Poetry in Art and Prose (Pennsylvania, Toronto, upstate New York, European cities; 1854 to 1921): I loved everything about this beautiful book that encourages us not to lose sight of our gifts.

“I’m a viewer captivated by a painted voice,” says Molly Peacock who spent ten-years studying and rediscovering a pioneering 19th century female American-Canadian artist she felt connected to. Flower Diary: In Which Mary Hiester Reid Paints, Travels, Marries & Opens a Door is gorgeously written, illustrated, and groundbreaking as no one has written a biography on Mary Hiester Reid – MHR as she signed her work.

“We don’t always need words to convey the vitality of a life. An image can do the work,” Molly Peacock says and proves. Although MHR left behind 300 still life paintings of flowers (“objects and emotions”) and later landscapes when the women’s suffrage movement emerged, she essentially left no written diaries. Which is why she was warned against writing the book.

Over 400 pages, Peacock demonstrates she’s not afraid of creative challenges and found plenty to write about. “Why try only one thing?” she asks on her artistically pleasing website. True to her words, she also answers by describing herself as a poet (see https://poets.org/poet/molly-peacock for her poetry collections, books, leadership), art biographer, memoirist, “art activist” (co-founder of Poetry in Motion on NYC subways and buses), “student of creativity,” and “word person.”

True to her words, her new female artist biography (follows Paper Garden: An Artist Begins her Life’s Work at 72) is not just one thing. It immerses our literary, visual, creative, emotional, and feminist senses.

You may never have heard of MHR but when Peacock calls her “a foremother of Georgia O’Keefe” she gets our attention. As does her marvelous poetic voice.

To give you a sense of the art infused in the book, below are three color reproductions. Printed on thick glossy paper, the Canadian publisher known for not publishing just one thing is supported by the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

True to her words, Molly Peacock segues from the main narrative to sharing parallels in her life with an artist from the past in sections titled Interludes. Printed on green-colored pages, brief as they may be (one to three pages) they move us. Most reflect on the story of her long love and marriage to “famed James Joyce Scholar” Michael Groden, distinguished university professor emeritus at Western University Canada who devoted forty years of scholarship to the Irish novelist. In dedicating the book to him we know how their love story sadly ends as he passed away in 2021 after a forty-year battle with melanoma (!), the same year this book came out. The inscription doesn’t spoil the Interludes. Instead, poignantly elevates the empathy theme.

Genre-wise, Flower Diary also encompasses art history spanning the Aesthetic movement, Impressionism, and the Arts and Crafts movement. As art criticism, Peacock’s descriptions of Mary’s flowers as “sensuous billowing roses,” “negligee-soft” petals, “the ache of tones,” “dreamy, psychological flowers” that are “constrained and free” open our eyes to an art form that conveys more than we may have thought. Against dark backgrounds, the shades or tones of the pink, yellow, and orange flowers jump off the page as the light catches them. The book also documents the importance of fellowship and friendships with other women artists when a culture prescribes how they should live their lives. How art connects, not just then but now. Aesthetically, MHR’s style is referred to as both Tonalism, “an approach that takes its impulses from music, or tones,” and Empathism as it “rarely fails to express the full range of emotions.” Collectively, a multi-layered reading experience to get lost in.

Fascinating are the connections between a 19th century female artist and a 21st century one. MHR was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, studied art in Philadelphia, made Toronto, Ontario, Canada her home, and summered in upstate New York with trailblazing artists like the legendary designer Candace Wheeler. Award-winning Peacock was born in upstate New York (Buffalo), lived in NYC and elsewhere in the US, and also made her home in Toronto, Canada. “I paced her ground.”

Another connection: author and subject are both childless. MHR not by choice, the author by choice.

However, the quality and depth of love between their two marriages is starkly different other than both spouses lifted up their wife’s art. For very different reasons.

George A. Reid was Mary’s art teacher, so she knew he’d overshadow her which he did. He became a leading Canadian painter of realistic Canadian society (economic, social, rural life), and highly influential in the establishment of Canada’s art museums. Perennially preoccupied, insensitive, and emotionally unfaithful, whereas Michael Groden is seen as wonderfully attentive, comforting, and loving. “Love is a medium, like air (like paint itself), a full, caring environment for body and for spirit,” the author who experienced that joy exclaims.

What kind of marriage did MHR have? A complicated, enigmatic one. Orphaned at a young age with her sister becoming a nun in Spain, she was “revolutionary” when she struck out on her own in Victorian society and in a marriage of two painters in which George didn’t restrict Mary’s art. He married her because of it. “Simply by painting, she affirmed what he knew was his essential self.” He a “paradoxical combination of gruff and gregarious”; she “a combination of somber and amused.” Together, a “shared core of ambition and artistry.” He left his mark loudly; she “quietly” with “gentle fortitude.”

Mary was George’s model for some of his paintings. There’s a disturbing one in the book where he paints her holding an infant. Unable to bear a child, Peacock explores whether she felt stigmatized like the era did? What about their physicality? Married thirty-six years, was it ever sensuous like their art? Below (not included in the book) George paints a lighter touch and appreciation for Mary:

via Wikimedia Commons

While we can’t begin to imagine how Peacock finished the book while Michael Groden’s life was nearing the end, at one low point she looks to her subject’s “inner strength” to lift her up. “Internal stamina that must connect to a conviction that something inside of you will perish if you don’t protect your gift.”

How and when do you know what your purpose in life is? That you have a special gift that you must protect or you will perish?

If you’re still wondering why we should care about MHR, this Canadian broadcast contributes to answering that:

MHR and Peacock also love to travel. Mary going to greater lengths to do so, “crossing oceans five times,” finding inspiration and escape in Paris, London, Madrid, and Venice. Creativity and belongingness is also cultivated in the Catskill Mountains of New York where Mary found kinship and George a new calling: architecture.

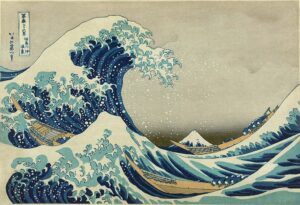

Intriguing is Mary’s painting some of the vessels she strategically arranged her flowers in with Asian motifs, inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e prints. “The Japanese word ukiyo conveys the notion of the fleeting nature of life.” An iconic floating one is The Great Wave by Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, who influenced James Whistler (also Van Gogh) who influenced MHR.

Mary also painted the interior of her homes, where she managed to carve out a space for her studio evoking Virginia Woolf’s a woman-needs-a-space-of-her-own. “Almost impossible-to-balance” as she juggled many roles. She too, not just one thing.

Lorraine