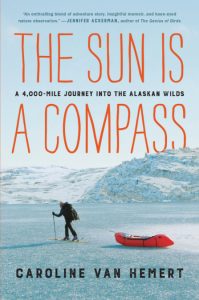

Extreme adventure that reads like unimaginable fiction (Washington, Inside Passage and Arctic Alaska, Canadian Territories; six months 2012): If a picture is worth a thousand words, take a look at the video Caroline Van Hemert and her husband Pat Farrell shot during their six-month, mind-boggling expedition covering 4,000 miles of stunning and death-defying landscapes in the northernmost reaches of North America – the subject of this thrilling and beautifully written memoir:

If you cannot imagine adventuring through the Inside Passage of southern Alaska to the Arctic Circle, and doing so entirely with your own “muscles” (travel by an “expedition-style rowboat” Pat built, an inflatable packraft, skis, hiking), in some of the most “bear-dense landscapes on earth” (no gun, just bear spray), amidst “hurricane-force winds,” avalanche dangers, glaciers, snow-covered boulders, mud like quicksand, in temperatures that plunged as low as negative 50 degrees Fahrenheit, across remote backcountry few (if any) humans live, then reading The Sun is a Compass is like watching a National Geographic Special with eye-popping wows.

You’ll also find yourself thinking, like the author writes in her planning notes, “Is this crazy?” The answer is an unequivocal yes; this wild journey undertaken in 2012 was CRAZY! Maybe not quite that absolute for a couple cognizant that “wilderness has become the silent partner in our marriage.”

The author has a way with words that brings awesome wilderness to our doorsteps. Coupled with amazing courage, endurance, persistence, and risk-taking, this is an amazing story of recognizing “certain things in life don’t offer second chances.”

How two extreme adventurers achieved what they’d set out to do (with four months of planning that wasn’t enough), prepared for, experienced, and survived is the stuff of legends. In fact, I googled to see if they’d received any kind of explorer award, surprised not to find any. The memoir should attract wide attention to compensate for that, though it seems highly unlikely these adventurers care much about that. They are the real deal.

Honestly, I don’t know which aspect of their journey stands out the most. I’ll mention some, let you decide.

The author, who submitted her doctoral thesis the night before they set off, is a wildlife biologist specializing in ornithology. Surely her knowledge enriched what the couple saw and felt. Being able to identify a long list of birds acclimated to frigid climates and birds in the midst of the miracle of migration – birds with “remarkable feats of memory and problem-solving” – added immeasurably. So many birds, which you’ll find listed in a detailed index. Warblers, godwits, chickadees, kittiwakes, trogons, gulls, goshawks, guillemots, gyrfalcons, plovers, tussocks, and many more. Enough to satisfy a birder’s life list! But the purpose of spotting them and telling us a little about them is meant to highlight moments “filled with “wonder.” The bird image that sticks with me is the time they came upon a single “trumpeter swan taking a bath” in a glacial lake at five thousand foot elevation.

Seeing these birds in their natural habitats brought the author closer to the field work she’s passionate about, not the academic research she’s dispassionate about – one reason among several this journey was so important to her.

Van Hemert was thirty-three when she and her husband made this expedition, a fork-in-the-road time in their personal and professional lives, expecting it would clarify decision-making especially for the author who “needed a crash course outdoors to remind myself that life is not merely a tally of days, that what really matters cannot be quantified.”

Pat’s path, on the other hand, seemed somewhat determined. A builder of things, he ended up founding an Alaskan company that custom-designs homes for unforgiving climates. The author, who tends to worry compared to her unusually optimistic husband, currently works at the US Geological Survey in Anchorage, Alaska after much soul-searching.

Van Hemert tells her story when she was at a vulnerable stage in life, unsure of her career direction and motherhood (her sister gave birth shortly after the expedition began), concerned, rightfully so, as to how a child would fit into/constrain extreme adventuring. But family is precious to her; she poignantly stresses about her active father’s recent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The trip may be off-the-charts unknowable to most of us, but the personal conflicts and worries are awfully familiar.

While Pat’s arrival in Alaska came via upstate New York (he content to “live in the woods”), the author was raised in Alaska by highly supportive parents who loved and encouraged the outdoors. Van Hemert is devoted to them too, touched they’d think nothing of driving 1,000 miles north to deliver and exchange supplies. Care packages always included much-needed food that was never enough and, except for calorie-laden treats they devoured on the spot, quite dissatisfying (dehydrated and dry food) to reduce the heavy loads strapped on their backs. Imagine how many calories expended in a day! Many times nourishment ran seriously low, one time the author so starved she could barely move. A couple of times the two were saved by “Arctic hospitality,” generous strangers they met in sparsely populated, remote villages or tiny outposts.

While the birds are lovely to read about, it’s the bears that give most pause. They encountered 47 bears; only one was so aggressive they’re lucky to be alive.

Perhaps more impressive was witnessing herds of porcupine caribou crossing waters, “one of the last great migrations of large mammals on earth.”

Also unforgettable was the first 1,200 miles of their trip paddling in over-sized, sleek yet 100-pound, 18-foot rowboats. They were sailors, kayakers, canoers used to staying close to each other; these oars were too long to permit that. Sometimes they rowed without seeing the other – daunting aloneness when dealt with unpredictable, fiercely raging Spring weather when they left from Bellingham, Washington. We’re talking six foot waves, “rowing in the dark through the biggest tide of the decade.”

Those images bring to mind another indelible scene: paddling amongst 40-ton humpback whales breeching.

And yet, when a goat falls off a mountain and recovers gracefully, reminding the author to relish not fear the beauty engulfing them, that graceful goat serves as a symbol of wondrous, fleeting moments. That some of “the most precious things in life are those that don’t last forever.”

Above all those vivid scenes, the climate change message we mustn’t forget. Given the threat to endangered species the Trump Administration endorses, so utterly contrary to grave scientific global warming predictions, observing musk oxen return to the Arctic having vanished after 90,000 years on earth is an encouraging sign that maybe it’s not too late, yet.

The “entire Arctic Marine ecosystem is in peril,” the author writes, evidenced by paddling alongside gigantic ice floes broken off from what used to be “land of persistent ice,” and discovering the relics of creatures lost to the climate’s warming. “Bleached white bones are everywhere as if an entire museum collection had been emptied onto the beach.” The prose ought to alarm. Species are endangered because our environment is endangered.

You don’t have to go to such extremes traveling to the “land of extremes” to believe this. (Colorful, glossy photographs tucked inside show how extreme. The very last picture is a spoiler, so suggest you finish then peruse.) Still, we should applaud two brave people who went to extremes, now warning those who’ve gone to extremes to deny climate change is upon us.

Lorraine