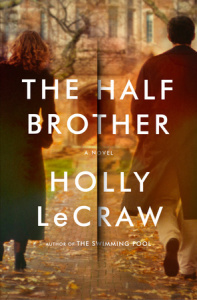

AMHERST’S author likes making connections, so let me suggest one: His thoughtful new novel is an ideal accompaniment to THE HALF BROTHER, my last posting: roughly the same New England locale; also set on a bucolic college campus; and both use poetry to explore provocative themes of love. Though, poetry – Emily Dickinson’s – looms much larger here.

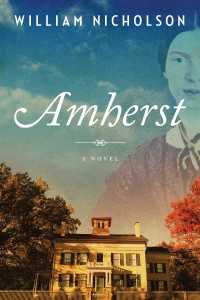

Seeking the meaning of love through Emily Dickinson’s poetry (Amherst, Massachusetts, 1880s/2012): Discovering a new author is exciting! In this case, it’s William Nicholson, an award-winning British writer of screenplays, BBC television shows, novels (six contemporary ones with characters apparently connected to AMHERST) – whose writing experiences have skilled him in honing sharp prose that’s as irresistible, mysterious, and plaintive as the characters that inhabit this novel of two connected love affairs. You’ll be hooked right by the opening sentences:

Seeking the meaning of love through Emily Dickinson’s poetry (Amherst, Massachusetts, 1880s/2012): Discovering a new author is exciting! In this case, it’s William Nicholson, an award-winning British writer of screenplays, BBC television shows, novels (six contemporary ones with characters apparently connected to AMHERST) – whose writing experiences have skilled him in honing sharp prose that’s as irresistible, mysterious, and plaintive as the characters that inhabit this novel of two connected love affairs. You’ll be hooked right by the opening sentences:

“The screen is black. The sound of a pen nib scratching on paper, the sound amplified, echoing in the dark room. A soft light flickers, revealing ink tracking over paper. Follow the forming letters to read:

I’ve none to tell me to but thee.

The area of light expands. A small maplewood desk, on which the paper lies. A hand holding the pen.

My hand, my pen, my words. My gift of love, ungiven.”

That’s Emily Dickinson’s voice, echoed in several short chapters evoking the “MYTH.” These brief interludes are in tune with the reclusive poet (by now cloistered at her home, Homestead, for fifteen years), summoning the enigmatic poet who continues to captivate legions. It’s a clue that Emily Dickinson’s poetry – and the “ghost of Emily Dickinson” – infuses this novel. As it should. For although the central voice is Alice Dickinson’s – of no kinship to the poet, again hinting at the author’s preference for connectedness – it’s Emily and her “strange poems” that casts the hypnotic spell.

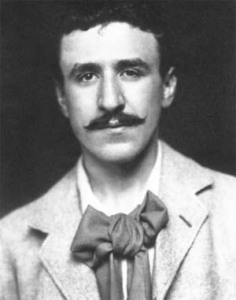

Alice has come to Amherst from England to “give dignity” to a screenplay she aspires to write about an intense, historical love in a puritanical society: between Emily’s brother, Austin, a lonely soul in a bereft marriage who finds his soulmate late in life, and twenty-something Mabel Loomis Todd, newly arrived at Amherst College from Washington, DC, married to Austin’s colleague.

Amherst College Main Quad

By David Emmerman (PicasaWeb)

[CC BY 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Another reason for Emily Dickinson’s popularity: “words and phrases exhibiting an extraordinary vividness of descriptive and imaginative power, yet often set in a seemingly whimsical or even rugged frame.” Her poems were a radical departure, hence underappreciated early on. Contributing to their elusiveness are features such as the omission of all punctuation except for dashes; most lack titles; capitalizing words mid-sentence; rhythms that don’t rhyme. There’s also the sheer breadth of themes beyond ordinary existence – nature, biblical, spiritual, death, immortality. Like the Puritans of her day, she valued a simple life but she also defied accepted beliefs and customs, trusting her own individuality as the highest power. Thus, she feels all-knowing and timeless.

Mabel Loomis Todd became obsessed with Emily’s poetry (and wanting to meet her). She sensed a powerful connection to this spirited woman who expressed emotions she felt for the “greatness, mystery, and depth of life.” Her father, dear to her, introduced her to poetry, but it’s her dismay at the sleepy college coupled with her hunger for adventure and true happiness that sparked a ‘perfect storm’ for escaping into and idolizing Emily Dickinson’s poetry. History ought to be indebted to Todd for her adoration, devotion, persistence and painstaking role, as depicted in the novel, in transcribing and getting a selection of Emily Dickinson’s poems initially published. The evolution of Mabel’s determination is seductive storytelling.Mabel and Austin’s fated affair began innocently over a mutual love of nature. The “joy of understanding” touched their souls. Togetherness and physical love blossomed very slowly, discreetly, given the morality of the era, heightened by Austin’s sensibilities and morose acceptance of his unhappy destiny. Eventually, though, their ardor finds its way into the privacy of Emily’s home, where you can feel Emily lurking as the lovers rendezvous in her living room. (Emily doesn’t live in total isolation; there’s her spinster sister, Lavinia). Austin’s home, Evergreens, is conveniently connected to Emily’s. You can, like Alice, pay a visit: it’s the yellow home illustrated on Amherst’s telltale cover, now the Emily Dickinson Museum, which appears to be beautifully preserved. It’s a testament to Nicholson’s writing that the reader wishes to visit there too.

Unlike Emily, Mabel is beautiful, stylish, aglow; she craves attention and attracts it from everyone. Whereas Austin must hide his feelings from his cold, begrudging wife, Susan, Mabel is remarkably open with her unjealous husband about hers, for he’s candid about his extramarital desires. David believes, even goes so far as encourages, the idea that loving more than one person at a time grows one’s capacity to love: “The more you love, the more love there is.”

The novel, like Emily Dickinson’s poems, respects a broad spectrum of types of love: romantic love, familial love, self-love, spiritual love, love of nature and the arts, enduring love. It also raises connections among some. For instance: Does a love for a father figure influence who you choose to love? Nicholson makes sure you think hard about that question by structuring his novel with two love affairs, historical and contemporary, that draw interesting parallels:

Mabel Loomis Todd is in her mid-twenties when she falls deeply in love with a man old enough to be her father. Alice is also in her twenties. Her Dickinsonian research re-connects her to her former boyfriend, Jack, whose mother had an affair with Nick Crocker, a visiting English professor at Amherst. Jack, in turn, connects Alice to Nick. Alice is searching for a happy ending to her play because she too longs for the greatness of love. Nick, like Austin, is also in his fifties. He’s exceptionally handsome; all the women find him “irresistible.” He lives in a “grand wedding cake of a house,” and like Austin is unhappily married. An “old soul,” who can recite Emily’s poems. Need I say more?

As Nicholson weaves in Mabel and Austin’s soul-searching letters and Emily’s heady poetry – “the lovers act, the poet reflects” – offering his own reflections, often punctuating a character’s crisp dialogue with their inner thoughts, he lets the reader in on what we’ve already been thinking: “How complicated it all is,” and “We all live our lives in hiding.”

When Nicholson asks us to ponder “What is there that’s bigger than love?” is the answer Alice’s happy ending? A cache of nineteenth-century stirring letters and poems may hold the key: A love so profound it resides deep within one’s soul, blessed forever. Until eternity.

Lorraine