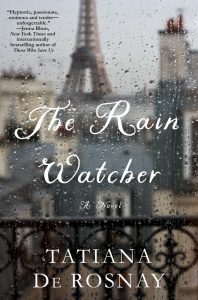

What happens when a family crisis collides with an environmental crisis? (A week in January in Paris, present-day): Despite the rain in the title and the raindrops on the cover, we don’t expect The Rain Watcher to be an urgent call on climate change. What we expect is some sort of a family calamity, not an environmental one happening simultaneously. The combined effect is to humanize the emotional havoc an environmental disaster places on a family already in crisis. Two fictional genres – dysfunctional family fiction and climate fiction inspired by historical facts – double punch this family.

What happens when a family crisis collides with an environmental crisis? (A week in January in Paris, present-day): Despite the rain in the title and the raindrops on the cover, we don’t expect The Rain Watcher to be an urgent call on climate change. What we expect is some sort of a family calamity, not an environmental one happening simultaneously. The combined effect is to humanize the emotional havoc an environmental disaster places on a family already in crisis. Two fictional genres – dysfunctional family fiction and climate fiction inspired by historical facts – double punch this family.

France’s bestselling author Tatiana de Rosnay (Sarah’s Key , A Secret Kept, The House I Loved, more) uses a literary style that seems designed to make the reader feel the growing anxiety of the family’s worsening situation as the waters of the river Seine rise and overflow. The prose has a very distinctive quality: long sentences that turn into unusually long paragraphs – one, two, three pages long. The author wants us to feel the panic.

We’re so used to short paragraphs and clipped chapters this literary approach places demands on us; soon it sweeps us along as both disasters unfold, intersect, and devolve. There is, though, brevity in prologues that preface each of the novel’s six lengthy parts. However, it’ll take you most of the novel to nail down the narrator of these prefaces, a young boy, and how he figures into the multi-layered plot.

The last time the Malegarde family of four were all together was thirty years ago. They’re meeting in Paris to celebrate the 70th birthday of Paul, the patriarch, and the anniversary of Paul and Lauren, who planned this reunion for two years to make it happen. They have two children, Linden, in his 30s, and his sister Tilia, 40; her daughter, Mistral, 18, also arrives.

The first thing to know about the family is the names Linden, Tilia, and Mistral are all inspired by Nature. Lime trees are also called Linden, also Tilia in Latin; Mistral stands for a “powerful northwesterly wind.” Their names are connected to a piece of inherited property, “a little paradise on earth.”

Located in the Drone Valley some four hours south of Paris among fields of lavender and farmlands, a beautiful landscape where Paul and Lauren live; Linden and Tilia grew up here. Surrounded by lime trees, one at least three-hundred years old, and an arboretum, both mean everything to Paul. Famously known as Mr. Treeman, he’s an arborist who saves ancient and magnificent trees around the world. “A mystery to his only son,” a mystery to everyone actually, because he prefers trees over people, fanatically. A “silent” man, Linden “has been missing his father’s voice all his life.” He wants to communicate with him, doesn’t know how. (A running theme in the family’s dynamics.)

Trees also enter the picture with the unknown boy narrator whose voice is heard from a treehouse. Each time he appears we learn a little more of his traumatic story, but we don’t understand its relevance to the plot, germane in the ending.

The novel is as much about unlocking the importance of Nature as it is about unlocking the nature of people.

Each relationship in the family is examined, not separately but woven into the flowing paragraphs. Linden is the star. It’s his voice and his relationship with Paul that’s center stage. Linden lives in San Francisco, a photographer as famous as his father. In fact, it was his shot of his father, Treeman Crying in Versailles, that brought Linden overnight fame.

Linden has charisma. “Even people who had barely met him were bowled over by his personality, his kindheartedness, his talent, his sense of humor.” Love and kindness take over when Linden finds he’s the only family member who can, and will, assume the role of managing his distressed family. This does not come easy for him, expressed through his long, searching prose.

Linden left his family when he was a teenager; moved in with his aunt Candice, his mother’s sister, in Paris. He told her he was gay, she loved him “just the same.” Yet he didn’t tell his “nonchalant, exquisite mother” until seven years later expecting she’d react poorly, which she did. He’s never told Paul but suspects he knows about his lover, Sacha. “Never would he have imagined it would be so tough coming back” to Paris as Linden’s regrets and secrets about Candice and a young man resurface and deepen as the flooding paralyzes the city.

All the family members have secrets and regrets. Mother and father, individually and as a couple, are not revealed until the last fifty or so pages.

Tilia too. Tormented by a tragedy in her past, she’s a “failed artist.” She lives in London with her second husband, Colin, a mean alcoholic. Her “life is a disaster,” saved by “magnificent and fearless Mistral,” who “mothers her own mother brilliantly, and has been doing so, it seems her whole life.” Mistral and Linden are close, drawn to each other’s sensitive souls. Mistral is “bubbling” with excitement around uncle Linden so her prose bubbles along. She’s a big support to Linden in the emergency role he struggles with, yet done with great strength under great duress.

“The river has turned into a gluttonous muddy monster … “The river seethes like a hostile reptile beneath leaden skies and the uninterrupted downpour.” A statue, Zouave, marks how high the river Seine rises. The more intense the family’s situation becomes the higher the waters rise.

Statue of the Zouave, Paris

By Yann Caradec [CC BY-SA 2.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

Another tragedy is Paris had warnings: the 1910 Great Flood of Paris, revisited over and over again as people keep wondering if 2017 will be worse than 1910 when the waters rose 28 feet. (2016 flooding in Paris also noted.)

As the city becomes deluged, few can escape. Certainly not this family. Fear, exhaustion, and time feel like an eternity wearing down these characters until they weaken and finally share their innermost secrets, enlightening each other, enlightening us.

How sad that it takes a catastrophe to get the family to open up. Sad because they love each other, in their own imperfect ways, but there’s so much underlying baggage and tension among them they’ve been unable to. The Rain Watcher is a tale of many kinds of love, especially unconditional love and “love unexpressed.”

Human lessons are also viewed through an environmental lens. An historian discusses 1910 vs. 1917 flooding as the world watches the devastation in Paris on TV. The human connection is also told in a message about trees from Linden’s father he hears on a video.

The historian discusses the technological facts that made it easier for people to cope in 1910, but what sticks out is how “people were kinder to one another” compared to today as looters ransack an already ravaged city. And, Paul (who is quite talkative when it comes to trees) says: “trees care for one another … “everything about a tree is slow, how it thrives, how it develops … a tree is the exact opposite of the crazy, fast times we are living in.”

Given the dire warnings on the human toll of global climate change recently reported on, The Rain Watcher cries out on both the personal and scientific front. Tatiana de Rosnay hopes we’re listening.

Lorraine

Excellent review!

The novel is a masterpiece of story telling, great compassion for the dysfunctional family and appreciation of the trauma of childhood experiences. It also speaks to the courage of a son to want his dying father to know him and accept him as a gay man., which releases the repressed father’s long held secret that gives insight into his own behaviors. Too, the courage of a more traditional mother to embrace her gay son, and express love and admiration for him as she reveals her own secrets. It is a very powerful portrayal of lives examined. And we the readers are the lucky recipients of those insights. Thank you Tatiana.

Hi Lori,

Appreciate your insight. Thanks for your comments. Lorraine