Dissecting a thirty-year marriage (Cambridge, Massachusetts; 1970’s to 2015): What do you do when you learn your husband of thirty-years has betrayed you? When you thought your marriage was the envy of others?

In the six years it took Sue Miller to write her eleventh novel about contemporary families and marriages, she’s had time to get to know Annie and Graham, the characters whose long marriage seemed so happy and contented but maybe it wasn’t. Like Miller, Annie has time for reflections, which gives her a “slowly transforming sense of him.”

That quote was taken from the author’s Dear Reader note she wrote introducing her new novel, saying, “she was struck with how the writing of” her 2001 memoir about losing her father to Alzheimer’s, The Story of My Father, had affected her perspective of him once she dissected his life. These words are instructive since she goes on to say, “that it was only years later that I began to imagine exploring that experience fictionally.” Monogamy is that story: a thoughtful, unwinding story of a thirty-year marriage marked by love and warmth but also betrayal, which over time allowed for some level of acceptance, gratitude, forgiveness, healing.

Annie is a photographer. She sees things in the moment more clearly through her camera, much like Miller who perceptively delves into the emotional feelings of her characters through the lens of her sensitive prose. Miller is not an author whose characters wrote the story for them. They’re in her head; so is the story. She writes to fill in the blanks.

While this may not sound like an original story, it’s what Miller brings to it that makes it so. Ever since she stepped onto the literary stage over thirty years ago with The Good Mother, she’s earned a reputation for her emotional understanding of her characters. I seem to recall critics calling it chic-lit. No one should be calling Monogamy anything but literary fiction. The best kind because we can easily relate to the complexity of it, which is why it’s an immensely satisfying, questioning read, if you like your novels to evolve over time.

Written in the third person, the narrator is introspective; Annie portrayed much more so than Graham until he wakes up too late to his “more or less bottomless hungry,” “greedy” self. He’s the exuberant partner, so this is a tale of opposite personalities attracted to each other.

Graham “has always been passionate about life, women, food, books, music, booze.” He’s a big man physically, and in his overwhelming presence. At one point, Annie confides to an old girlfriend, a playwright, Edith, how angry she is “that he took up all that psychic space. That he took me up.” Graham poignantly finally realizes that too. When he does, he’s overcome by a “sudden deeper remorse” that “he forgot her life, going on around his.” His confession tugs at our emotions, betwixt and between about the couple. They’re both good people, and also flawed. We admire Graham’s lust for life, but not the pain he brings to his wife who has a history of sensitivity to his needs and a willingness to let him be. And yet, she could have/should have stood up for herself somewhere along the line.

The inside flap of the novel gives away what reviewers call spoilers. It comes around a third of the way in. Suffice it to say that the rest of the novel has a sorrowful tone as Annie looks back on her memories, analyzing the man her world revolved around. Another character, Frieda, Graham’s ex-wife, who still carries a torch for him, with whom Annie has maintained a friendship with over the years that deepens with ramifications, reminds us that Annie is someone who “pondered things, she took things seriously” and is “dignified.” Which is why we feel far more empathy for Annie than Graham, but we do understand him.

Frieda and Annie not only shared a husband, but they also share a son, Lucas. He went through a difficult childhood missing his dad. Sarah, Annie and Graham’s daughter, had a lonely adolescence, too, but Sarah was in the house with her father and still missed him. You’ll like both children – one who works on her self-image, perfects her “velvety” voice and musical tastes to become a radio host; the other who followed in his dad’s book-loving footsteps, working for a book publisher. Loving books and other forms of art delight and run throughout.

Sarah and Lucas, while not meant to be afterthoughts, don’t take center stage since this is meant to be a novel about parents more consumed with themselves, with unintended consequences. They love their children, but they’ve been overlooked.

Graham’s the extrovert. He owns a bookstore in Cambridge, Massachusetts near Harvard Square. Annie met him at the gala opening. Gregarious and energetic, he loves celebrations, parties, entertaining. Annie’s reserved and private, though Graham has brought her out of her quiet shell, seen through their frequent, warm gatherings with friends, she a gracious host.

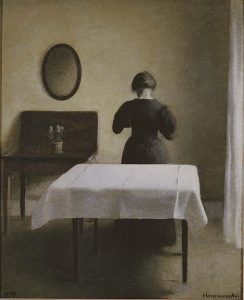

Like Miller does with Graham, she wants us to understand Annie’s character, and how much her art means to her. When the novel opens, she’s set to have a gallery show, a big deal for someone who put her art second to her marriage and yes, motherhood. By sprinkling in the names of artists Annie likes, we get a visual picture of her as a person and an artist. References include Danish painter Hammershøi; French painters Pierre Bonnard and Antoine Vuillard; and American photographers Nan Goldin and Robert Mapplethorpe, who shocked with his intimate, sexual, black-and-white pictures. The first three artists are known for their quietly intimate works of everyday things; Mapplethorpe and Goldin offer a raw side of intimacy. Annie, like Graham, like all of us, should not be stereotyped, and they’re not.

via Wikimedia

[CC BY-SA 3.0]

[CC BY-NC-SA 2.0]

Similarly, the novel is intimate and sensual. Annie and Graham enjoy a satisfying sexual life. The sensuality is also expressed in the “sense of loveliness that made everything possible,” including an appreciation of Nature.

While the timeframe is unclear, there’s enough cultural and political references to get our bearings. For instance, there’s mention of the Blue Parrot Café, which flourished in the seventies. Anyone who was in Cambridge back then, myself included, knows Miller has instilled the free spirit of a place and an era. For some, there’s an element of nostalgia going on here too. Certainly all the community at Graham’s lively bookstore — boy do we miss that in 2020! At the other end of the time spectrum, there’s mention of McCain’s presidential campaign and Obama’s second term in office, so we can estimate when the novel ends. Not specifying the precise time period adds to the novel’s universality.

When Annie’s friend Edith says, “We read fiction because it has a shape, and we feel . . . consoled.” That’s how it feels to read Monogamy.

In another insightful scene, Annie is having a conversation with an author she met when the two were writers-in-residence at the MacDowell artist colony. She asked him to describe the book he’d written. While he gave her a quick synopsis, he said, “I don’t want to tell you what I think it’s most deeply about, or what you’re supposed to think about what it’s about.” This is the same message Miller achieves.

Lorraine