The artist obscured by her famous sister (Concord and Boston, Massachusetts, London, Paris and villages, Rome, 1868 – 1879): Calling all feminists, aspiring artists, historical fiction buffs, and readers who relish genteel prose and old-fashioned letters with big, thought-provoking, timely themes.

The artist obscured by her famous sister (Concord and Boston, Massachusetts, London, Paris and villages, Rome, 1868 – 1879): Calling all feminists, aspiring artists, historical fiction buffs, and readers who relish genteel prose and old-fashioned letters with big, thought-provoking, timely themes.

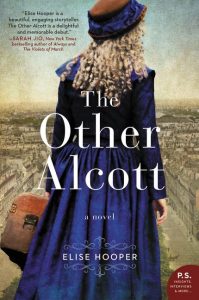

Now couldn’t be more fitting to read The Other Alcott published last year, as 2018 is the 150th anniversary of the never-out-of-print Little Women. This is a March sister story we didn’t know, about May Alcott, one of the four sisters (Jo, Meg, Lizzie, Amy) depicted in Louisa May Alcott’s beloved children’s classic, drawn from her family. Amy March, inspired by May, became an acclaimed painter during an important historical era. The Other Alcott brings her to life in this packed-with-history 400+ page novel.

What we know of May was how she was portrayed in her sister’s literary hands when May was twelve. While the book was a huge, much-needed financial boost for the impoverished Alcott family, ironically, Louisa considered it and sequels Good Wives, Little Men, and Jo’s Boys “hokum,” balking at being pigeon-holed into writing them by her publisher. (She also wrote under a pseudonym, A. M. Barnard, hiding her identity and gender to be free to write like the maverick family she was born into).

May is twenty-eight when her story begins.

The epistolary format is used quite effectively from time to time. The novel opens with a sorrowful letter May wrote to Louisa but never sent, revealing the two had been estranged for quite a while and that theirs was always a difficult relationship:

“I long to turn back the clock and mend the rift between us, though now that I think on it, if I could go back in time when would I go back to? When was our relationship ever simple?”

May “favored happy endings,” so from the beginning we’re lured into wondering if she and Louisa ever made up? What caused the serious rift?

Elise Hooper is a history and literature teacher who grew up near the Alcott’s much-publicized home in Concord, Massachusetts: Orchard House. (They moved over twenty times before settling there.) It’s fair to say Hooper has been intrigued by this unorthodox family since childhood.

Father Bronson was a philosopher, member of the Transcendentalist movement who communed with nature and shunned traditional values, leaving his family so poor he needed his neighbor and philosopher friend Ralph Waldo Emerson to support the family until Louisa takes over. (Nathaniel Hawthorne, another neighbor and transcendentalist.)

Curiosity about May led the author to dig extensively into her history to find out what she could, and then imagined the rest.

Expect to see painterly prose expressing May’s love of painting (“chokeberry bushes, luminous in a hue straight from a tube of vermilion paint”), and mostly real historical figures. Some famous, but it’s the cast of also unknown female artists May encounters and befriends during the course of her artistic development that add another layer to the novel’s richness.

Orchard House is now a museum, evoking the Alcotts’ past like Hooper’s novel.

As a fan of Author’s Notes that distinguish fact from fiction Hooper’s are exemplary: a wonderfully informative nine-page Afterword, followed by another lengthy Conversation with the Author, describing “what became of” the historical female artists. They’re introduced to us in five chronological parts that track May’s travels to pursue her art: to Boston, London, Rome, Paris and two charming French villages.

The focus of the novel, of course, is what became of May?

May was shaped by an outgoing, winsome personality, in extreme contrast to Louisa’s solitary, brooding soul; her non-conformist family; art masters she mentored under; artist friendships; infatuations (one with her art teacher) and a genuine love; and American and European art movements of the day.

Unlike Louisa, she wanted to have a happy marriage and an art career. Family obligations dictated by Louisa often interrupted May’s work, contributing to her resentment of her prickly sister (though she was dedicated to her ailing, toiling mother, “Marmee,” an abolitionist, a suffragette like Louisa.) She longed to make it on her own, influenced by poverty and burdened by indebtedness to Louisa, so she too-willingly adhered to the limiting constraints of the male-dominated, conservative art worlds to gain acceptance, sell her work. Conflicted by admiration for Louisa’s fierce independence (though she did not want to be a spinster), and a range of disquieting emotions as judgmental Louisa believed May’s “desires for comfort, happiness, and stability to be shortcomings, moral failures, signs of selfishness.”

Depicting Amy March as self-indulgent is seen as the source of original tensions with Louisa. It was terribly humiliating (and unfair) to be viewed this way to a wide public adoring her sister’s book. May’s illustrations accompanied it, harshly criticized too. This double “pain of rejection” stuck with May affecting her self-confidence, her artistic exploration.

Hooper focuses her light on an age when women were fighting for equality in many arenas of society. Few art classes were even open to women, and Louisa paid for most of May’s.

In Boston, May was frustrated and stymied by the rigor of exercises in anatomical preciseness as the market was portraiture and photographic-like landscapes while her softer sensibilities were watercolors, something more flowing. She studied under a medical doctor-artist who grilled his students in anatomy; she struggled with sketching live models. She lived with Louisa at the defunct Bellevue Hotel (now condos), where Louisa feverishly immersed herself in non-stop writing to the detriment of her already compromised health. This swanky hotel in Beacon Hill signified Louisa’s increased earning power beyond the $1.50 she was paid for Little Women!

In London and Paris, May discovers “art lives in the galleries and museums,” but “in Rome, it’s everywhere.” A city filled with constant intersections between art and life,” enhancing connectedness to history and aestheticism.

May gets advice from the likes of Elizabeth Jane Gardner, Helen Knowlton, Anne Whitney, and fictional Alice Bartol, fashioned from the real Alice Bartlett and Lizzie Bartol. “Stake a claim on your ambitions, counsels Jane. “If you wait around for other people to define you, you’ll be saddled with their expectations – and that’s dangerous territory for a woman.”

It took years for May to figure that out. Her breakthrough comes when Mary Cassatt enters the picture. Still an uphill battle, soul-searching the artist she was and the one she wanted to be. Mary was in the midst of her own existential crisis, at the cusp of abandoning the prestigious, obsessively competitive Paris Salons, eventually joining forces with what evolved into the Impressionist movement. Degas and Monet make a brief appearance.

The rise of Impressionism is symbolic of what May was up against. It takes most of the novel for her to summon the courage to break out of the mold, to be bold. You can see how far she came in her best known work, a small, striking painting, La Négresse, considered her masterwork.

“We’re all students, Helen Knowlton says. “This is one of the beauties of being an artist: there’s always more to learn.” May’s artistic journey offers lessons on how “to find something special inside ourselves.”

Was she ever able to find that special place inside herself to reconcile with Louisa? A poignant path worth taking.

Lorraine