Rising up to racial injustices (Los Angeles, 1980s to today): Can one book stun enough, reveal enough, connect-the-dots-enough to move hearts and minds? If you believe, as activist, artist, and author Patrisse Khan-Cullors does, that “all lives will matter when black lives actually matter,” perhaps the question isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds.

Rising up to racial injustices (Los Angeles, 1980s to today): Can one book stun enough, reveal enough, connect-the-dots-enough to move hearts and minds? If you believe, as activist, artist, and author Patrisse Khan-Cullors does, that “all lives will matter when black lives actually matter,” perhaps the question isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds.

You can hear Cullors say those words in an interview with actor Morgan Freeman – see video below. In it, she shares some of the catalysts that led to her founding (along with Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi) the Black Lives Matter movement five years ago. She speaks of: the terrorism her gentle brother Monte endured in the LA County prison system, largest in the world, where a “pervasive culture of hyper-violence” was “astonishing,” concluded an FBI investigation; the take-my-breath away acquittal of a white man, George Zimmerman, who gunned down 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida claiming self-defense; the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, a white policeman absolved of shooting another black boy. Black Lives Matter began as a local reaction to a lack of accountability, racial profiling, and police violence; today it’s a national and international social justice movement “committed to struggling together and to imagining and creating a world free of anti-Blackness, where every black person has the social, economic, and political power to thrive.”

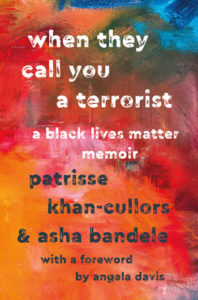

The clip is a snapshot of the disturbing and rousing stories, revelations, and emotions voiced in When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter memoir. Page after page of poetic and unflinching prose depicting “a stunning betrayal of human dignity.”

Backed up by eye-opening data and calls to action by a string of past and present writers, poets, advocates, scholars, and journalists, the memoir illuminates the gravity of consequences on children, families, and communities when they are systemically oppressed by “racism, sexism, classism, and heteronormativity,” enormously complicated by circumstances that doom them.

Shutting down the GM plant Cullors’ father, Alton, worked at in their Black and Latino “cash poor” Van Nuys neighborhood in Los Angeles is that kind of mortal blow. In these impoverished communities, so many are unable to lift themselves up and out without community supports and healthy outlets. Instead, substance abuse, gangs, physical and mental illness fosters and festers, which the “prison industrial complex” feeds on, explains Cullors, grinding down in the harshest of ways the message that your lives do not matter.

We think we know about these things, how far we’ve come and have far we’ve got to go. This slender memoir packs an impressive amount into showing us how much we really don’t know and how even more daunting the work we must do really is.

One reason it moves us so is the book feels like two books in one. Black lives do not matter parts and black lives do matter parts, blended together.

“What is the impact of not being valued?” Cullors asks, answering with words of profound sorrow, grief, and loss: “Wounds that went past the sinew and bones, laid claim to the marrow.” Then, “something deeper than sadness, an aching and hopelessness that finds home at a cellular level.”

It’s one thing to read statistics that 80% of those imprisoned in LA county jails suffer from drug addiction and 20% mental illness; it’s quite another to absorb what happened to Cullors biological father, Gabriel, whom she first met when she was twelve years old. In and out of her life for he was in and out of prison, in and out of 12-step programs that she attended too, witnessing his pain, buoying him. Provocatively she questions the fairness of instilling a belief that overcoming addiction is all within the power of the individual after seeing her father defeated by outside forces that were not held accountable for rendering worthless the power he mustered.

The tragedy of Gabriel’s vanishing is magnified as the newfound, big, noisy, Louisiana-roots family Cullors feels wonderfully right at home with is held together by this generous man – and suddenly they’re not. Imprisoned for succumbing to an addiction that sentences him to a life of depression, believing his life does not matter. “You can wake up one morning and find anyone, maybe everyone, gone.” A young heart becomes a “shattered heart.”

Yet, in the black lives matter parts that heart has the strength to be there, with so much love, for her brother who is repeatedly brutalized in prison when the place he desperately needs is a psychiatric hospital. It’s not clear whether his life sentence of schizoaffective disorder came first throwing him into jail, or the violence perpetrated on him in prison triggered the psychopathy. What is absolutely clear is that once he’s diagnosed, the worst place to be is locked up without any medicine, counseling, and humaneness.

Cullors’ tenderheartedness for her mother Cherice who works from 6am to 10pm to eek out a living for her family is another black lives do matter part. It’s remarkable how much love, hope, and spirit Cullors possesses in spite of it all.

I finished reading this stunning memoir on the Friday before we honor what Martin Luther King, Jr. fought for, stood for. That morning cable news anchors and commentators kept using a vulgar word in quoting the vulgarity and racial venom spouted by America’s 45th President about the black and brown peoples from Haiti, El Salvador, and 55 African nations. The release of this memoir isn’t just perfectly timed to remembering a civil rights icon; it’s timed to the “civil rights crisis of our time.”

This is not a political blog. But, as MSNBC anchor Stephanie Rule said on that unforgettable Friday, “this isn’t about politics, it’s about decency.” And about morality, equality, the character and soul of a nation. For contrary to the title of Georgetown University professor Peter Edelman’s Not a Crime to be Poor, in Cullors’ America it is a crime to be poor, and we learn big business.

The title of the memoir, co-authored with the former editor of Essence magazine, “the first mainstream publication to tell our story,” is an audacious reversal of the truths told: black people are the ones being terrorized.

The prose moves us, in many ways. In the enormous pride expressed for a long-lost grandmother:

“with a fourth-grade education who survived Jim Crow hatred and vicious rapes and unconscionable poverty and brutal domestic violence so she could sit on the other side of it all and still know most of us who had so much more than she ever did, that at the end of the day, from love we come. To love we must return.”

She moves us in her compassion for a toiling mother who keeps her emotions in check to survive but when her son, Monte, is wheeled into a courtroom tied down to a gurney and raging, his mental illness on full public display, she cannot stop sobbing in public.

There’s also prose that makes references to pop culture, urban slang, and justice organizations I was unfamiliar with. The Urban Dictionary came in handy! All with an eye towards opening our eyes up to diversity, tolerance, kindness, affirmation, healing.

Cullors is a courageous, peaceful, spiritual fighter. A 21st Century Civil Rights Leader who eloquently calls out fifty years after we lost Martin Luther King, Jr.

I wanted to start 2018 with an especially meaningful book. Here it is!

Lorraine