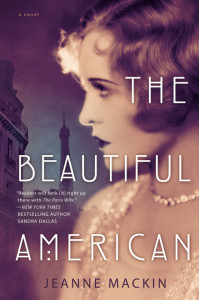

Without meaning to, The Beautiful American nicely follows Madame Picasso, my last posting. Picasso’s back, a minor role yet a profound one. Instead of Cubism as the new art form, here it’s photography and Surrealism. Historically, the reader is swept past the “anything goes” pre-war Paris years into occupied and post WWII France. I thank my lucky stars for having a way to share this gem.

A Perfumer’s Story and a Photographer’s Story: The friendship of imaginary Nora Tours and the real Lee Miller (Poughkeepsie, NY, London, Paris, Grasse, Cannes, 1914 to 1977): The Beautiful American is beautifully structured, beautifully told. You may wish the true beauty to be fictional Nora, for her quiet strength, but the singular title is meant for the wilder Lee Miller, famous war and fashion photographer, Vogue model, and muse/lover of the surrealist photographer, Man Ray. For it is Lee Miller Jeanne Mackin “wanted to learn about … and I thought others would find her fascinating as well.” She’s certainly that!

A Perfumer’s Story and a Photographer’s Story: The friendship of imaginary Nora Tours and the real Lee Miller (Poughkeepsie, NY, London, Paris, Grasse, Cannes, 1914 to 1977): The Beautiful American is beautifully structured, beautifully told. You may wish the true beauty to be fictional Nora, for her quiet strength, but the singular title is meant for the wilder Lee Miller, famous war and fashion photographer, Vogue model, and muse/lover of the surrealist photographer, Man Ray. For it is Lee Miller Jeanne Mackin “wanted to learn about … and I thought others would find her fascinating as well.” She’s certainly that!

Our lens for learning about Lee Miller is seen through the softer eyes of the imagined narrator, Nora Tours. These very different women, unlikely friends, come together at important “thresholds” in Nora’s life. Their seventy years are creatively divvied up using names borrowed from the world of perfumery – for Nora has inherited a “good nose” and at various times in her story she sells perfumes. The Prologue is titled Départ; Part One is Note De Tête; Part Two is Note De Coeur; Part Three are the Base Notes; and the Epilogue is the Sillage. Their essence:

Prologue: “Begins the journey of perfume and its wearer”

Part One: The “top note.” The ‘once upon a time’ opening”

Part Two: The “middle notes suggest the destiny”

Part Three: The “base notes,” which have the “most lasting impression”

Epilogue: The “closest thing to a molecular memory.” The “final lasting impressions.”

These descriptions come from perfumery notebooks composed by Nora. The artfulness of composing runs throughout: Nora composed perfumes, Lee Miller and Man Ray composed photographs, and Jeanne Mackin has composed a wonderfully enlightening historical novel filled with a range of human emotions: love, loyalty, betrayal, melancholy, anger, jealousy, grief, regret, forgiveness.

Perfumery and Photography shape Nora’s and Lee’s stories and the wistful prose. Just as perfumes are “memories pressed into memories” and photography captures memories, the novel looks back at Nora’s memories so she can reveal to us the circumstances that led her teenage daughter, Dahlia, to disappear. From the opening pages, we’re told Nora is frantically searching for her. Lest you assume Dahlia has run away from a bad mother, think again. If Dahlia “wanted the moon,” Nora “would pull it down for her.”

The “once upon a time” part of the story is how Nora and Lee, both born in 1907, became early childhood playmates despite differences in social class. Nora’s father was the gardener at Lee’s upstate NY family farm, where he infused Nora with the nostalgic flower and herb scents passed down from his great-great grandfather, a perfumer in France. Lee’s father, Theodore, was wealthy and indulgent. Something tragic happened to Lee, a “vulnerable beauty” by 7, ending their friendship. A closely-guarded traumatic event, which enormously influenced Lee. So private that Nora, who knew about it, pretended not to when she and Lee bump into each other years later at a bookstore and Lee doesn’t even remember the gardener’s daughter; and then later, far more significantly, when their friendship and the novel heats up, in Paris, in the late ‘20s, when they meet again.

Nora was 20 when she “danced across the Atlantic” with a boy she deeply loved, her high school sweetheart Jamie, the “Tastes-So-Good” baker’s son, an aspiring photographer hoping to be discovered. Her devotion to him is boundless. Their stay in London was brief; Paris, the “center of the world,” seven years. It’s during these pre-war Paris years, when Nora runs into Lee again, now a Vogue model discovered by Conde Nast. She’s also the muse of the avante-garde photographer, Man Ray, 20 years her elder. Their relationship is as edgy as their art. His is a possessive, “aching, can’t-live-without-her love;” hers “nuanced,” anything but conventional. For Lee Miller is a restless soul, dauntless, seductive, fiery. Things don’t seem to bother Lee the way they do Nora, like Man Ray’s cut-up images of her – a “single eye representing the entire body of the woman he adored.” Nora sees violence in these nightmarish images, a “touch of cruelty in the worship of beauty … Wasn’t the most beautiful woman in the world that armless, defenseless Venus de Milo?” But Jamie is infatuated with Man Ray’s artistry.

Man Ray, then, is also a transformational figure for Jamie, who gradually grows consumed by ambition. Although Lee, “like many artists, could be on the self-absorbed side,” she cannot be pigeon-holed. She helps Jamie land a position as assistant in Man Ray’s studio. So does Picasso, one of Lee’s many legendary friends. But Jamie struggles. His “lovely and natural” photographs of “real people” are not hot. The ever-steady Nora tries to assuage Jamie by reminding him that timing is everything in the art world, things will change. They don’t for Jamie, which has heavy consequences for Nora, forcing her to flee Paris in 1932.

Interestingly, it’s Picasso who comes to her rescue because it’s Picasso, the shrewd businessman, who stays in touch with his past patrons (a way to manage sales and his reputation), so he knows of the Grasse home of a widow, Madame Natalie Hughes, willing to take Nora in. Her son, Nicky, also a widower, bought some of Picasso’s early works for his hotel in Lyon. This is serendipity for Nora, Grasse being the “perfume capital of France.” Madame and Nora find solace and contentment in each other, both outsiders and survivors.

While the author’s descriptions of Grasse sound lovely – lavender hills, jasmine farms, olive orchards, stone houses covered by moss and colored by red geraniums – Grasse is somber compared to Paris. It is here that Nora must fashion a new life not only for herself but her baby daughter, Dahlia. The reader can guess who the father might be. Madame Hughes, Nora, and Dahlia become a little family. Village life is peaceful, until war rages.

Without giving away what happens next, this part of Nora’s story illuminates how divided a country France was during and after the war. Two and half million French fought the Germans, supporters of De Gaulle’s Free French, as well as the French resistance fighters. But the Vichy government fed right-wing sympathizers of Hitler.

Post WWII France is anything but normal too. This is when Dahlia runs away, and Nora begins her desperate search. Retracing her London days, she chances upon Lee again, by now a famous war photographer and married to the art collector, Roland Penrose.

It’s at this point that the novel comes full circle: final chapters re-connect with the introductory one. Events, though, have dramatically changed these women. Lee’s not as beautiful as she once was, having seen the horrors of war behind her camera. And Nora is now the one with the closely-held secret.

To tell a lifetime of stories, Nora has us looking backward and forward. “Home is always in front of us or just behind us, except for the home we carry inside that is more than mere place.” It’s this home, Nora’s soul, which we keenly sense. It leaves a lasting impression.

Lorraine