Fantastical Nature as Fantastic Therapy (Orkney Islands, Scotland and London, recently): Judge this life-affirming book by its eye-catching cover. Where in the world is the smoothed-over-centuries rocky coast? Hint: somewhere “between the North Sea and the Atlantic.” Who is the tall, slender, modelesque young woman meditating? Hint: she’s an “edge-lander,” someone who grew up near the edge of the world.

Fantastical Nature as Fantastic Therapy (Orkney Islands, Scotland and London, recently): Judge this life-affirming book by its eye-catching cover. Where in the world is the smoothed-over-centuries rocky coast? Hint: somewhere “between the North Sea and the Atlantic.” Who is the tall, slender, modelesque young woman meditating? Hint: she’s an “edge-lander,” someone who grew up near the edge of the world.

Amy Liptrot not only lived on that edge geographically – the Orkney Islands, north of Scotland – but also behaviorally, “always seeking sensation and raging against those who warned me away from the edge.” That edge shaped and defined the author and her award-winning memoir, remarkably soothing for a “wild girl” recovering from alcohol addiction on wild islands. Yet not so surprising for a girl who spent her childhood “living among the elements.” A childhood of “dramatic scenes,” earthy and personal.

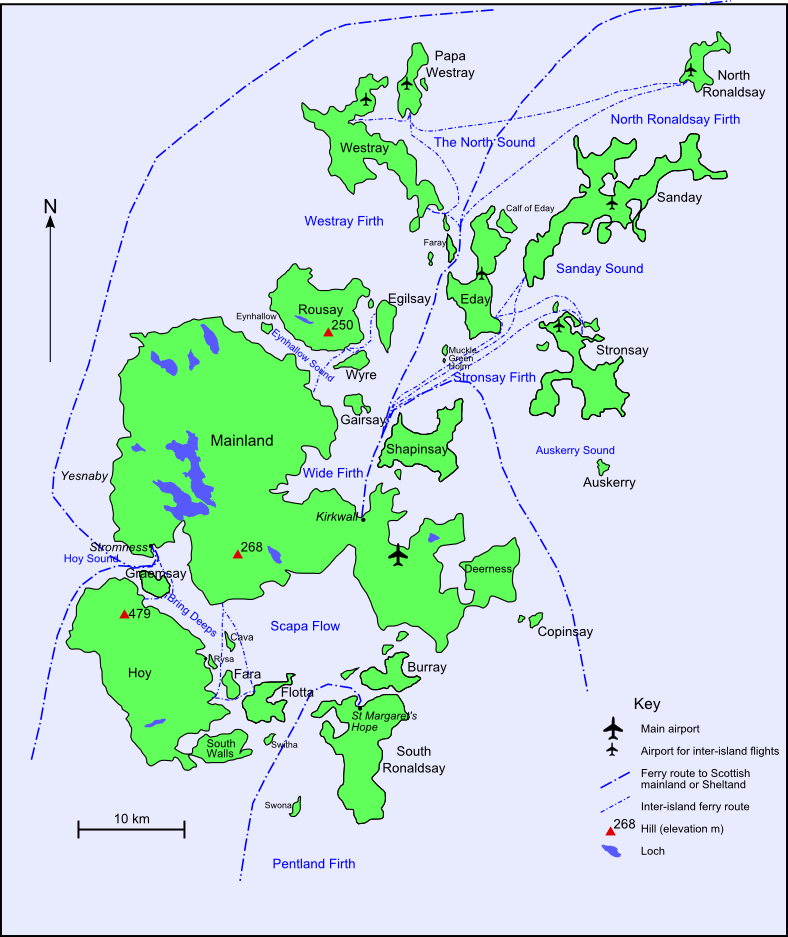

Map of Orkney by Mikenorton [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The heart of the memoir takes place on the Orkneys two years after the author made it through an intensive rehab program in London, where she hit rock bottom. (Her brother, who attended the same university as she did, tried to help until she needed aggressive intervention.) Today, at thirty-five, she’s five years sober.

Some 20,000 people are estimated to be living on the seventy islands that comprise the Orkney archipelago. Many are sparsely populated or completely uninhabited. Most of the memoir’s Orkney sections are set on the so-called Mainland where the author’s family farm is located, and on one of the northernmost islands, Papay, population seventy. Liptrot chose to spend five winter months on this remote island feeling less alone than she did in London. If you read to experience new worlds, The Outrun will definitely take you to one.

Much of the exotic language – references to the far northern reaches of an ancient landscape, culture, history, and folklore – is otherworldly. A world in which you don’t just see shooting stars in the night skies, you see galaxies, planets (four, unbelievably, on one night), moonbows (rainbows caused by the moon’s light), and the Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis) or what this poetess of Nature calls Merry Dancers.

Not everything is merry, of course. Liptrot didn’t become sober until thirty (she started drinking at fifteen), when she returned home trading “disco lights for celestial lights.” A steady, uphill process that replaced her dependence on alcohol to feel “more alive” to getting high on her unique “natural surroundings,” birdlife, and sea life. She found she could get “high on fresh air and freedom on the hill” and “that being sober could be kind of a trip and I was just riding it out like a soldier.” A magical, mystery ride.

Our first indication that The Outrun is going to be out-of-the-ordinary is that it opens with a helpful glossary of Orcadian words. Some are farming terms like byre for barn and kye for cattle since Liptrot grew up on a croft farm. More than an unfamiliar word, crofting is a landowning culture that dates back to the late nineteenth century when a farmer rented a small piece of land along with a croft house. (Liptrot’s childhood farmhouse is that old.) These houses seem to have personalities, with names. In fact, croft houses tended to outlive their temporary landowners, so people are more likely to be identified by the names of their croft homes rather than their own.

“I grew up in the sky, with an immense sense of space,” Liptrot tells us, but she felt “limited by the confines of the island and the farm.” That edge-of-the-world farm included uncultivated land called the outrun, described as land “where domestic and wild animals co-exist and humans don’t often visit.” Liptrot spent the first eighteen years of her life walking on the windswept coastal cliffs of this outrun, neighboring one of the most intact New Stone Age archaeological settlements (Skara Brae) anywhere, a World Heritage Site.

For all its wonder, the Orkney’s are “desolate-seeming.” Liptrot herself was lonely and sad for a very long time, trying to fill a “void” she couldn’t seem to fill, “bottomless pain.” So how could we not rejoice in her eloquent revelations of “filling the void with new knowledge and beauty” upon finding herself as she rediscovers her homeland?

Still a thrill seeker, she swims in the frigid, pounding North Seas with a polar bear club, an unimaginable “cold-water high.” Thanks to technology and the author’s intensely curious mind and “perpetual hope,” she carved out fascinating activities and interests. Became a passionate bird watcher, stargazer, rare cloud studier, astronomy buff, weather-watcher, and tracker of marine traffic, flight radar, tidal charts, sunrise calendars. “In the islands in the age of digital media, we often find that, although it seems contradictory, technology brings us closer to the wild.”

If you’re a birder, conservationist, environmentalist, tuned into the endangerment of species, this memoir is for you. There’s hundreds of bird species on these islands, along with an active, long-standing RSPB – the Royal Society for the Preservation of Birds. Like Artic terns, fulmars, puffins, shags, black-backed gulls, gannets, whaups (also called curlews), tysties (or black guillemots), kittiwakes, razorbills, turnstones, golden plovers, snipe. There’s even an Orkney phrase for hunting seabirds: swappin’ for auks. For a while, the author raced to count endangered corncrake birds for the group on Papay. Liptrot compares herself to the corncrakes “clinging to existence,” saying she’s “clinging to a normal life.”

Nature and wildlife are gifts wherever we live on earth. On the Orkneys these gifts are extraordinary and abundant. But it’s Liptrot’s courage, perseverance, amazement, and phenomenal zest for immersing herself in these gifts that enabled her fulfillment and healing, one day at a time. Inspiration we can all cling to.

Lorraine