashore, Truro.

By EricM [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Eve is not the only character struggling to be appreciated. But she’s the candid one, out-front about her low self-esteem.

Considering Karen Dukess has been writing speeches on gender equality for the UN Development Programme for the past eight years, the theme of empowering women is at the forefront. Not only for the late eighties timeline of the novel, but right now as the champion US Women’s Soccer Team fights for equal rights, and recently in the Women’s March and Me Too Movement, protesting the most abusive weapon of power and injustice.

So it shouldn’t come as a shocker (though it does) that in an industry filled with women producing books read mostly by women, if you’re an aspiring female writer you’re “eight times more likely to get published” if you submit your manuscript under a male pseudonym.

Getting published is not Eve’s first hurdle. What she needs more than anything else is to get into the creative zone. She hasn’t put pen to paper, typed a single world (this is the pre-Internet era), since her Brown University days, surrounded by so much talent she felt she didn’t have any. Talent being the first leg of that “trifecta,” one of many great one-liners.

As for the second leg – confidence – bookish Eve has lacked that since childhood. Her brother is a math genius; her mother doted on him, ignored and disparaged Eve, saying hurtful things like “if you’re not blessed with genius, what is the point?” Eve’s self-confidence was so deflated she thought: “How could an ordinary life like mine result in a story worth telling?”

Told in flowing prose in an ideal setting for creative, freedom-loving types, this is a delicious summertime read, bringing books, literary characters, and the super-competitive publishing world alive for book-lovers. But, there’s nothing easy or charming about the “summer elite” world Eve throws herself into.

Opening at a Manhattan publishing house, Eve jumps at the chance to leave her lowly editorial secretary job to spend a summer in Truro rising to editorial assistant to one of the “old guard” at the venerated The New Yorker magazine, Henry Grey. He needs a smart, disciplined organizer to help him finish his long-overdue memoirs. She, in turn, hopes greater “proximity to literary success” will rub off on her – the connections leg completing the “trifecta.”

Truro was something Eve had felt confident about. Her parents own a summer home there; she’s spent every summer of her life soothed there by the ocean landscape. But Henry’s Truro is not what she expected. Her conventional family followed the rules. Not exciting enough for Dukess’ “writers, editors, poets, and artists” who follow a different code.

Working alongside Henry seemed like a perfect “confidence booster.” He’d appreciated the respect and attention she gave him back in that publishing house where his memoirs were otherwise neglected (her boss Malcolm focused on up-and-coming talent.) What Eve didn’t know was “the way things appeared – or even the way people said they were – had any relationship to reality.”

What she also didn’t know, but would have been wise to have considered, was how uncomfortable she’d feel working in the same house as Henry’s bohemian wife, Tillie Sanderson. A “serious, obscure poet,” Eve had been unable to decipher her in college. Tillie treats Eve condescendingly, if at all.

Eve doesn’t seem to have any friends, so when she arrives in Truro and meets Tillie and Henry’s son, Franny, a painter who doesn’t read – an “outsider” like Eve in this made-it lit world – she feels welcomed. “Free spirited Franny” is so at ease with himself, so at “ease with which he floated his ideas,” he made her job easy to settle into. Too easy.

Later, Eve reflects on Franny’s charisma: “He made us feel lighter and freer, not like who we were but who we wanted to be.” The us includes Jeremy Grand, whose not so grand after all.

Turns out Jeremy is boss Malcolm’s new protégé, the one who has treated Henry disrespectfully. Jeremy just so happens to be Franny’s old chum from their exclusive New England boarding school days. One of a number of entangled relationships that signal things may not be as delicious as they seem.

Jeremy is the opposite of light-hearted Franny. He’s arduous and arrogant, but he gets along swell with Henry and Tillie, who treat him better than their own son. The literary world is seen as thicker than blood.

The men in the novel have formidable egos and secrets, but it’s Tillie whose the hardest nut to crack. Off-putting Tillie has her own dedicated assistant, Lane, who plays a larger role than we saw, until the surprising ending.

What we’re not surprised about is seeing that the only way Eve is going to pull herself out of her rut is to shake things up, thus shake things out. At twenty-five, this is Eve’s twists-and-turns, coming-of-age transition to adulthood.

Eve is searching for her identity, whereas Henry is grasping to hold onto his. Occasionally he dips his columnist hands in The New Yorker, but his golden years at the magazine are over. Debonair, he’s a nod to the charming gentlemen of the golden era of Hollywood who didn’t air all their emotions. He covers his up with his brand of truth-telling, “fact-heavy” journalism. Eve lets us see underneath.

Henry and Eve may be from different generations and religions – she’s Jewish (so is another character who hides it), Henry’s not, adding another dimension to the outsider theme – but they share a love for the “same novels, the same characters, even the same lines.” Discovering a like-minded reader can connect people in powerful ways.

The novel could be dedicated to all the women who have borne the brunt of not feeling special, who’ve been blinded by their desires to feel special.

Eve’s father is the quietest character, but when his voice pops up its to give wisdom so his daughter might feel happier about herself. “I never wanted a big life,” he tells Eve. Who replies: “You wanted a small life?” No, he says, “I wanted a good life.”

These may sound like simple words, but the underlying premise is not. Especially in an extremely ambitious society willing to leave so many behind.

Lorraine