America’s fur trappers and early Western explorers (Territories west of St. Louis, from the Great Plains to the Pacific Northwest, 1826 -1829): Passions run hot about America’s West, but imagine being captivated by fur trappers, early 19th-century explorers. You will be after reading Into the Savage Country. These so-called mountain men, hunted, preserved, traded, and blazed our “magnificent country. Fertile and beautiful and savage and the whole world thirsting after it.”

America’s fur trappers and early Western explorers (Territories west of St. Louis, from the Great Plains to the Pacific Northwest, 1826 -1829): Passions run hot about America’s West, but imagine being captivated by fur trappers, early 19th-century explorers. You will be after reading Into the Savage Country. These so-called mountain men, hunted, preserved, traded, and blazed our “magnificent country. Fertile and beautiful and savage and the whole world thirsting after it.”

Told through the personal narrative of William Wyeth, looking back on three glorious, reckless years when he left St. Louis at age 22 to join a fur trapping brigade that headed 1500 miles up the Missouri River, a “soul-crushing” journey reminiscent of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Those famous explorers were backed by a President; Wyeth’s companions had only the backings of themselves, stirred by an “unquenchable desire for accomplishment, for recognition, for glory.” Muscular storytelling, as good as it gets.

Taking us inside his yearnings, motivations, and fears, Wyeth’s memories are of the “world’s great heart beating inside me.” Fresh and action-packed because his account comes from a diary he kept at the time using a quill pen, written in “parchment notebooks with velum covers.” Since the real mountain men kept journals, fictional Wyeth’s tales feel authentic.

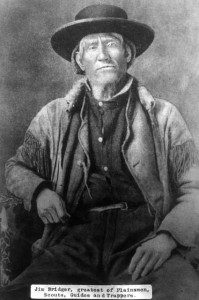

Jim Bridger, Mountain Man

via Wikimedia Commons

Lest you assume trapping beavers in the years before they quickly became depleted, or hunting buffalo along rivers, sagebrush, and mountains before the days of cowboys is not the romanticized Western you’re nostalgic for, I invite you to hold the handsome book, with its majestic Mountain Landscape with Indians painting on the cover, and finger thicker pages than most. Its sturdiness portends the adventurers you’re about to meet. Many are legendary explorers who display the same unwritten code of honor Hollywood captured: fairness, justice, courage, survival, patriotism.

You’ll also like the author’s conciseness given the incredible volume of resources on early American fur trading: journals, letters, biographies, research. There’s even a Museum of the Mountain Man, which publishes the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal to “further the knowledge base and discussion of the Rocky Mountain fur trade era.” Precisely what Burke’s novel does for us.

Structured in chapters that read like installments – The Voyage Out, The Settlement, The Far West – the reader is drawn into a time nearly two centuries ago when men were willing to sacrifice their lives for excitement, riches, or to prove something.

The prose flows. Wyeth’s self-deprecating voice is full of youthful restlessness and longing, for beautiful western mountains and a woman he falls for by page four. He feels “at the cusp of a great mystery, infinite, overwhelming, and bewildering.” Indeed, as Wyeth tells us in the opening paragraph, America is at the cusp of a new frontier:

“I was twenty-two years old and feverish with the exploits of Smith and Ashley. I followed their accounts in the Gazette and the Intelligencer and calculated their returns and dreamed of their expeditions. The fur trade was warring and commerce and exploration, and above all else in my mind, it was adventure.”

Wyeth’s trapping lands are the most pristine west of Missouri. These mountain men opened up Western territories, defined by the Treaty of 1818, which left huge swaths of gorgeous country open. Sought after by the British and of course Americans, these lands were also inhabited by Canadians, French, Spanish traders and many Native American nations: Crow, Sioux, Blackfoot, Gros Venture, Mandan. Wyeth’s adventures span what’s today the States of Montana, North and South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Wyoming. Gigantic wilderness where those “gigantic, lumbering beasts” – buffalo – once roamed.

An eye-opening Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit soon-to-close showcases the striking art of the nomadic Great Plains Indian hunters. One reason its garnered rave reviews is their sophisticated artistry was not well-known. On display are painted buffalo hide robes, fur-lined leggings, feathered peace pipes, like the wardrobe and ornamentation visualized in the novel. It too delivers an eye-opener: to a “glorious life that flamed up for a time in the Western mountains.” While there were also “darker moments” – hardships, violence, isolation – Wyeth chooses to downplay these.

He also doesn’t want to bog us down with too many “particulars of the trade.” So I’ll take his lead and not even attempt to describe the “art of fur trading,” except to say you do get a great sense of the particulars from the fur trader’s language: booseway, calumet, castoreum, pommel, cudgel, pemmican, willow trap, hivernant, palavering.

Instead, here’s particulars about a few of the characters:

WYETH: Charms us with his boyish shyness and honesty (“puffed up with self-importance”). Aware he’s different from his farming brothers, he craves “vast, wild spaces.” He fears he’s no match for these “real outdoorsmen, mountain men,” but you’ll see he proves his mettle time and time again: battling hostile tribes, a moose, a grizzly bear, and displaying exceptional horsemanship when the stakes are so high the weight of Western boundary-making seemed to rest on his shoulders. His instant infatuation with Alene Chevalier endures throughout, from their first meeting in St. Louis and then later, fortuitously, when he’s a trader with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. She’s “French with a quarter native blood that showed in her hair and eyes” … all very proper and European in her manners … she trod that middle ground between warmth and propriety.” He courts her as best he can, but she’s a widow in a long mourning who also understands the trapper’s life is exciting for the men but not for the women left behind.

Encampment, by Alfred Jacob Miller

Walters Art Museum

FERRIS: Wyeth admits misjudging Ferris, who joined the brigade at 19. The son of a physician, he seems “small and frail and boneless as a doll,” but his gentleness turns out to be virtuous good-naturedness and a natural confidence in the wilds. What endears us to him is his immense curiosity in everything around him, sketching and painting the scenes Wyeth recorded. They make an interesting pair, and become friends. Named the “White Indian,” for his genuine desire to understand the customs, adornments, and traits of Native Americans, so refreshing given our painful history of negative stereotyping. Burke introduces two famous native chieftains – Long Hair of the Mountain Crow and Red Elk of the Blackfoot – who despite their “excessive pride” are willing to negotiate and seek help. Ferris is likely to also be a real historical figure. Burke acknowledges some that inspired him, but we’re left to imagine who Ferris might be. John Mix Stanley painted the cover, but my guess is Ferris is fashioned from fur trader and painter Alfred Jacob Miller, who sketched and painted hundreds of scenes of Native Americans, mountain men, and grand landscapes. One he’s celebrated for is of Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains, depicted in the novel.

HENRY LAYTON: He’s a charismatic, energetic, boastful womanizing con man from St. Louis who knows nothing about fur trading, but knows how to put together a fine brigade. Led by Jedediah Smith, a real mountain man who like Wyeth set out at 22 to trap beaver under General Ashley, and to this day enjoys a following for having explored more untapped wilderness than any other (www.jedediahsmithsociety.org). Layton has an inconsistent personality of spirited highs and irritating lows. You, like Wyeth, will come to admire his dauntlessness for defending our territories against the British, and just about anything else that stands in the way of making the fortunes he boisterously promised his men.

Who remembers these fur trading explorers from history class? The best of historical fiction is a history light bulb. Entertaining, enlightening – and memorable.

Lorraine