Mercy under the Big Top (Holocaust, 1942-1944; Darmstadt, Germany and Thiers, France): Tear-jerker alert! Pam Jenoff has outdone herself in her ninth historical novel of unimaginable feats during an unimaginable historical era.

Mercy under the Big Top (Holocaust, 1942-1944; Darmstadt, Germany and Thiers, France): Tear-jerker alert! Pam Jenoff has outdone herself in her ninth historical novel of unimaginable feats during an unimaginable historical era.

The gut-wrenching movie Denial about Holocaust deniers, released as anti-Semitism is rising, screams there’ll never be enough stories drawn from the Holocaust. Not just the inconceivable acts of horror, but the inconceivable acts of heroism, endurance, self-sacrifice. The Orphan’s Tale is all that, and more.

Two female narrators recount this death-defying story of circus aerialists when the “entire world hangs in the balance.” A survival story where love bloomed “in the most unlikely of places.”

Two pieces of Jewish history unforgettably converge: centuries of Jewish circus families and the heartbreaking account of “Unknown Children” dumped in a boxcar headed to a concentration camp – unknown even to Jenoff, a former State Department diplomat on Holocaust affairs. The novelist cannot forget nor wants us to, so she’s woven together unfamiliar truths and emotional fiction into a page-turner that may leave you in tears. As it left me.

A prologue opens the novel 50 years hence at an art exhibition on “200 Years of Circus Magic” held at the Grand Palais in Paris. French (and German) words are sprinkled throughout, invoking the two countries where the novel is set. You’re hooked because we’re not told whose voice we’re hearing. We do know this person planned for months to sneak out of a nursing home to get to France. By the end, you’ll figure out whose voice this is, bringing a little closure. Not much as this tale’s not meant to ever feel closed.

In the next 25 or so pages, you’re swiftly introduced to the plight of two women whose first person accounts narrate: Noa is 16 and Astrid 10 years older. At first, their only connection is they’ve both lost their families as a result of the war. Linked by sadness, for different reasons.

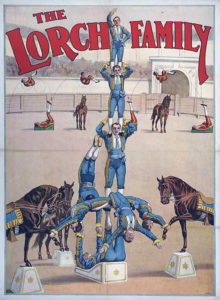

Noa’s parents threw their young, unworldly daughter out of her Dutch village home when she became pregnant by a Nazi soldier. Astrid, an aerialist with a “body like a statue, elegant lines seemingly carved from granite,” comes from a 100-year-old Jewish circus family – Circus Klemt – forced out of business in 1930 by the Nazi regime. Based, I think, on the internationally renowned Jewish Circus Lorch, which lasted 130 years. I’m not certain since it’s one of a surprising number of Jewish circus families Jenoff cites. In 1942, Astrid went looking for them in Darmstadt, Germany, but they’ve disappeared. Also in Darmstadt is the winter training grounds of Circus Neuhoff.

That’s where Noa and Astrid’s connection deepens as they both find refuge in this circus inspired, I believe, by Circus Althoff, also historically referenced in the novel. Adolph Althoff saved Jews during the Holocaust like Herr Neuhoff does. Both employed a Jewish performer who was a member of the Lorch family.

Poster for the Lorch Family’s act (c. 1915)

Document © The John & Mabel Ringling Museum of Art, Online Collections

via Circopedia.org

Both men also went to extraordinary lengths to hide Jews among the “chaos and intensity of the circus.” Neuhoff’s small stature (5’3”) belies his huge heart undeterred by a heart condition (like Althoff.) The novel is replete with dramatic contrasts like this, “characters in the wrong storybook.”

Noa speaks first. It’s 1944 and she’s made her way to Germany, eking out an existence cleaning bathrooms in the Bensheim rail station. She detects sounds coming from a parked boxcar, rashly rushes out into the freezing snow risking being spotted by the German police, an act that alters her destiny. Actually, her fate was sealed when she gave birth to her Jewish son at a German hospital expecting he’d be adopted by a German family since she’s blonde. Did she know the Lebensborn program was “one of the most secret and terrifying projects” aimed at creating a “racially pure” society? Nothing suggests she did.

Grief, sorrow, guilt propel Noa to the boxcar featured on the cover, loaded with crying infants, crammed and packed so densely she can’t find a space to step into. Somehow she stretches far enough to grasp one baby boy; continually regrets she couldn’t save more. He’s circumcised, a Jewish baby, like the one she abandoned. This time she’ll fiercely protect him no matter the danger. Much of the novel reads at this breakneck pace.

Imagine Noa at this moment. Her makeshift sleeping arrangement in the railway’s closet is now impossible. Then imagine what it felt like when she meets ringmaster Neuhoff, offering her and her baby, Theo, refuge on the condition she perform with one of only a few aerial artists in the world who can execute the triple somersault – Astrid, whom Neuhoff is also protecting. Noa must learn the Flying Trapeze: flying through the air with a flimsy net nearly touching the floor.

Astrid’s lost more than her circus parents. Her prowess is what she clings to. “The air was all I had known,” she says. The two begin working together, more like battling as training to “take flight” takes years of mastery. Yet they only have a few weeks before they travel to Thiers, France!

For Astrid to catch Noa she must trust her, which means Noa must come clean about Theo. How to trust when “everyone needs to hide the truth and reinvent himself in order to survive”? A moral dilemma that plays out over and over, as both women harbor secrets.

The circus is a “great equalizer,” so others have hidden pasts too. Peter, “a sad clown fitting for these dreary times” is key because of his deepening involvement with Astrid. Astrid and Noa’s complicated partnership grows too. These relationships drive the nail-biting suspense.

This is a full-fledged circus – more clowns, acrobats, Fortune Teller, Gypsy, elephants and tigers and their trainers, other “defying gravity” acts like the High Wire, and a cast of workers that make this “huge enterprise” function and dazzle even though behind the scenes it’s plain old hard work, not at all exotic.

What is alluring is Jenoff’s lyrical prose evoking the world of aerialists. “Circus artists are every bit as intent as a ballet dancer or a concert pianist. Every tiny flaw is a gaping wound.” Here technical proficiency is a life-or-death proposition – cradle swings, hock-and-ankle catches, swing passes. And, the show demands presence, charisma. “Think graceful,” Astrid commands Noa, “dance, use your muscles, take charge.” The “audience is all around us like sculpture,” so Noa must also learn to think “three-dimensional.” The “lights and a thousand eyes upon you change everything,” so Noa must also learn to flash “personality, flair, the ability to make the audience hold its breath.” What a relief Noa displays “agility and strength” owing to earlier gymnastics training. Still, you’re gripped when she climbs the ladder to heights most of us dare not go and struggles to learn how to let go.

Against the backdrop of the Holocaust, its unimaginable the circus even existed. Like this unimaginable tale of finding family when millions were lost.

Lorraine