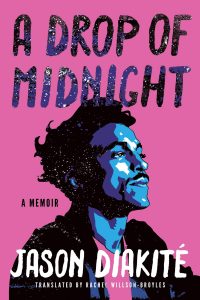

Soul-searching – a hip-hop artist’s journey to come to terms with his multiracial identity (from Sweden to American roots, 2015 – 2016; epilogue 2019): A stanza from Maya Angelou’s powerful poem, And Still I Rise, sets the piercing message and lyrical tone of A Drop of Midnight, Jason Diakité’s stunning memoir that should be essential reading on black history.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

An international hip-hop star, the author is known professionally as Timbuktu. So expect to be treated to an illuminating discussion on hip-hop music and culture originating from the “ghetto streets” of Harlem, Bronx, and Brooklyn, New York to its spread world-wide – instrumental to Diakité’s rise above an “identity crisis” he’s struggled with much of his life.

For decades, Diakité sought to overcome all the pain, shame, loneliness he’s felt about his light brown skin color. With a father who is black and a mother who is white, he was caught up in a turbulent state of “in-between-ness.” To better understand his feelings, himself, he sought to better understand his family’s history. So also expect a thoughtful, sweeping yet distilled examination of African American history, and a realization that his music and his history are entwined.

“Who am I? Who are my people? Where is my home?” are the overriding questions. Many, many more are achingly asked to embrace the black and white worlds Diakité straddles.

Born in Sweden to parents and ancestors from Nigeria, Harlem, the Deep South, Native America, and elsewhere, he explains:

“I have a complex system of roots that branches across continents, ethnicities, classes, colors, and eras . . . I am all the countries my forefathers came from and were shipped to in chains. I am all the colors and shades of their skin. I am their rage and their longing, their hardships, successes, and dreams. I am the intersection, of Slovakia, Germany, France, South Carolina. Of white, black, and Cherokee.”

His parents met, married, and lived in Harlem, then moved to Sweden to escape racism; divorced, they remain amicable. The three live in different Swedish cities: Diakité in Stockholm, his father – who prefers his African name Madubuko – in Malmö, his mother Elaine in Lund.

Despite his father’s achievements (a documentary filmmaker and human rights lawyer), he’s carried the heavy weight of “poverty and misery.” His mother is from an entirely different background: her family made their money coal-mining in Pennsylvania. Striking how “ashamed” she felt being white once she met Madubuko, while their son was ashamed his skin was not.

At forty, Diakité looks back to when he was conscious of his skin color, at eight. His middle school years were marked by relentless bullying – “pigmentocracy” – that “colonized my soul and trickled out back like a poison.” “Where do young kids learn so much soul-crushing hate?”

His parents chose Scandinavia for its human rights legacy until immigration changed that. First they moved to Copenhagen, where his father planned to attend film school, moved when he learned education was free in Sweden. A great believer in “education and the dignity it gives you,” advice his well-read son took to heart. Literature, especially the works of “black intellectuals,” informed Diakité’s identity development. Black writers like W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Angela Davis, Eldridge Cleaver, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Zora Nelson Hurston, Cornell West, and more. Inspiring, for all who believe in the power of literature.

Dignity is what rises above “grinding poverty.” “In our day, his father says, “dignity was important. You didn’t want to look poor. We may have been poor in a financial sense, but spiritually we weren’t.” A proud man, adamant against his son writing this memoir. Eventually, he consents.

Written on a chronological identity path, but mixed with difficult conversations back and forth over time with his father, probing questions with his mother too. There’s other voices – relatives, friends, artists, activists – but it’s Diakité’s literary voice and courage to dig deeply that makes the memoir sing. Even when the songs are painful to hear.

Dignity is what’s shown in the revealing opening line about Diakité’s dignified grandfather, Solomon Warren Robinson, nicknamed Silas, whose “shoes were always shined.” A Drop of Midnight always shines too, even when ugly truths are told and anger roars in profanity in dialogue, forcing us to listen to what’s really being expressed.

Silas, who proudly “never missed a day of work,” is the first reference to black history. A waiter on a dining car on the long-distance trains of the Pullman Company launched after the Civil War (lasted until the ‘60s). The company was notorious for hiring black waiters and porters who toiled long-hours in low-paying jobs. But historians claim this gave rise to a black middle class and the civil rights movement.

The author possesses and cherishes Silas’ threadbare coat “woven of the same cotton” he and his parents picked in Allendale, South Carolina. It’s the first stop on Diakité’s physical journey to America in 2015, alone. What he finds is unbearably depressing poverty. Another family place he visits is Harlem, also “born of misery” but it’s also the birthplace of hip-hop music:

“Infectiously captivating and full of such bold emotions that they permeated everything else – contemporary music, fashion, art, the way people talk, the way people walk, the way people are.”

Infectiously captivating perfectly describes this book.

After twenty years of devoting his life to music, which gave the artist a positive sense of self but ended his marriage like his parents,’ he finds himself at a crossroads, asking: “What should I do with the rest of my years”?

To answer that, he’s compelled to investigate his family’s history that’s instructive to him, and us. Activism common among them. One character looms large: his hardened paternal grandmother Madame, an advocate for “Pan Africanism,” which sought to unify the dispersed peoples of Africa.

Madubuko’s storytelling is the loudest and key to Diakité understanding himself. A witness to the explosive sixties, history we must never forget – when MLK, Malcolm X, and JFK, a champion of civil rights, were all taken from us, while the KKK did its destruction in the Deep South.

There’s also history and stories that lift us up. Music, of course, chief among them. Like the time the author discovered hip-hop music in the ‘80s sitting in a Swedish theater watching a bouncy film made on the streets of New York, Beat Street.

And the time Diakité’s father brought him his first hip-hop record, Break Dance Party. Performed by a group named Break Machine, it became his break into breakdancing, camaraderie, and affirmation. “Rap music radiates an attitude of you may trample us down, but you can never shut us up.”

Music is healing. Music connects Diakité with his father’s dear Swedish friend, Don, when they all get together and music plays. Though, jazz, blues, and hip-hop always go back to “slaves’ songs.”

Besides Harlem and the Deep South, Diakité also visits Baltimore to see his Uncle Obedike. A symbol of rampant, racially motivated gun violence, he was a police officer shot during the city’s ”race riots” in 2015 that erupted over the cruel death of Freddie Gray.

“How can people live with shutting out the truth generation after generation?” Diakité asks. Seems he’s found his own answer to this question and to what comes next. By sharing his lessons to finding inner peace, he’s become an advocate for global peace through diversity.

Lorraine

A love of reading is a gift, especially during these social distancing times.

Pingback: A Single Swallow ← Enchanted Prose