Fashion as a reflection of history and nationalism (pre-WWII Paris, 1938-1940; 1940s-1954 Manhattan, with a post-war return to Paris): The high-fashion industry or haute couture is so much more than meets the eye in Jeanne Mackin’s newest historical novel set mostly in Paris in the years leading up to Hitler’s invasion of this colorful city, blackening it. Color – or the lack of it – is key to the story and the refined prose that effortlessly blends fiction with engaging historical details, Mackin’s trademark (see The Beautiful American and A Lady of Good Family).

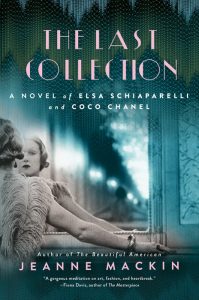

In The Last Collection, Mackin adeptly takes advantage of the rivalry and stark differences between two leading fashion designers of the 20th century – Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli – whose clothing styles, personalities, and ideologies captured the conflicted moods and political climate in the lead-up to the Paris Occupation.

Ironic how Coco Chanel is still fabulously known for her elegant, smart black-and-white designs, whereas Schiap (as her friends called her; cool, intimidating Coco essentially friendless) is barely known outside fashion circles, though considered the more innovative and artistic. Her flamboyant-often-bordering-on-“bizarre” creations inspired by her friendships with Surrealist artists like Salvador Dali.

Elsa is the designer we come to admire. Generous, fun-loving, bold, and openly anti-fascist (though pro-Communist), she refused to cuddle up with the Nazis like Coco, a Nazi sympathizer and mistress, later revealed to be a spy. Two larger-than-life women who couldn’t be more opposite, yet both “very driven” and “very successful.” They left their marks on fashion, also “politics. And of course, love. The three primaries, like the primary colors.”

Those colors – blue, red, and yellow – form the novel’s three parts. One-page prologues introduce each part’s titled color, defined emotionally and historically. Mackin understands color so keenly you’ll wonder if she’s also a painter like her primary character, Lily.

Lily is the fictional go-between the real Schiap and Coco. She sets an overall melancholy tone to the prose, befitting those complicated times.

Blue defines Part I, “the most suggestive of paradox.” Despite impending war, late 1930s Paris was still holding onto its joie de vivre, seen in the legendary cafes, dance clubs, parties, follies, balls. People were ignoring or denying what was swirling around them as Germany invaded Poland, then Czechoslovakia. Mackin’s finely-tuned prose is remarkably disciplined. She doesn’t overwrite gay Paris, as a dark cloud was moving toward the City of Light.

Paris, then, is painted as a conflicted city, like Blue, the “color of longing and sadness, and yet it is also the the color of joy and fulfillment.” Lily personifies the sad, longing, nostalgic shade of blue, though Paris eventually re-awakens her.

The prose stays honed-in, even in Part II, Red, the unequivocal “color of love and passion” because red also means blood. So we continue to feel the uncertainty, anxiety, protracted waiting despite the happiness characters find as the onslaught is coming.

Part III, Yellow, is a color that warns and cries for help as fear bubbles to the surface. Defined also as the color of the Star of David Jews were forced to wear to separate them, determine their fate, the angst bursts as war descends on Paris.

Characters exemplify colors and themes. Like Paris, they’re also conflicted, complicated, entangled:

Lily: 1954 Lily opens the novel. She’s forty, working at the Manhattan gallery of a tremendously important art dealer, Paul Rosenberg, one of the Jewish characters. He (and his family) saved precious art stolen by the Nazis. Late 1930s Lily comes to know him in Paris, after she leaves a dreary existence in England teaching art to girls with compromised health at a boarding school her brother-in-law, a doctor, also works. Begrudgingly, he helped Lily get back on her feet securing her the job; no familial love as he blames her for the death of his brother, Allen. Lily accepts his scorn as she cannot forgive herself either for her role in some kind of an accident. You’ll learn what it is, later reminding us of the tremendous bravery of people during wartime.

Lily’s grief, Allen gone two years, is still so raw she hasn’t been able to pick up a paintbrush. She’s a fine art teacher we’re told by way of a former, now fully healthy student Gogo, Schiap’s real daughter. Nicknamed presumably for her flightiness, she’s always on the go, especially to the French Riviera’s yachting lifestyle. Schiap’s motherly love and protection exceeds her passionate career ambitions, one reason we like her so much. She seems to be the only one seriously preparing for the war that’s coming.

Charly: Lily leaves England when she receives an urgent telegram from her brother Charly saying he needs her. Lily adores “the handsomest man in Paris,” which gets him in trouble with women. The two were orphaned young, raised by an aunt in New York, so they depend on each other.

From the start, the prose is imbued with color, sometimes also referencing an artist’s work. Picture Charly picking Lily up at a famed Paris cafe in a “blue Isotta Roadster,” the shade of blue “Gauguin used to paint the Tahitian lagoons.”

Ania: Beautiful, graceful, and wealthy through a miserable marriage, fittingly dressed in Coco’s couture, is the woman Charly has fallen deeply in love with. Her personal life is a mess, so he needs a chaperone to be seen with her. Dangerous as she’s also having an affair with a high-ranking, historical German officer, and she’s Jewish. (Her parents live in Poland, the country Hitler invaded next.) Charly plans to take Ania to the ball of another historical figure, Elsie de Wolfe, so Lily needs a gown. She prefers Schiap’s colors as underneath her sadness is an artist who loves color.

Schiap: Takes Lily under her wings, expecting her to watch over Gogo and keep tabs on her nemesis Coco. One-by-one, she gifts Lily her designs to “armor” her, be her “good-luck charm,” fueling Coco’s bottomless jealousy as Ania starts wearing Schiap too, signaling how torn her loyalties are.

Coco: Lily connects Ania to Schiap but it’s Ania who opens the door for Lily to meet Coco, who’s flirting with having an affair with the same powerful German officer Ania is. Lily also meets his quiet driver, a minor character until he plays a vital role in the primary plot-line: whom to trust, whom to befriend, whom to love, how to survive. Coco is awfully alone despite her fame and fortune, enabling Lily to relate to both designers.

Baron Hans Gunther von Dincklage: Head of German propaganda, intimate with Hitler’s plans. Mixed up with Ania, eyed by Coco, he’s one of many historical characters who frequent the Paris Ritz, where Coco lives in “luxury and privacy.” Here is where Lily feels the “desperation of people who sense there is much, too much to lose.” People who understand they’ll need to take sides before the war reaches them.

It’s fascinating how Mackin unfolds Coco and Schiap. Coco grew up extremely poor in an orphanage, suggesting her designs were a nod “to the subdued colors of austere orphanage life.” Schiap’s rich Roman family gave her a lust for a vibrant life.

Schiap believed “fashion is art, not just craft.” Likewise, Jeanne Mackin’s canvas expresses more than the skills of her craft. Artistically, she chooses three colors for her palette and focus, enabling her prose to communicate the multi-hued emotions, loyalties, and atmosphere during a multi-faceted time in France’s history.

Lorraine