What happens when a biracial couple escape racism in America for France in the late 19th century? (Paris and the Languedoc region; 1892 to 1937): The Pink Dress, the alluring painting on the cover of Christopher Tilghman’s new novel, was painted by French artist Frédéric Bazille just twenty years before Thomas and Beal in the Midi begins.

Thomas Bayly and Beal Terrell are characters from two of Tilghman’s earlier novels set on the Eastern shore of Maryland: Mason’s Retreat and The Right-Hand Shore. Adeptly weaving in the couple’s backstory on Thomas’ family estate and farm on the Chesapeake Bay, this novel reads as a stand-alone.

Seductively alive, the plot centers on finding “a place to call home” after two childhood friends fall in love and marry illegally since interracial marriages were banned in Maryland back then. (Shockingly, Maryland didn’t repeal the law until the late ‘60s civil rights movement.)

Thomas is twenty-one, white, and privileged; Beal is nineteen, black, and her ancestors were slaves. She and her mother were servants at Mason’s Retreat. When Thomas and Beal wed, they fled to France during the Belle Époque era, when the country was at peace and the arts flourished. The elegance of the prose; Beal’s elegance; Thomas’ dignified handling of Beal’s awakening; and the revolutionary spirit of their marriage suit the Beautiful Age.

A stark contrast to the history of slavery in the bucolic and coastal Chesapeake Bay two hours outside Washington, DC known for its world-class sailing and blue crabs. But this region was also home to slaves and activists Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass.

Christopher Tilghman grew up here too and his family’s roots also go back to the 1600s, so it’s not surprising he was deeply affected by the history and landscape, infused in his writings.

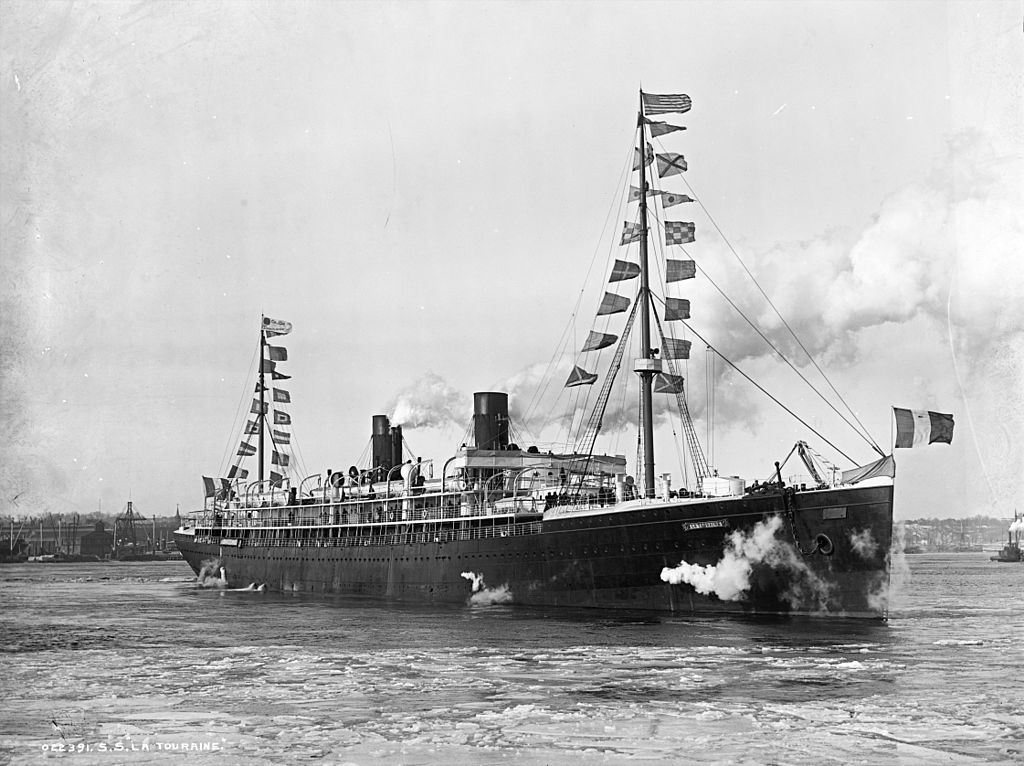

Opening with another character – Madame Lucy Bernault – summoned by Thomas’ older, “austere,” sister Mary who’d been a student of the nun, to watch over Thomas and Beal, she’s waiting in Le Havre, a major port city, to meet the young couple when they disembark from their luxury ocean liner, the SS La Touraine.

By John S. Johnston [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In the opening line, there’s a designation after Bernault’s name: RSCJ. The Catholic Society of the Sacred Heart was founded in France in the 1800s. When Thomas and Beal immigrated to France, the “Mother House” was located in Paris. Educating poor girls was (is) its mission; Hôtel Biron, the site of their boarding school, today houses the sculpture museum, Musée Rodin.

The society’s missionary boarding schools spread to many countries, but the specific reference on page one to Lucy’s Louisiana experience teaching there introduces the religious order’s disturbing connection to slavery, bridging the gap between then and today’s reparation urgings.

As Sister Lucy watches the passengers walk down the gangplank, she first sees a chained black man, a prisoner, and thinks: “In all her years in America, the horror of American slavery had never left her.” The concept and ideal of equality are a big draw. Her intentions are full of grace and love. Throughout the novel, the couple’s friendship and gratitude for all she does is heartening. Highlighted here, in addition to the slavery messaging, as an example of the impressive research the author has fleshed out into Thomas and Beal’s story of love.

The nun is the first of many characters to behold Beal’s “solid beauty.” The “delicacy of her hands and fingers.” Her “strikingly pale eyes.” How “her dark skin was absolutely flawless.” Her tall height and wide shoulders. When she also spots an “extremely tall African man,” she humorously wonders whether “everyone in this story is a giant?” Indeed, this is a giant tale but that’s not the question she would have asked had she been on the ship and seen how the well-dressed, well-spoken, domineering man eyed Beal.

Monsieur Diallo Touré is from Senegal, “where our people are rising” he tells Beal. A diplomat in the French National Assembly, part of France’s Parliament, he gets under Beal’s skin for the arrogant assumptions he makes about her white husband. Like so much that goes through Beal’s mind, she keeps this incident secret, assuming this will be the last she’ll see of this charismatic man. But it’s not.

On page 39 of this nearly 400-page novel, Sister Lucy utters prescient words that drive Beal’s coming-of-age story:

“Your love will be tested; otherwise, how will you ever know its depths? None of us knows what lies ahead of us. But you are brave and in love, and perhaps that’s all you will need in the end.”

Beal’s eyes are just beginning to open in a city famous for doing that. She loves the fashions that suit her elegance and beauty; early on befriends two women artists who are copyists at the Louvre, so she spends time there observing and recording her thoughts in a journal – Thomas’ idea to help her grow, also helping her fit right in the Latin Quarter where Lucy found their apartment and where artists and writers hang out.

Initially, Beal wants nothing to do with the American artists, but they’re a persistent bunch. Interestingly, during artist Bazille’s early years he hung out with pioneering artists there that led to Impressionism.

How did Tilghman find such a perfect image for his novel? Did he see the painting at the Musée d’Orsay, where it hangs?

Racism in Paris isn’t seen. The artists Beal encounters see the beauty of her “coloring,” not that she’s “colored.” Would she have been treated differently if she wasn’t beautiful?

Tilghman’s evocative and atmospheric storytelling feels old-school in the sense that he takes his time to tell it in long-flowing, often flowery prose.

Beal’s beauty is both a blessing and a curse, testing her. Male artists crave drawing and painting her; two compete for her as their muse. One is a Jewish man, Arthur Kravitz, who’s moody and angry, reminding us this was the time when the Dreyfus scandal consumed France. Again, Tighlman finds a way to bring dark history about human rights into his love story.

Do you believe there can only be one “true love, in life and literature”? The novel asks us to consider this question as both Beal and Thomas become conflicted. Thomas’s adoration and love translates into quiet patience as he wants Beal to figure out who she is and what she wants, aware she hasn’t tasted life and freedom to understand the depths of love Sister Lucy spoke of.

Meanwhile, he experiences a different type of attraction, also quiet about it, meeting and befriending a very helpful Irish bookseller, Eileen, in a Paris bookstore with a comprehensive collection of English-language books on French industries. Spending his days there, Eileen’s assistance is pivotal, sparking the second part of the novel set in the Midi: a cultural geographic region in the south of France bordering Spain, where the language spoken is called Occitan.

By Keg1036, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

With roughly 100 pages remaining, the author reveals a spoiler about the fate of Thomas and Beal in the Languedoc. I don’t intend to do that, perhaps my only quip with this thoughtful novel. Suffice it to say it shows the impact of Thomas’ kinship with his Chesapeake heritage.

The novel reflects the same effect on the author, also an English professor and Director of the University of Virginia’s Creative Writing Program. Tilghman acknowledges the resources he used to inform this gorgeous novel. No surprise it took years to craft.

Lorraine