Disintegration (Germany, 1938): Justly hailed by the publisher (and many others) as a “remarkable literary rediscovery,” The Passenger is remarkable in a number of ways.

First and foremost: for eighty years German-Jewish refugee Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz’s original manuscript was presumed lost like its twenty-seven-year-old author who perished during WWII, along with 361 other passengers, on a British Military Transport Ship bound for England. Released from a prison internment camp in Australia, the HMT Dunera was attacked by a German U-boat.

via Wikimedia Commons

Discovered in an archive at the National Library in Frankfurt, Germany, the chilling historical novel was published in 1939 to little fanfare and has now been given new life at a pivotal time: when the world’s largest refugee crisis is at an all-time high, and another dangerous wave of antisemitism (and other hate crimes) is also rising dramatically.

This literary discovery is also remarkable in the sense that it feels semi-autobiographical. Boschwitz’s real story escaping Nazism pulsates in his fictionalized one in which his German-Jewish protagonist, Otto Silbermann, was living in Berlin in 1938 when The Night of Broken Glass or Kristallnacht ignited, marking the start of the Holocaust. Otto’s on the run, hopping on and off trains as a passenger on the German National rail system not knowing where to go where he’ll be safe.

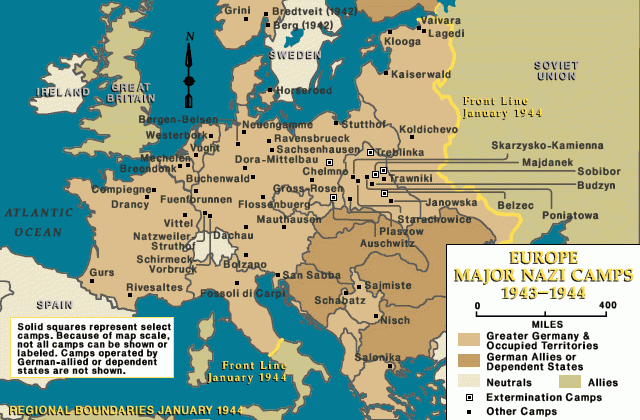

Remarkably, Boschwitz’s and Otto’s perception of what was going to happen to the Jewish people was prophetic. Acclaimed writer and Distinguished Professor of Comparative literature André Aciman tells us in his succinct, informative Preface that what Otto went through in the aftermath of Kristallnacht happened before Jews were forced to wear yellow stars that humiliated and vilified them as Jews; before millions were hauled into railroad cars like cattle to be taken to concentration camps in Germany and Poland most infamously, but by the end of WWII a numbing 980 extermination camps had spread throughout Europe.

More than any novel I’ve read recently, Otto’s psychological state – his anxieties, fears, impulsivity, vacillation, disorientation, and falling apart – are revealed through dialogue that exposes the intensity of how loathed Jews were and the trauma inflicted on one’s sense of self.

Substituting the author’s true story of seeking refuge from the Nazis traveling from country to country, Silbermann travels back and forth only within Germany booking first-class, second-class, and third-class train seats unsure where the best place to blend in is. While he tries to remain calm not to call attention to himself, that lasts only so long. Otto is an astute passenger observing and eavesdropping; sometimes desperate to talk to other passengers, including a couple of men he suspects are in a similar situation and a woman he’s ridiculously attracted to. Jumping on trains from “Berlin to Hamburg, from Hamburg back to Berlin, then from Berlin to Dortmund, Dortmund to Aachen, back to Dortmund, and eventually back to Berlin,” he’s caught up in a maze of daunting dead-ends.

Throughout, he ruminates over why he didn’t escape Germany sooner. What Otto goes through is more innermost reflective, angst-ridden, and existential rather than plot-driven. Feeling trapped and frantic, he becomes crazed like a mouse in psychological experiments in which the creature is stuck going round and round on a wheel going nowhere. Some consider Ottos’ nightmare of powerlessness and hopelessness during an extraordinarily dark period in history Kafkaesque. (Interestingly, award-winning translator Philip Boehm translated one of Franz Kafka’s books, Letters to Milena).

Business is one reason Otto didn’t leave Germany. He’s even prescient in choosing scrap metal as his profession as it was sought after during WWII. What he didn’t know for over twenty years was that his partner, Becker, was anti-Semitic, playing into the stereotype of opportunistic Jews who become wealthy. The dialogue between the two men when Becker finally releases his pent up resentment and prejudices astounds Otto, and feels so real. So does Otto’s hopeful reaction: “There still have to be people who maintain their decency and humanity no what opportunities might come their way.”

An optimistic, responsible, peaceful man, he fights to retain those qualities but as he becomes lonelier, alienated, and hysterical realizing his country would do anything to destroy him and his family to erase his identity and existence those strengths unravel.

Another reason Otto doesn’t want to leave Germany is his wife, Elfriede. When the Storm Troopers (Brownshirts) invade their home, Silbermann manages to escape yet he spends the rest of the novel anguished not knowing where his wife fled. Despite not being Jewish, her life was in danger through marriage.

What’s also remarkable is the prose: so raw and fierce because it was written within days of the Kristallnacht. Words penned feverishly over warp speed, apparently in a month’s time. This isn’t historical fiction written years or decades later; it’s coming to us, hitting us, while it was happening. While our President is warning “democracy is in peril,” a few years after The Washington Post adopted a new tagline: “Democracy Dies in Darkness.”

Silbermann’s disbelief that what was happening was in “the middle of Europe, in the 20th century!” descends into psychic despair and deterioration as he fully grasps Germany’s commitment to “the utter despoliation of one’s identity, of one’s trust in the world, and ultimately of one’s very humanity,” explains Aciman.

Otto’s son Eduard is stuck in Paris unable to get a visa at a time when a newspaper reports on “The Murder in Paris. Jews Declare War on the German People.” Germany’s grip is spreading across Europe. We feel it palpably.

Several people Otto encounters tell him he’s lucky no one “can tell by looking at you that you’re Jewish.” A stereotypical, offensive question, but even Otto thinks about this, often. In a particularly visceral scene, Otto is torn when his old business friend, Fritz Stein, wants to eat with him at a Berlin restaurant but frightened he’ll give them both away because of Fritz’s “Jewish nose.” Not looking like a stereotyped Jew is not Otto’s biggest asset. It’s his wealth, which he lugs around in a heavy suitcase thinking the money may come in handy to bribe German authorities.

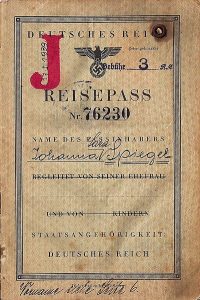

Another stereotype is Jewish surnames. Silbermann is a German Jewish name. On a train the female passenger he’s enthralled by asks him why he doesn’t change his name. He has the money to falsify documents, but he replies: “If I give a false name I’d be breaking the law. It’s terrible. The state is practically forcing one to commit an offense.” His moral compass is admirable but when it comes to survival it’s beyond irrational. Germany in the 1930s and ‘40s stamped passports with a big red J. We can’t help but wonder if they made such life-and-death pronouncements based on stereotypes since European Christians also had Jewish surnames.

Another distinguishing feature about the storytelling is its effective mix of first person narrative and dialogue, in addition to observations and commentary by a third-person narrator.

There’s one hope for Otto and it isn’t money. It’s dignity. “Dignity, he thought, a person has his dignity and that’s something you can’t let anyone take away.”

Does he keep his dignity in tack? Wouldn’t that be a remarkable outcome? The reader hopes.

Lorraine