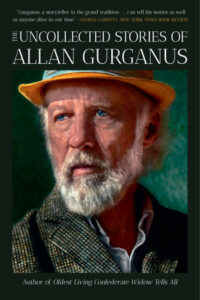

Humanity in storytelling (North Carolina, Iowa, Florida; 1970s to present day): “Literature represents my greatest hope for our species at its very best,” Allan Gurganus said when asked about his ideal reading experience. Based on his new collection of stories on the stuff of life and what makes us humans, there’s reason to feel hopeful about the future.

Gurganus is a keen and empathetic observer of people. Hailing from the South, Rocky Mount, North Carolina, many of his stories are set in his invented town of Falls, and yet he speaks to and for all of America.

You may know the author from his award-winning debut novel that brought him instant acclaim, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells Us, in 1989. His last work, Local Souls, was published in 2013, so these uncollected stories were anxiously awaited by the literary community. Also for good reason.

While the voice of some of the narrators in the nine stories conveys an old-timey style of storytelling, there’s nothing old-fashioned about the contemporary issues Gurganus tackles exquisitely – subtly, cynically, wittily, compassionately, open-mindedly, poignantly.

While this is the first time these stories have appeared in one collection, most have appeared in another publication at some earlier time, as noted in the Acknowledgements.

The opening story, for instance, “The Wish for a Good Young Country Doctor,” first appeared in the New Yorker magazine in its May 4, 2020 issue. As you’ll see in all of the stories, the plot – in this case about collecting Americana – goes far deeper than that. It also sets a semi-autobiographical tone. Although it’s not set in North Carolina as others are, it takes place in eastern Iowa within striking distance of the University of Iowa where Gurganus taught creative writing at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. One of his students is one of my favorite writers and most everyone else’s, Ann Patchett, who wrote that Gurganus “was and is my most important teacher. He writes with a deep and joyful expansiveness that is completely his own. Every story comes with a novel’s worth of heft and insight.” Not to be overlooked is that both writers have a distinctly authentic way with words and remarkable compassion.

The narrator in the lead story is a graduate student scouting for art that’s “ethnographic” for a class assignment. On page one, we’re told he’s written his master’s thesis on Hand-Wrought Iowa-Illinois Farm Toys, 1880-1920, part of his “American Studies” program. What could be more American than folk art? When he stumbles into Theodosia’s Antiques, he’s met by an ornery, eccentric (“weighing under ninety pounds” wearing “a county’s worth of brooch timepieces”), and wise proprietor who has plenty to sell but isn’t welcoming. She’s had her share of thoughtless, condescending students who think her precious artifacts are “junk,” as they too have gone hunting for the same class. The unnamed narrator must prove his worth – it’s a dance. When he notices a framed portrait of the aforementioned good doctor on the floor he earns Theodosia’s graces, so she takes over the storytelling, spinning yarns. With wit and sarcasm, we gain a window into a small community’s culture appreciating their folk art that’s viewed by others as the lesser arts.

When the first story touches us in its unique storytelling and wisdom, we’re primed to love all the rest. And we do. You may be hard pressed to choose your favorite. The competition is tough.

The Mortician Confesses, story #2, was originally published in the literary magazine Granta. Narrated by a deputy sheriff, on the surface it’s ghastly: a shocking murder case like he’s never seen before. So flummoxed he repeatedly says: “Babies we all are, when it comes right down to it. We think we know decency, but we ain’t got the first idea of it, now, do we?” The crime itself is nasty, reflecting something much sadder and tragic about the rise in mental illness sweeping the country. This grim case involves the abuse of a woman with Down syndrome by someone mentally disturbed. It’s about human weakness, frailty, and loneliness, asking an existential question we struggle with: “What kind of God lets this stuff happen?”

He’s at the Office also tells a larger story echoing the heartbreak of six million Americans dealing with a parent’s Alzheimer’s disease. The grief a child feels when they watch their aging parent cognitively decline becoming a shell of who they once were. Told by the daughter of a loyal company man whose eighty-year-old dad has had to leave the job he structured his life around. Without the familiarity of his office surroundings and daily patterns, he’s more agitated and disoriented than he needs to be. An achingly beautiful tale of the lengths a family goes through to provide dignity, comfort, and peace for someone they love.

Less than twenty pages in, we realize we’re reading the story of America. Not just in the heartland and in small towns where everyone knows your business, but everywhere. About the impact of the loss of corporate loyalty to long-timers. How technology has dramatically changed lives. And what it means to reach retirement without the means for long-term care. Gurganus’ ability to wrap so much up in the telling is simply marvelous. This story, along with the final one, My Heart is a Snake Farm, also appeared in the New Yorker.

The wacky, tacky snake farm tourist attraction isn’t located in North Carolina but Florida. The snakes are actually alligators – too many to imagine – but it’s a vintage “roadside attraction.” So is the rambling motel across the road, acquired by a sixty-six-year-old librarian who moved to the state where a majority of American retirees move to if they go anywhere. The poignancy of her tale is how after six+ decades and even when her new home isn’t a dreamy situation, she feels appreciated for the first time in her life, making real friends through the kindness of strangers. Reflecting another phenomenon sweeping America: isolation and loneliness. It’s not the only story that will bring watery eyes, but it’s one of them.

The one that guarantees tears is perfectly titled Fetch, particularly if you’re one of 50 million American households who own a dog. The dog fetching is a “fat black” Lab. The narrator an observer whose voice tracks what happens when, “Something is thrown. We retrieve it, without quite knowing why.” The observer is our eyes, ears, and heart initially speculating on why the owners are walking along a rocky beach in Maine the day after a powerful “nor’easter” storm, and then making observations about how the couple is feeling watching their beloved dog who’s jumped into the wild and “frigid Atlantic as if bound for Ireland.” The observer captures the “panic” precisely the way we’d feel in the same situation.

If you’re counting, you know there’s four more stories: Unassisted Human Flight; Fool for Christmas; The Deluxe $19.95 Walking Tour of Historic Falls (NC) – Light Lunch Inclusive; and Fourteen Feet of Water in My House. They span miracles; truth in journalism; homesickness and homelessness; the golden era of shopping malls; racism, war, politics; and the “privilege of at least trying to rescue each other.”

What more could you ask of any collection? And one that’s under 240 pages?

Lorraine